By embracing spontaneity as part of my creative process, I found out that I relish my writing most when it is truly metabolic, emerging from a place of having internalised lived experience

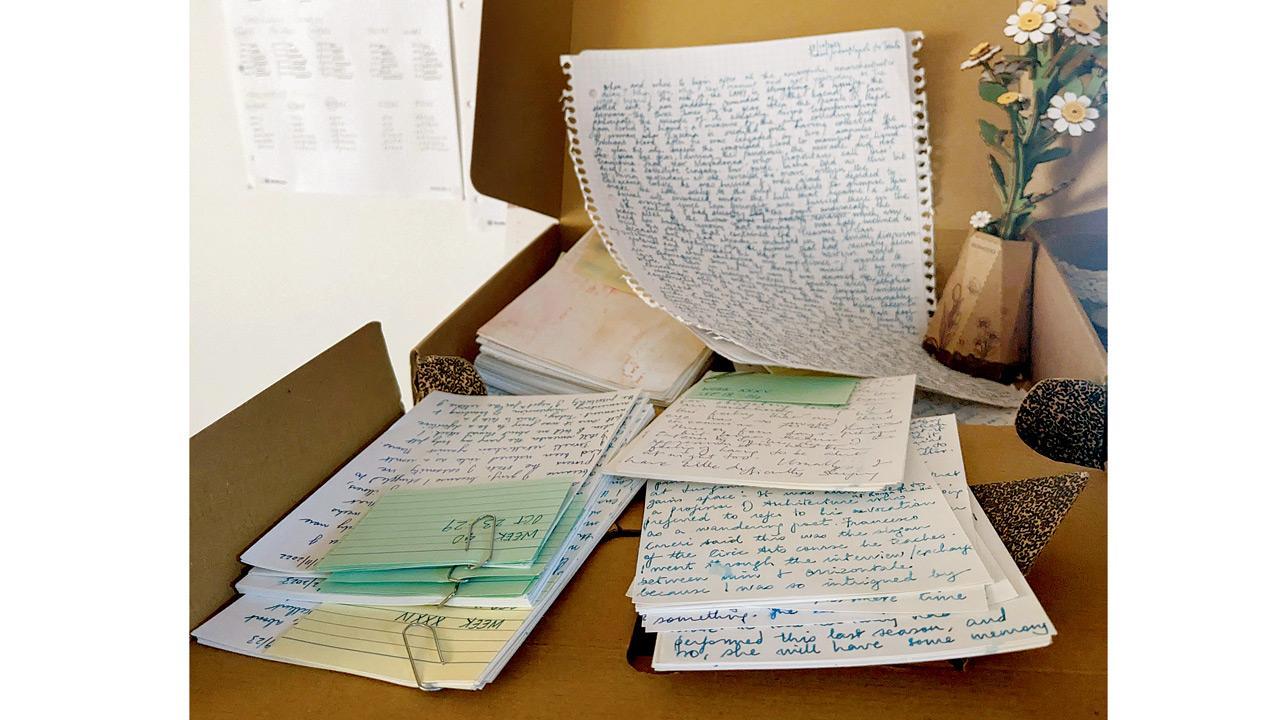

The handwritten manuscript of my next book, Milking Time, in a cardboard box. I couldn’t believe that all these notes I had been making on what look like scraps of paper amounted cumulatively to at least 60,000 words. Pic/Rosalyn D’Mello

Last week I transcribed the last piece of handwritten text that was intended as the conclusion to my next book, Milking Time. It was strange to suddenly encounter my shoebox project as something digitised, converted from a Word document to a PDF file, easily accessible to anyone who might want to read it. I couldn’t believe that all these notes I had been making on what look like scraps of paper amounted cumulatively to at least 60,000 words. The eeriest feeling, however, was how impressed I felt by my own style. Most of the book had been written through 2023, and for the longest time, I was afraid of transcribing it because I couldn’t guarantee I would like what I had composed. As long as the notes were tucked away in the brown cardboard box, they were something I could feel proud of. But confronting them and transcribing each word meant that I had to contend with their worth. Could they be interesting to anyone other than me, was the biggest question on my mind.

