A refreshingly positive anthology of personal accounts edited by Shinie Antony and AT Boyle, links personal loss with intangible objects readers, and the process of letting go

The mahogany dressing table features in Shashi Deshpande’s account. Pics Couresy/Om Books; (right) Dad’s easy chair. Shinie Antony’s account reminisces about this piece of furniture with fondness

mid-day: How did the idea for ExObjects emerge? Was there a trigger, or were such thoughts stewing for a while?

AT Boyle: THE trigger was the deaths of my parents during COVID-19. The aim of exObjects (Om Books) is not to produce factual accounts or diary writing or grief memoirs. Instead, its motivation is to look hard, imaginatively and with the hope of finding peace through new understanding. I believe that it’s only by not swerving away, keeping a focused gaze, spending time, over time considering difficult emotions that things that lie under the surface, some that perhaps were not said at the time, are able to show themselves and be perceived in a more holistic sense, from a distance.

ADVERTISEMENT

The rose gold watch features in one of AT Boyle’s accounts; (right) Ramona Sen’s heartfelt account involves her father’s favourite blue Santa tie

The rose gold watch features in one of AT Boyle’s accounts; (right) Ramona Sen’s heartfelt account involves her father’s favourite blue Santa tie

MD: What is the most challenging part of processing grief, especially when it comes to objects like those in the book?

Shinie Antony: In grief there is no template, no manual, no deadline. One copes on the spot, making up coping mechanisms as one goes along. In life no one prepares us for anything, least of all for sudden loss of a person. There is a huge hole in our life, and we try to go on, knowing that is the norm, the done thing. It takes a while, but the flamboyance of grief does pixelate gradually into a dull background noise. We slowly become aware of the things left behind. What to do with the clothes, the medicines, the glasses, and the watch? Weeding out, going through everything, however brisk and smart we try to be is a journey of its own. That’s when we decide what to keep. Maybe a brooch or a book. What reminds us of them the most? What contains within it a joke, an argument or eccentricity?

AB: The word ‘processing’ is pivotal here. Process requires a structure of sorts; the structure we all need in times of loss, a time when much of what we know and what we expected to happen becomes suddenly fragmented. The shock of hearing about my mum’s death through a phone call from a nurse at the hospital was pummelling. And I found solace in the beginning to tap out on my keyboard the swell of emotions as they arrived in my emotion-fuddled brain. This was followed by an experience common to many: the sorting out of possessions in a now-empty home. It was during this sorting out process that I received many new surprises — objects that I was seeing for the first time like the tiny icing sugar dove made by a baker in Preston, Lancashire, for their wedding cake. I write out this discovery in the exObject called Peace in the book.

When I broadened out the healing power of writing in this form to others, I found a different kind of satisfaction, joy and understanding in supporting other writers on their individual journeys through loss. Their objects of focus were not necessarily the death of someone close, but included climate and heritage. This part of the process enabled me in a way to stand outside my own grief.

