Harappans were very different from the Vedic people—they were urban, preferred trading and had no armies, while the Vedic people were pastoral, preferred raiding and war

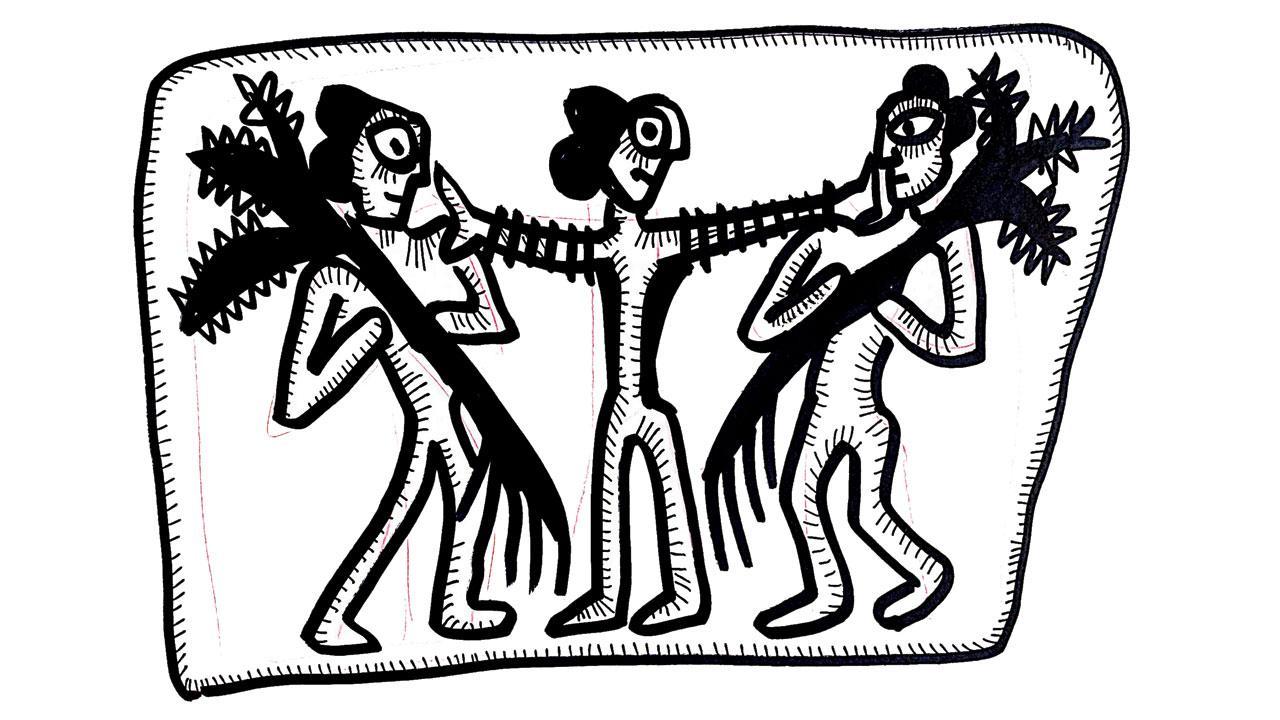

Illustration/Devdutt Pattanaik

We often trace the origin of Hinduism to Rig Veda, dated to 1,500 BCE. But the Rig Veda contains ideas that we can trace to Harappan civilisation. For example, Rig Veda mantra 8.47.17 refers to a measurement system based on increase by a factor of two (1, 2, 4, 8,16) also found in Harappa. How is that possible? Harappan cities ceased to exist five centuries before the Aryans arrived. Also, Harappans were very different from the Vedic people—they were urban, preferred trading and had no armies, while the Vedic people were pastoral, preferred raiding and war.

We often trace the origin of Hinduism to Rig Veda, dated to 1,500 BCE. But the Rig Veda contains ideas that we can trace to Harappan civilisation. For example, Rig Veda mantra 8.47.17 refers to a measurement system based on increase by a factor of two (1, 2, 4, 8,16) also found in Harappa. How is that possible? Harappan cities ceased to exist five centuries before the Aryans arrived. Also, Harappans were very different from the Vedic people—they were urban, preferred trading and had no armies, while the Vedic people were pastoral, preferred raiding and war.

ADVERTISEMENT

It is possible this happened because Aryans who immigrated were mostly men and so, probably married women from post-Harappan cultures with memories of Harappan ideas. As Hinduism emerged in later times, we find it full of ideas that are only partly traceable to Vedic ideas. In Harappan seals we find ideas that are still valued today by Hindus and Indians in general.

Harappan seals represent tree worship, animal worship, the importance of the number seven, and a yogi. This has been recorded before. Horns hold a special place. Many tribal communities still use giant horns as part of ritual to show power. Curiously, after Persian art came to India about 500 years ago, the horn came to represent demons, something that was never done before.

What often goes unnoticed is that the seals refer to wild and domestic animals. Are these indicators of different Harappan cities that clearly collaborated with each other? Despite vast distances between cities, they follow the same measurements, modular thinking and standardisation and there is little evidence of war or standing armies. Wild animals include tiger, deer, crocodile, bison and rhino. Domestic animals are the humped bull, the goat, the buffalo. Collaboration is shown by making wild and domestic animals circle a yogi-like figure, or my merging animals to create composite beasts. Composite beasts are sacred in Hindu myths, but monsters in Greek myths.

One repeated motif is of a tiger turning back to see a man on a tree, reminding us of the tension between nature and culture. This divide is crucial to Vedic literature where Sama Veda divides melodies into songs of the forest and songs of the settlement.

Harappan seals speak of tiger-goddesses, or sphinx, who are still part of Pahari miniature paintings. Seals show us women stopping men from fighting with spears in one seal and trees in another. We find no image valourising war but several seals opposed to violence between humans. Animals are shown fighting: bulls attacking each other. While humans hunt bulls, humans are discouraged from fighting. One bird-faced woman stops tigers from fighting indicating an aversion for territorial behaviour.

Can we say that the doctrine of ahimsa originated in Harappa? Harappans were traders and traders hate war and violence as it disrupts markets. Also, many of the animals seen on Harappan seals such as bull, elephant, and rhino became icons of the Jain Trithankaras, who promoted non-violence, and are still venerated by trading communities. Of course, the Harappans were not vegetarians - they ate all kinds of meat, including cattle. We still use vessels they invented—handi, thali, lota, circular with rimmed edges. And we are still insular like them, in love with walled communities, gates and courtyards. We love, even worship, water like them. But we still don’t respect sanitation as they did.

Devdutt Pattanaik writes and lectures on the relevance of mythology in modern times. Reach him at [email protected]

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!