India’s foreign film Oscar entry sets us thinking about single-screen cinemas of our childhood

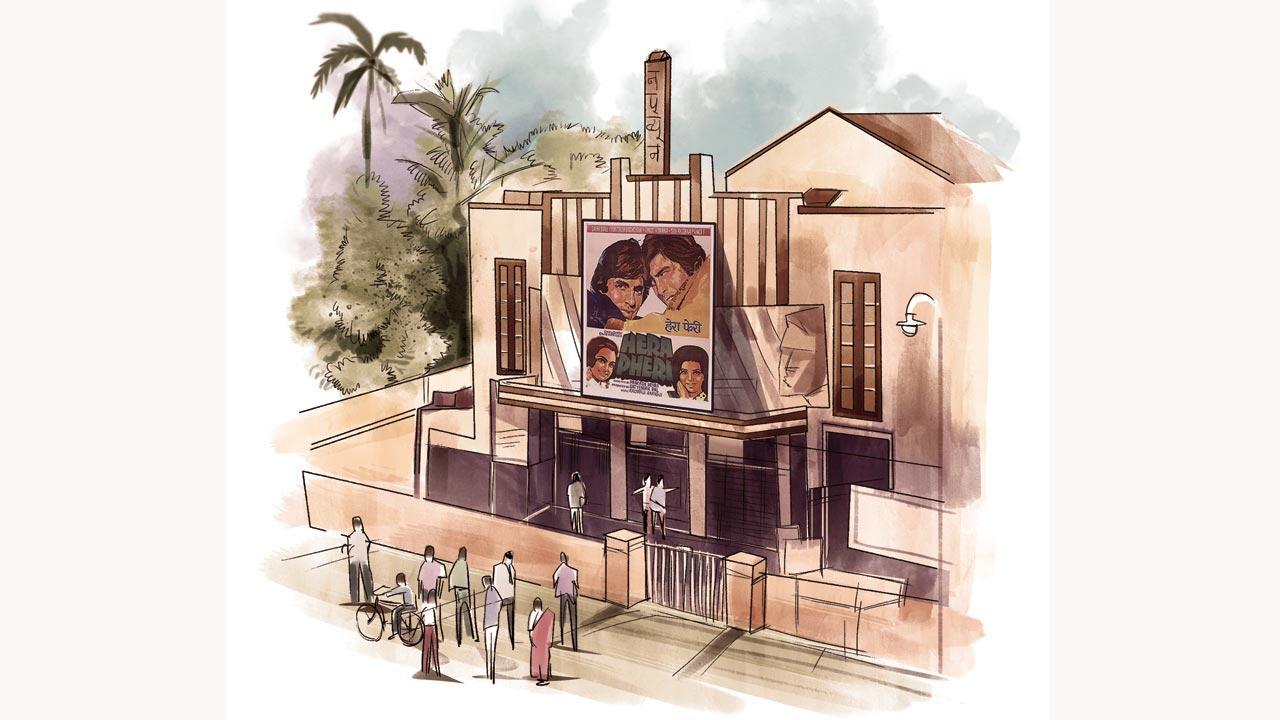

Illustrations/Uday Mohite

All the way back from viewing Chhello Show, Pan Nalin’s exquisite paean to single-screen theatres, I was flooded with thoughts. Of the weekly pleasures afforded by at least half a dozen standalone movie halls. Nicely within walking distance of my Hill Road home in Bandra.

All the way back from viewing Chhello Show, Pan Nalin’s exquisite paean to single-screen theatres, I was flooded with thoughts. Of the weekly pleasures afforded by at least half a dozen standalone movie halls. Nicely within walking distance of my Hill Road home in Bandra.

New Talkies was most regularly frequented, not simply for being the closest, but because it fed a steady diet of both Hindi and English films. Western films were what we otherwise mainly headed southside for, thrilling to The Sound of Music, My Fair Lady, the original Doctor Dolittle and Fantasia, the visionary Disney animated classical music anthology.

ADVERTISEMENT

Those rates proved pricier than New Talkies’ Rs 3.30 Balcony and Rs 2.20 Stalls seats. Earlier generations enjoyed—for 1 princely rupee—a 75 paise ticket, 10 paise cycle parking charge, 10 paise interval batata vada and 5 paise Panama cigarette puffs.