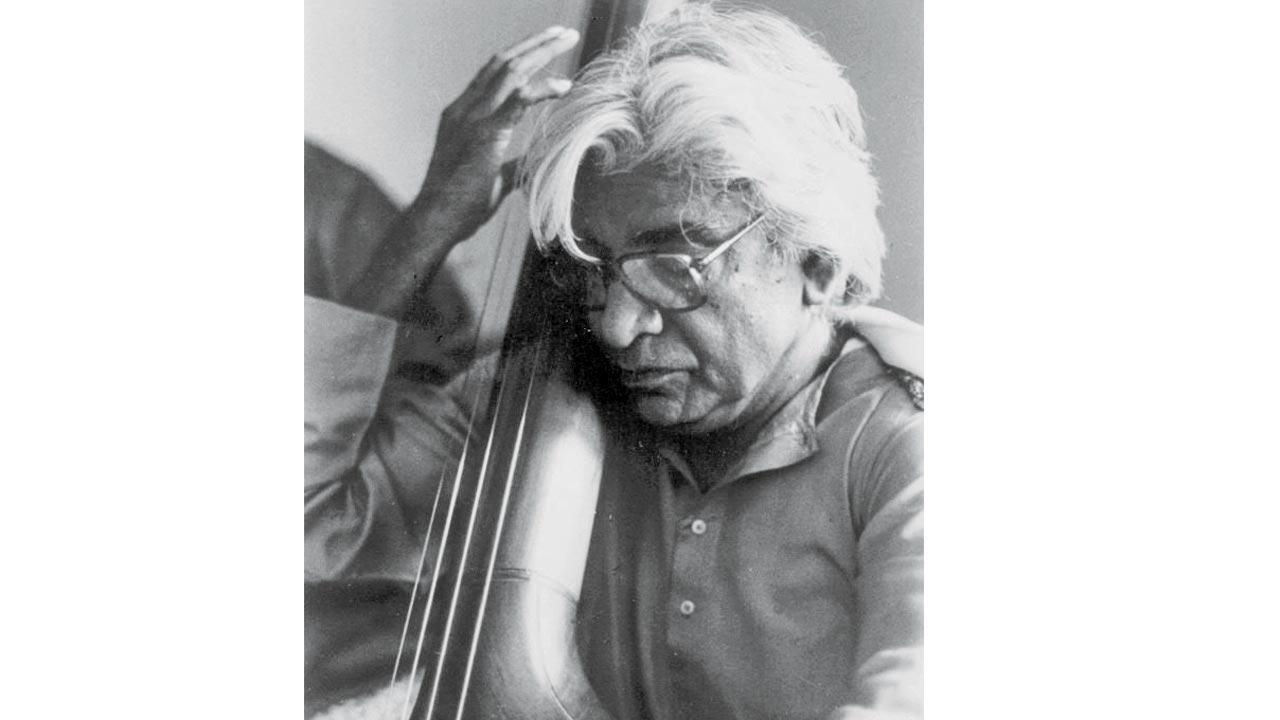

A father lost in music. Gajra Kottary recalls her father’s musical moments in her piece

A father lost in music. Gajra Kottary recalls her father’s musical moments in her piece

MD: Editing sensitive content would have required extreme care. Tell us about the process.

SA: The writers were coming in with sensitive memories. Shashi Deshpande with a dressing table mirror given by her grandfather, Jerry Pinto with a lost soft toy, Jaishree Misra with the love letters her late parents wrote to each other. Vikram Sampath, remembering his mother; with Gajra Kottary and Ramona Sen, their fathers; childhood memories of fireflies and keys to a house that no longer exists. They had the difficult job of articulating their loss. As editors we came in very lightly.

SA: All of the writers’ chosen objects serve as a nexus of the emotional interactions that bind us to people and place. Running through the collection of stories is compassion — compassion for oneself in tackling the challenge of grieving, but importantly also in seeking to find universal truths from individual experiences. There is a comfort in feeling connected, in resonating with other people’s narratives. We all begin with a sense of finality, but through objects we can arrive at the sense of a new beginning.

Shinie Antony

Shinie Antony

MD: How challenging was it to write your own pieces?

SA: Losing my dad is still a puzzle to me. I can understand death only in the context of others. The fact that I won’t be able to talk to my father or have his passionate support for anything hare-brained I come up with is baffling. I don’t have the right words to console myself. It doesn’t make sense that anyone so central to your life can drop out just like that. Bringing him back as he used to be, as he was, at first felt exhibitionistic: here he is, as I remember him, in bits and pieces, buffering. Agonising over which anecdote defines him best. But then he took over. They always do.

AB: Once I had circumscribed what, or rather whom, the focus of my pieces would be, it was less of a challenge than sitting in the miasma of grief that had until that point been unarticulated.

My dad, the entertainer and ‘out-there’ parent was the obvious subject for my own scrutiny. But I often find it best to test a concept by starting at the toughest end. So, dad was consigned to the back-stage while I turned wholeheartedly to understanding more of who my mum was. I wanted to understand her as a girl, a young woman and a younger mother rather than focusing solely on the more recent old-age. The writer’s challenge is to recognise our strong emotions but not be overwhelmed by them, perhaps as you would for self-survival, through instinct, step back from a giant wave encroaching on the beach where you stand. That is not to say that we completely swerve from addressing the challenges inherent in addressing something so raw. A neat question to pose can be: What is the risk of not addressing our emotions?

When we observe something of importance from a distance, we may discover greater clarity for ourselves. If we can journey from the personal to the universal, we have a greater chance for our story to resonate with someone who does not know us, whose life experiences are very different from our own.

AT Boyle

AT Boyle

MD: Despite its core focus, a positive, bright vibe flows throughout the book. How was this possible?

SA: Yes, that is something we instinctively agreed on. This is not so much about the pain as it is about the sheer joy the objects they left behind symbolise. We are all sentimental about those we love, but to be portraying them as they were requires reportage. A gathering of facts about them, coming up with a half-smile or individualistic trait — It is lovely to pull them out of the photograph albums in our minds into our midst, into the present.

AB: Most people’s lives are tragic-comic. We experience high points and low points. The highs would not be so worthy of celebration if each day was run at a happy fever pitch, every moment a heightened emotion. The important element that I hope comes through is the ‘bright vibe’ you describe: my wonderful mum, in spite of old age and extremely difficult circumstances caused by an international pandemic and caring for my dad with now two forms of dementia, was guiding me still. She was conveying through soundless gestures, through a thick window that all was not lost. And so, all was not lost then. And it is not lost now.

MD: Grief is deeply personal, and cannot be quantified. What can readers take away from this special curation?

SA: Grief is unavoidable, even inevitable, and it is not possible to have a strategy for this. But at some point we realise loss is universal, and that a kind of hand-holding is possible. That as long as we remember there is a strange hum in the air, like they are back. As the memory of a silly fight, favourite food, a movie they disliked... We trace them back to their laugh.

AB: The key to these accounts is the object itself, which can be intangible (such as an as yet unrealised dream) or a tangible object (such as the unique chocolate, pecan and walnut cake my mum would make in her Lancashire kitchen). Importantly, the high-quality photos of some of the objects referenced in our stories work with the text to elicit the multiple aspects of an important relationship with someone or something lost.

Through the invitation to connect with the personal stories in this book, readers can fill in some of the gaps they perceive in their lives. Here lies the possibility of framing a more hopeful reality and moving out the hole of a seemingly unremitting loss.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!