The 1980s and ’90s signalled effective public service advertising nationwide, with Alyque Padamsee instituting the SOMAC (Social Marketing and Communications) unit within Lintas

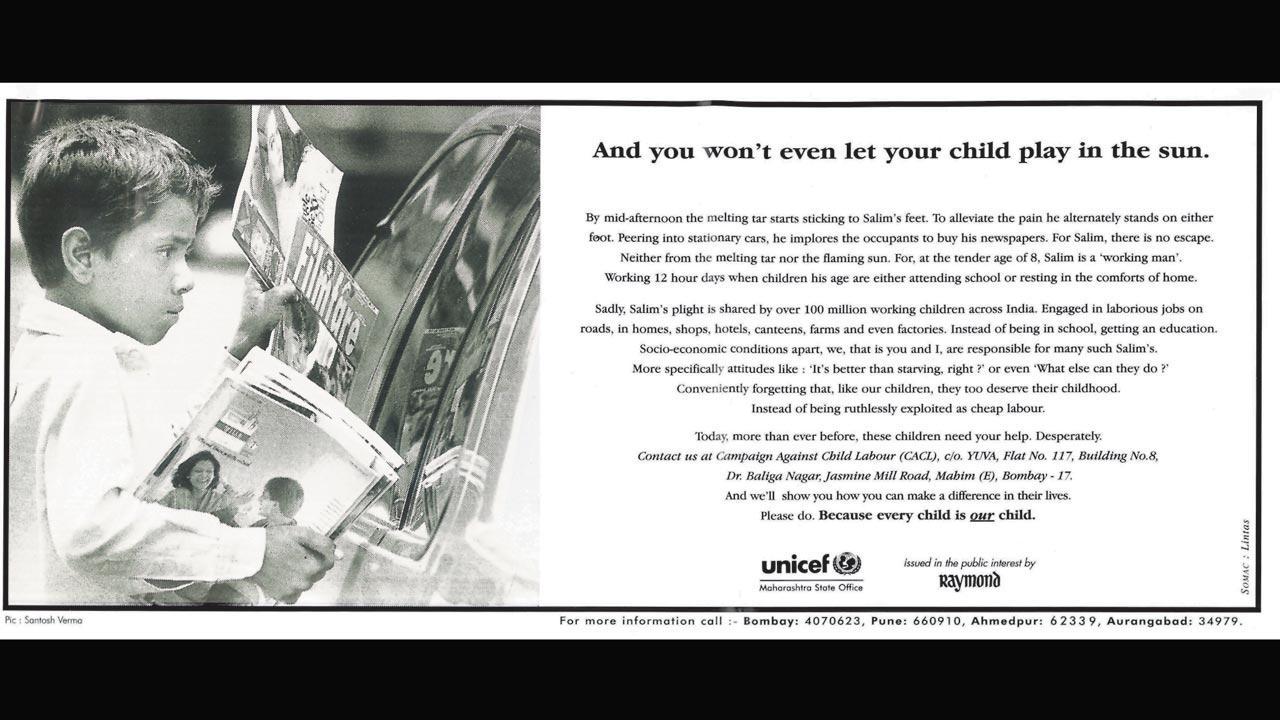

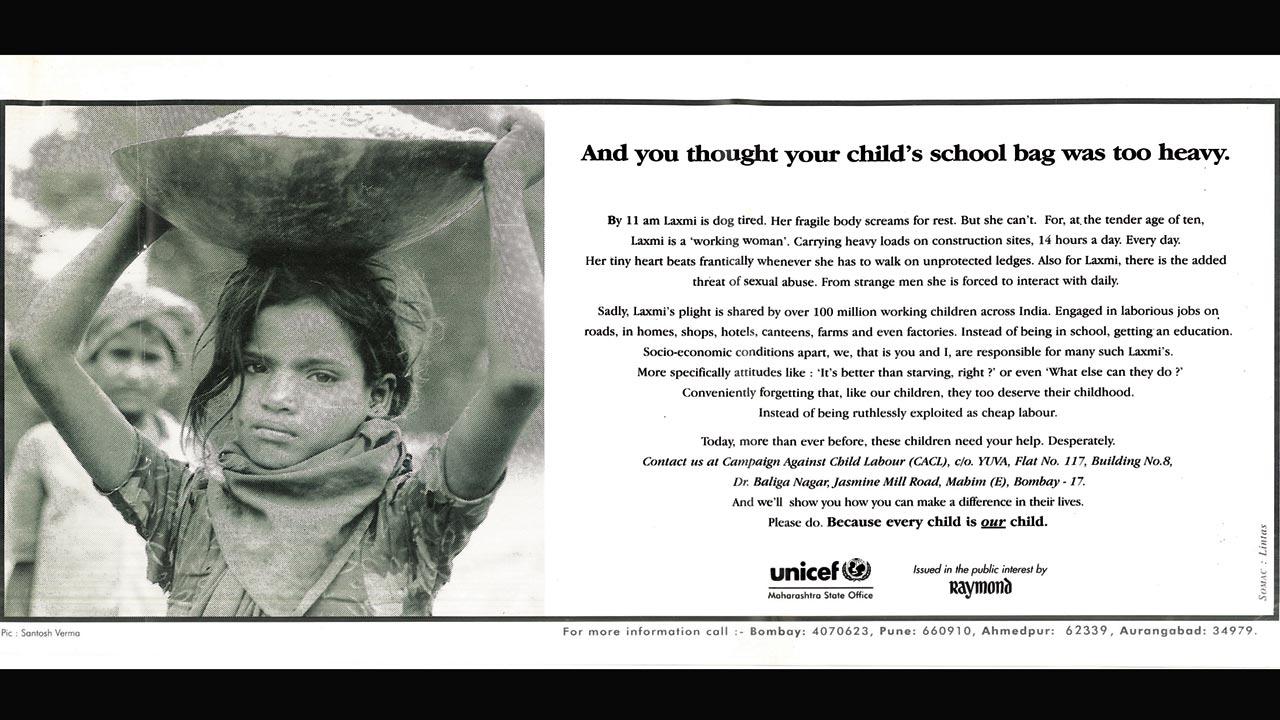

Examples of SOMAC advertising in partnership with Campaign Against Child Labour and UNICEF

The genesis of SOMAC resulted in unprecedented and far-reaching support to concerns countrywide. Vitally harnessing and extending the power of communications to public service advertising, its long-running campaigns, pitched pan-India, changed thousands of lives.

ADVERTISEMENT

The NGO and donor community saw value in knowledgeable professionals finding impactful solutions to social causes. Though never the motivation, SOMAC won the Global Award at the New York Festivals Advertising Awards and First Prize from the Association of Business Communicators of India.

Former collaborators recreate the lessons learnt from that memorable early era of public service communication, from the 13th-floor Express Towers office at Nariman Point where it all began.

Why was SOMAC unique and how did you get involved with it?

GK: Before SOMAC became a special department within Lintas, Alyque Padamsee created several public service ads (PSAs). Tara Sabavala worked with him on an HIV and AIDS programme for the Government of Maharashtra. SOMAC was a natural progression, exclusively handling communication for the development sector—becoming a full-fledged division offering professional communication strategy and media planning for national and international NGOs, and community-based groups wanting to make a difference. Tara left to head Concern India. After I joined, SOMAC was “official”.

TS: I was part of Lintas Public Service work from 1989 to 1992, before SOMAC was an independent unit. Alyque was already creating 30-second films available gratis for TV channels and cinemas, on subjects from dowry to the dangers of tobacco. Lintas personnel on creative and client service teams had the opportunity to volunteer pro bono for NGOs coming to us for communication material. Alyque demonstrated you can serve the nation right from where you are, with the same skill set you’d use for advancing in your place of work.