My first film ever was One Hundred and One Dalmatians there. That 1960s Cruella de Vil scared considerably less than Glenn Close’s manic role reprisal in the version my kids devoured 30-odd years later. On its heels came Born Free, with Elsa loping towards the camera in her leonine splendour. The effect felt unnervingly close to our seats. I clutched my mum’s arm murmuring, as if to reassure her, “Shush, she can’t come out of the screen.”

Laurel and Hardy reels, Knock on Wood with Danny Kaye’s ventriloquist doll, spaghetti westerns my elder brother begged for, we saw them all thanks to the Sunday Picture Society the parents signed us up for.

Soon we booked our own seats. When ticket queues once wound past the cinema corner on to Waterfield Road, my brother left his place in the long line (trusting the boy behind to hold it), sprinting to our home mere minutes away. He pulled me out, wanting to share his discovery: A sturdy baobab (gorakh chinch), facing the post office-Bhabha Hospital pavement. Recognising the rare, sparse-leafed African tree from a book we adored—The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupery—we blinked with delight at our introduction to the Fat Lady of Bandra, as this local landmark is dubbed till today.

Occasional mess-ups, with the spool not reaching the projection room punctually, seldom resulted in disappointment. Cinema is cinema, the management decided. Instead of the expected Roald Dahl adventure one Sunday morning, I saw Zehreela Insaan, New Talkies’ fresh Friday release.

That glitch resulted in lifelong fandom of the sprightly Neetu Singh-Rishi Kapoor jodi. With best friend Nimmi, I saw every single film they paired for. Even our convent assembly hall inexplicably screened them, including Rafoo Chakkar, where frames of Rishi and Paintal in drag understandably distressed the nuns. St Stanislaus, brother’s alma mater across the street, rented soberer fare like Guddi and Koshish, Gulzar’s career-defining, nuanced portrayal on disability and acceptance.

Going to New Talkies meant patronising Blue Circle beside. From craving the shop’s crisp butter wafers, we graduated to kababs at Casbah, the beer bar opposite. Just logical, big bro’s pals assured, having snuck me with their underage selves into the auditorium for a “Strictly for Adults” film, The Italian Job.

Among serious Hindi cinema offered by our beloved talkies were Kora Kagaz and Khushboo. As Nim and I emerged from an evening show of the latter, based on Sarat Chandra Chatterjee’s novel, Panditmashai, we realised Gulzar and Hema Malini were walking out with us. Sans intrusive flashbulb-popping paparazzi or muscled security, the dignified director and leading lady awaited their cars. Passers-by heard strains of RD Burman’s score for Khushboo from the theatre steps. Not the epauletted live band of premieres—glittering affairs in the 1970s—striking up tunes outside foyers, this understated quartet played “Bechara dil kya kare”.

The bolder Burman music attracting us to repeat tickets for the same film was that of Hare Rama Hare Krishna. At Bandra Talkies on Linking Road. ‘Phoolon ka taro ka’ and ‘Dum maro dum’ gained cult status as India’s rakhi and hippie anthems. That ‘Dum maro dum’, a sparkling cultural touchstone of cinema history, barely missed inclusion, seems unthinkable. Another story, that.

Alarmed at the preferred beat at home sliding from edifying ‘Diya jalao’ to brazen ‘Dum maro dum’, our starchy aunt, Dhunmai, protested. Summoning us to her bedside table, dad’s oldest sister blasted forth a cassette cascade of Saigal and Sanyal songs with hopes of reform. “These children went to Bandra Talkies again. Junglee jehva motta thasey, they’ll grow wild,” she warned the parents. “Especially your girl. Will go off with some filmwala before you know it!”

Bandra Talkies was touted arch-rival to New Talkies. We hotly disagreed. The Linking Road theatre was no match for our favourite. But, smitten bad by Shashi Kapoor, we braved queues snaking from an Advance Booking window (textbooks tucked underarm to avoid faltering school grades) in the Bandra Talkies compound—for good tickets to his Salim-Javed scripted blockbusters such as Deewaar, Trishul, Immaan Dharam and Shaan, lest House Full boards loomed. Years later, on my confessing this at an interview for The Illustrated Weekly, Gentleman Kapoor, as the press anointed him, gave that charming crooked-toothed grin.

