Six persons per square metre is the norm. Mumbai’s locals carry 16 at rush hour. I learnt what this means when I boarded the Virar Fast

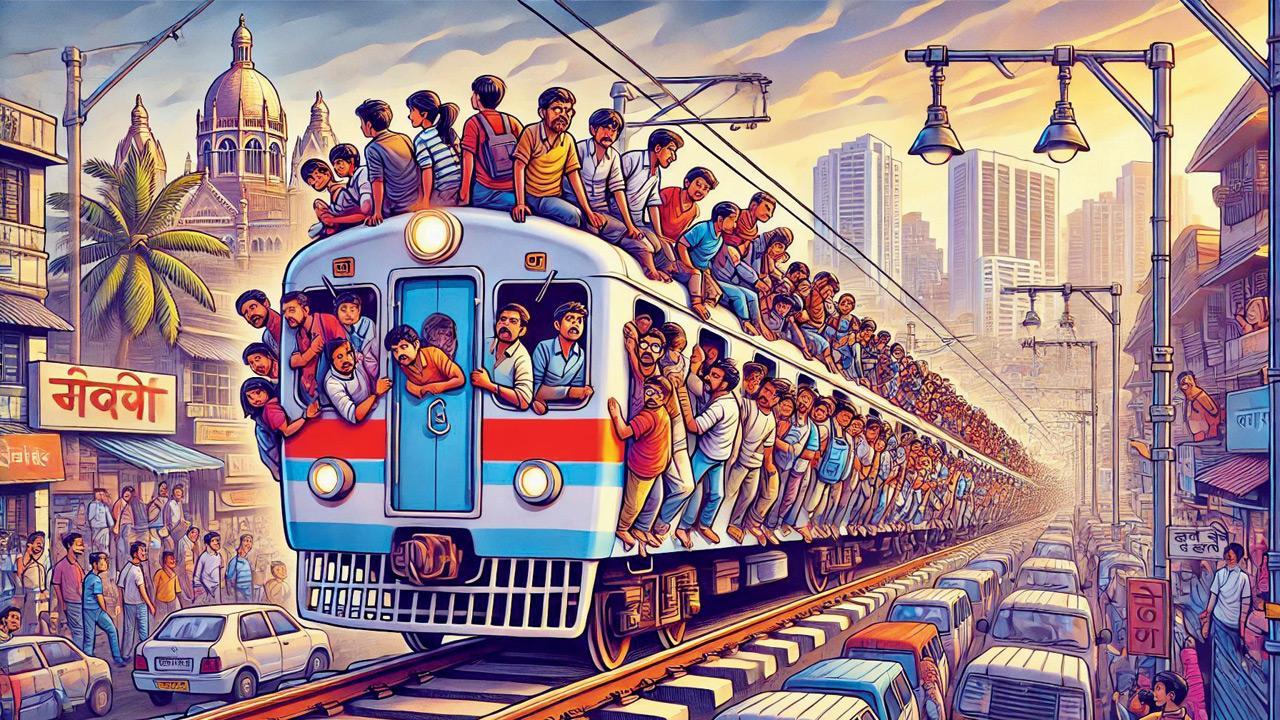

Mumbai’s suburban trains squeeze 14 to 16 commuters per square metre at peak hour, a number so wild that they had to coin a special term for it: Super Dense Crush Load. Illustration by C Y Gopinath using AI

To be fair, I was warned.

To be fair, I was warned.

ADVERTISEMENT

A fellow at the station had said, “Better not take the Virar Fast.” But he mumbled it, like a mild afterthought, so I took it as a suggestion rather than a dire warning.

It was evening rush hour at Churchgate station, a key terminus on the world’s most daunting suburban train network, carrying the equivalent of Switzerland’s population daily. I was trying to decide the best train to get to Andheri, but the three-language announcements were turned to gibberish by the rally-level reverb added to them. No one was listening anyway; they were focused on the baffling code on each platform’s LED signage.