Last week I transcribed the last piece of handwritten text that was intended as the conclusion to my next book, Milking Time. It was strange to suddenly encounter my shoebox project as something digitised, converted from a Word document to a PDF file, easily accessible to anyone who might want to read it. I couldn’t believe that all these notes I had been making on what look like scraps of paper amounted cumulatively to at least 60,000 words. The eeriest feeling, however, was how impressed I felt by my own style. Most of the book had been written through 2023, and for the longest time, I was afraid of transcribing it because I couldn’t guarantee I would like what I had composed. As long as the notes were tucked away in the brown cardboard box, they were something I could feel proud of. But confronting them and transcribing each word meant that I had to contend with their worth. Could they be interesting to anyone other than me, was the biggest question on my mind.

ADVERTISEMENT

At some point, however, it ceased to matter. External validation felt counterproductive and even redundant. What was important was that I sent the book out into the world and launch its trajectory. I never really had control over the book in any case, considering I had chosen to basically write it using the timespan of weekly instalments. Each week, from mid-January 2023, I would imprint my thoughts on borrowed office stationery using my ink pen. At some point I had the idea to do this over the course of 39 weeks, to mimic the period of time our firstborn was inside my womb, since it was a book about maternal subjectivity. I only wrote when I was able to find snatches of time in between the haze of early motherhood, which meant I rarely planned or plotted my thoughts. I allowed for a total free flow. I embodied that Clarice Lispector dictum: ‘I let myself happen’ on the page.

Writing is an act of surrender, like prayer. You may have certain inherent intentions, intonations and inflections, and while there are writers out there who are so in control of their craft, they know exactly how to mould the words in order to produce an effect; writers who think of sentences as raw material that can be re-shaped and re-fitted to produce or enhance a literary effect, I found out, by embracing spontaneity as part of my process, that I enjoy being a writer who is not over-invested in effect. I enjoy my writing most when it is truly metabolic, when it comes from a place of having internalised lived experience. In that sense, I no longer use writing to process my emotions. Rather, writing is what I do after the act of having processed feelings and sensations. Where before writing felt therapeutic, now it feels joyous, because it is not intended to be a rant or a coping mechanism against anxiety or a way of rationalising an emotion. It is a space of wandering, a site where my thoughts can walk or hop or sit still or hike. It has become a thing in and of itself, something I do that is both within my control and outside of it.

My whole life I felt convinced that one did things in order to master them, and not being good at something meant it was better to not do it and instead spend time with an activity or a hobby that one had innate skill or talent for. The other day, I went through my pile of cotton tote bags. Being in the art world, one tends to quickly accrue a collection. I pulled out one blank bag and decided to jump into the embroidery project I had been planning in my head. It was too late to print out the image I had of the two-tailed mermaid, and too late to find carbon paper to transfer the image, so I found myself drawing it instead on the corner of one side of the bag. I had recently purchased some embroidery threads. I chose a rust red one for the tail and googled a good outline stitch and every other evening, when I find myself with time and energy, I continue with the work.

I can see my failings quite clearly, especially when I compare my work to my mother’s. But it doesn’t seem to matter, or the fact that I am such a newbie to this ancient art form doesn’t deter me or throw me off. Because I am no longer operating from a site of insecurity, from the wound that seeks to be healed by being validated by others. I am working from the more joyous realm of curiosity and an eagerness and willingness to learn. Not to seek praise but as an act of praise itself. I am allowing the playfulness of a hobbyist to seep into my writerly vocation. It’s a total twist in the paradigm, a complete shift in how I was taught to approach craft and art.

Deliberating on the life and times of every woman, Rosalyn D’Mello is a reputable art critic and the author of A Handbook For My Lover. She tweets @RosaParx

Send your feedback to [email protected]

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!