Malls replaced halls. While New Talkies sprouted Globus and Marks & Spencer, Bandra Talkies became Shoppers Stop. Bus conductors still refer to this halt as “Bandra Talkies” though. Also hurtled from cinema to commerce was Neptune, down Guru Nanak Road from the railway station, transforming to Veena Beena Shopping Centre. A memorably mature watch, packing in a double treat of the young Kapoors and their Uncle Shashi, was the sensitive Doosra Aadmi.

What got us giggling inside Neptune amid crazy rain that compelled school to declare a holiday? That we waded through swirling waters for the Bachchan-Vinod Khanna entertainer Hera Pheri in a building named for the Roman sea god. Bachchan buffs enveloped us. We dug Khanna’s deep chin cleft.

Least patronised was neglected Nandi Talkies near Bandra talao. If cheap pricing was a given, so were constantly conking air conditioners and rat clans nibbling samosa crumbs. The shrieks of horrified ladies front-rowed from us drowned squeaks of the vermin foraging around their feet. All this in the exaggeratedly dramatic climax of Subhash Ghai’s Kalicharan, with gravity-defying Shotgun Sinha slicing the air to clobber villains, with Kalyanji Anandji’s deafening theme chorus roar, “Kaaleecharan-Kaaleecharan-Kaaleecharan-Kaaleecharan.” Four times in case we couldn’t figure out the extent of his flying prowess.

When Yash Chopra’s Kabhi Kabhie totted a successful second run here following its gala multi-theatre release, the basti ke tapori refrained from advertising it with their customary shouts of “Chalo aao, seeti bajaao” at the Nandi entrance.

Scoping films was evident from ticket lines. The game of fortune was sharpest observed at hugely popular “Gaytee-Gayleksee”, as black marketeer lads skulking in the lane referred to Gaeity-Galaxy-Gemini. Opening with Ramesh Sippy’s Seeta Aur Geeta, the astral-named troika was an unerring hit ya flop barometer.

Superstars often frequented them, vainly attempting incognito appearances, slipping in unshaved or sporting thick sunglasses. They prayed the impassioned public responses would be confined to whistling, clapping, dancing in the aisles, rather than ribald hooting and primal ripping of rexine upholstery. Practical minded, the management hired a resident darzi to quickly restitch damaged seams. In an age far from absurd “crore club” number crunching, insecure stars supposedly bought seats to beef up box-office optics.

It was in Gemini, the smallest, that we felt raw excitement appreciating one of our first “new wave” films after Shyam Benegal’s Ankur. His path-breaker Manthan, the 1977 National Award winner peaked incredible collective pride in audiences with its very title sequence announcing: “500,000 farmers of Gujarat present…” Financed by each farmer of the Gujarat Co-operative Milk Federation contributing Rs 2 to the 10 lakh-budget, Manthan is possibly the first feature film created without a production house. Vanraj Bhatia’s haunting “Mero gaam katha parey” rings in the head nearly half a century on.

Four screen siblings added to the triplets of SV Road in the 1990s—Glamour, Gem, Gossip, Grace—converted the complex to G7, scheduling Hollywood movies as well.

The mid-1970s’ Drive-In Theatre was an experiment we rushed to be part of. At a spot on eight hectares of east Bandra-Dharavi, we sang along with shimmy-shaking Rishi Kapoor in Nasir Hussain’s Hum Kisise Kum Nahin. Mahim marsh mosquitoes biting us sore, we readily forgave its ABBA-copied melodies than the fact that he chose a film which should have had twinkle-toed Neetu with him, not debuting Kaajal Kiran.

Its initial novelty notwithstanding, reels reportedly stolen by drunks and carloads of customers cribbing about snipped endings caused the Drive In’s

inevitable closure.

PS: Rest in peace, dear Dhunmai. Your niece didn’t exactly “go off with some filmwala”. She only married into a family of proprietors of some Grant Road cinemas.

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at [email protected]/www.meher marfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!