The bright white sign above my head read —BO06:47S03

The first one or two characters (someone kind explained) represented the destination, in this case BO for Borivli. The next four characters, all numeric, showed the scheduled arrival time. The next character, always F or S, signified a Fast or Slow train. The last two positions, also numeric, told you the minutes left for the train’s arrival.

Should I board a slow train and endure a 45-minute ride to Andheri or get there in 25 minutes on the next fast train? While I pondered this, the Borivli Slow filled up and left. The platform sign changed to VR06:53F01. My eyes fastened only on the letter F.

Here it was, my Fast train home. But as it pulled in, the station turned into a war zone.

At its worst moments, Churchgate is like a landmine: harmless until it explodes. Everything looks deceptively mundane, but everyone is a coiled spring, taut and alert. They know that any moment, without warning, a cataclysm will shatter the peace when the next train enters. Their lives will depend on moving like lightning and with the brutal force of a sledgehammer.

The sound starts even before the train stops, the thundering hooves of hordes of humans barrelling into the train, like panicked wildebeests crossing the Mara River while crocodiles try to eat them. They hurtle into compartments like missiles, looking left and right with wild eyes for empty seats.

I got swept in on this tsunami of bodies, a piece of Western Railway flotsam. There was no question of finding a seat; everything had been taken in the first five seconds flat. I stood wedged at the back of the coach between eight human beings of varying sizes, weights and aromatics.

I wish someone had told me this was the Virar Fast. And that I was about to meet the Super Dense Crush Load.

A crush is the result of a vehicle carrying more commuters than it was designed for, forcing commuters to stand too close to—or “crushed” against—each other. In transport economics, a crush load describes how many commuters can stand in a square metre without undue discomfort.

On a sliding scale of comfort, a crush load of 5 is considered optimal, with enough standing room and personal space for commuters. At a crush load of 7-8, commuters would still be able to play video games on their smartphones but at 11, they’d have to hold the device above head level. At crush load 12, all notion of personal space disappears; it becomes bodies without borders.

Mumbai’s suburban trains squeeze 14 to 16 commuters per square metre at peak hour, a number so wild that they had to coin a special term for it: Super Dense Crush Load. At this level, the crowd begins to display fluid characteristics, moving like a single viscous body of flesh. As far as entering and exiting the train goes, it’s each one for themselves.

The train stopped at Mumbai Central, Dadar and Bandra and it dawned on me that no one was getting off. Everyone on this train was going to Virar.

Andheri was up next and I could see no way of reaching the exit. I began tapping shoulders to ask if anyone could somehow, against all odds, let me past. More shoulders were tapped as the word went around the coach; everyone looked kind but helpless. We were all frozen in rictus.

Then someone remarked, “Senior citizen! Getting off at Andheri!”

That went viral. Some began to say, “Make way for Senior Citizen!” Some craned their necks to see Senior Citizen.

Senior Citizen, meanwhile, stood where he had been compressed, packed and cling-wrapped, devoid of ambition, initiative and hope, completely resigned to being disengorged at Virar.

Then something entirely unexpected began. Biologists call it peristalsis, referring to the rhythmic cycles by which intestines squeeze out their contents each morning.

A large fleshy man somehow slid past me, pushing me into the space he had occupied. Another human mass slipped behind me, thrusting me a tad closer to the exit. Senior Citizen stayed limp and unresisting, squeezed forward thus like toothpaste from a tube, till somehow, amazingly, he found himself at the exit, night air blowing at his face.

The train reached Andheri. The coach cheered. Everyone exhorted Senior Citizen to be without fear and jump.

While I weighed the pros and cons, someone gave me one last push and, exactly like yesterday’s breakfast, I was deposited on the platform, hot and steaming.

But alive.

You can reach C Y Gopinath at [email protected]

Send your feedback to [email protected]

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!