And you played tough, giving back as good as you got

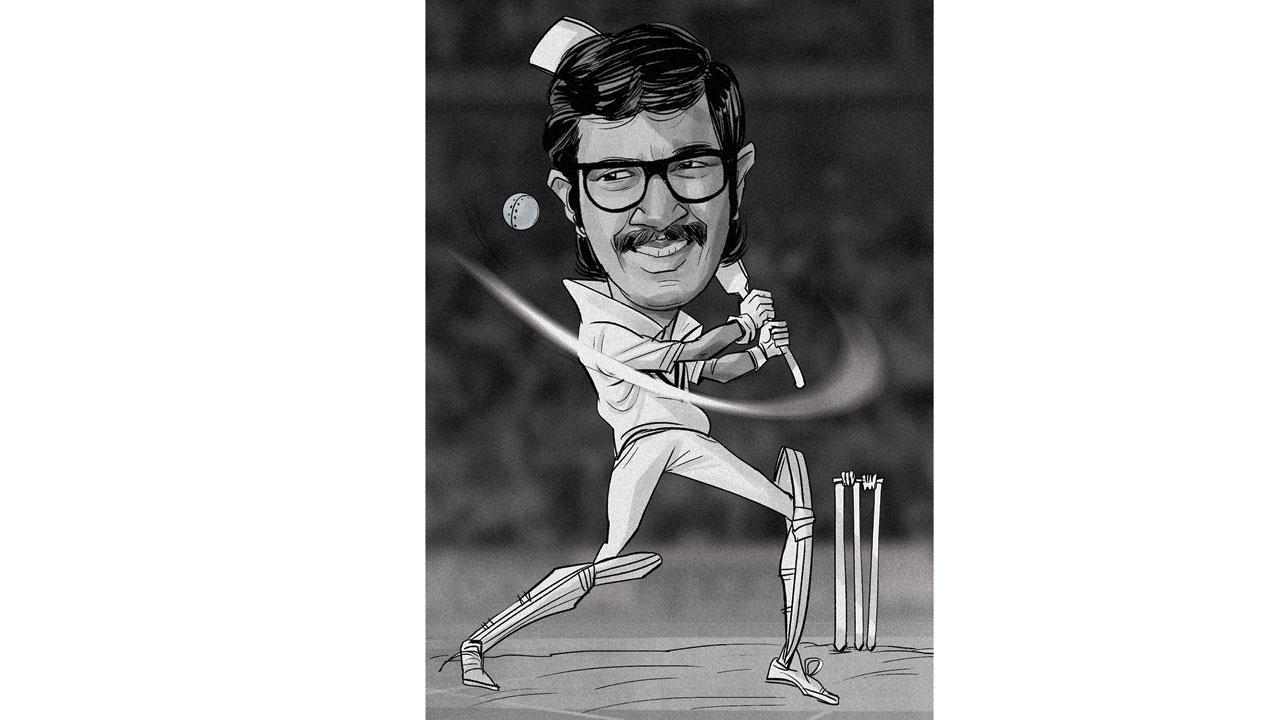

Illustration/Uday Mohite

Dear Anshu-maan (that’s what the West Indians called you). I first saw you bat when I was twelve. It was 1974, the West Indies were here, Clive Lloyds men, for a five Test match series—we were down two nil, and in the third Test at Eden Gardens, Kolkata you came to bat, you were all of 22, on your debut, you had a total non-sportsman-like build—lanky, bespectacled, opening the batting, helmetless against the speed of Andy Roberts, and the guile of Lance Gibbs. I remember thinking, oh boy, this dude seems more like a nerd than a cricketer—you had your collar up, and you had a walk, a particular walk, I‘ll never forget, because I tried to imitate it—it wasn’t an Imran Khan swagger, it was a side to side motion, vulnerable but vital—and you could bat, bowlers couldn’t get you out, you kind of hung in there, leaving the ball alone with a kind of lazy elegance with all the time in the world.

Dear Anshu-maan (that’s what the West Indians called you). I first saw you bat when I was twelve. It was 1974, the West Indies were here, Clive Lloyds men, for a five Test match series—we were down two nil, and in the third Test at Eden Gardens, Kolkata you came to bat, you were all of 22, on your debut, you had a total non-sportsman-like build—lanky, bespectacled, opening the batting, helmetless against the speed of Andy Roberts, and the guile of Lance Gibbs. I remember thinking, oh boy, this dude seems more like a nerd than a cricketer—you had your collar up, and you had a walk, a particular walk, I‘ll never forget, because I tried to imitate it—it wasn’t an Imran Khan swagger, it was a side to side motion, vulnerable but vital—and you could bat, bowlers couldn’t get you out, you kind of hung in there, leaving the ball alone with a kind of lazy elegance with all the time in the world.

ADVERTISEMENT

Suddenly, the country was rooting for you—there is no doubt in my mind, that the greatest batsmen are those who play their best against the best bowling attacks of that era and the West Indians far and away were the finest bowlers of the 70s/80s. And you played tough, giving back as good as you got.

I remember this day distinctly, the Windies and India were tied two matches each, you were only two Tests old, but you had become a household name—I went to a Protestant school, and we had a Reverend Sundaram, who would take us through a morning prayer once a week—on this particular Friday, India were battling to save the Mumbai match, at the Wankhede—the Reverend finished the Lord’s Prayer, and then added, “I’d like us to say a special prayer for Anshuman Gaekwad, that he may help us save the follow on this morning, come on young man you can do it.”

And then came that infamous Sabina Park Test match in 1975, you and Sunny Gavaskar went out to bat, you could the sense the “baying for blood” from the Windies, they were incensed at us having pulled off the biggest heist in cricket having scored 406 to win in the previous match, and they went for you in particular, a young Michael Holding and a beast of a guy called Wayne Daniel, body blow after body blow, they aimed for your head, they hit you on the ear, blood ran from it, they’d got their bloodbath—but you batted a whole day, 81 runs in 450 minutes—eventually you had to retire, they had injured your ear drum, and your hearing was affected since, inspite of three operations.

I gotta say, maan, because of you I nearly failed all my exams—I’d sit for hours in front of a black and white ECTV, concentrating on your strokeplay instead of Chemistry and Mathematics. Many year later, I met you at Baroda airport, and as we waited for our baggage to come off the conveyor belt, I introduced myself and spoke to you of my great admiration for your grit and guts, especially against the West Indian quicks, first Andy Roberts and later Michael Holding and Bernard Julien and Vanburn Holder.

You smiled and said, that if you stood upto the West Indians, both the players and the crowd, they developed great respect for you…” Gavaskar, Amarnath and I were … “Sunny Maan, Jimmy Maan and Gaekwad Maan, they can play, maan” I’m truly sorry that you’ve left us, Anshu Bhai, you were really one of life’s good guys, a phenomenal batsman, a no-nonsense coach, in an age of sixes and instant T20 cricket, and flamboyance and five minutes of fame, you came from a bygone era.

You dug in, you gritted it out, you wore down the bowlers, you never gave away your wicket, it’s a pity you only had 40 Test matches to show for your gifts, but you shaped a part of my black and white childhood, rest well sir, rest well, as you take guard, up in the heavens.

Rahul daCunha is an adman, theatre director/playwright, photographer and traveller. Reach him at [email protected]

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!