NO: I’d worked with an HIV prevention programme in 1990 focusing on Kamathipura sex workers. We designed the SOMAC campaign with the government, providing and broadcasting accurate information on a mass scale.

VC: When I joined SOMAC in 1994, what stuck out was that an ad agency invested in a dedicated team creating social issues communication, something no other agency had done.

Gulan Kripalani, Radical Transformational Leadership practitioner-coach; Tara Sabavala, social development professional; Varsha Chawda, behaviour change communication & brand planning strategist; CY Gopinath, author, filmmaker, cook, nomad; Nandini Oomman, global health specialist & founder-CEO, The Women’s Storytelling Salon and Pervin Varma, development sector consultant

Gulan Kripalani, Radical Transformational Leadership practitioner-coach; Tara Sabavala, social development professional; Varsha Chawda, behaviour change communication & brand planning strategist; CY Gopinath, author, filmmaker, cook, nomad; Nandini Oomman, global health specialist & founder-CEO, The Women’s Storytelling Salon and Pervin Varma, development sector consultant

How was this PSA responded to then?

TS: Often the involvement needed persuasion. I recall meetings with the Indian Express editor, to run the Causes and Concerns series—well-researched articles on education and population. There was no budget. We produced campaigns if the media did so free of cost.

GK: We were a great asset to fledgling initiatives trying to be visible, simply unable to afford paying agencies. Most NGOs hardly had money to spend on communication of any kind.

NO: AIDS wasn’t recognised as a public health problem in India till the late ’80s. The biggest challenge was a campaign communicating everyone’s risk of contracting HIV. We had to destigmatise this. Initially, many acted as if this was a foreign problem or thought gay men, sex workers and drug users alone were at risk. We created a campaign which didn’t scare but raised awareness of HIV transmission.

CYG: PSA advertising was internally funded a lot. We worked on shoestring budgets, exhilarated to come up with brilliant ideas not costing a bomb. There wasn’t systematic assessment or a push to measurable, monitor-able action. When work was collaborative with NGOs, the metrics of response and impact were usually built into the project. A single Lintas/SOMAC intervention might be part of a larger plan.

PV: Exposure to PSA left an indelible mark, profoundly influencing career and life choices like mine. Lintas birthed social communications as a discipline in India. The first batch of Sumit Roy’s trainees, we expected to hear Alyque’s success stories—the legendary Lalitaji and Liril campaigns. Unpredictable as ever, he shared public service films Lintas had produced, hardworking pieces of communication changing hearts and minds.

What were SOMAC’s outstanding campaigns?

TS: Our campaign against amniocentesis for sex determination was instrumental in the state banning this practice. We also ran a question-answer column with Indira Jaising and Lawyers Collective, inviting questions from women and provided guidance on using the law to access their rights. Though it was in English, we were flooded with mails from across the country in every conceivable language. Our HIV campaign for the Maharashtra government addressed misinformation and stigma. This was before SOMAC formed as an entity.

GK: The largest was for DFID (Department for International Development) in collaboration with NACO (National Aids Control Organisation). The “Healthy Highways” campaign we designed and produced aimed to prevent AIDS among truck drivers and sex workers. It covered every state, with over 40 NGOs in constant touch with truckers crisscrossing highways.

Nationwide, outreach workers communicated with drivers at dhaba rest stops and sex workers in brothels. Multilingual materials—mobile photo exhibitions (a SOMAC invention telling stories with blown-up photos, real locations, actors, dialogue in word bubbles), films, flip charts, booklets, audio tapes, condom boxes, bumper stickers, posters, fliers—reached transport company managers, STD doctors on highways, truckers’ wives, dhaba and bar owners. We trained workers on best using the little time they had with the drivers to stress the importance of protection.

What we did with PSI (Population Services International) was unconventional and innovative. Visiting brothels, we talked to sex workers about condoms, did loads of infotainment programmes including popular dances on specially made stages in Kamathipura. John Matthew Matthan’s film for us, Bodyguard, was a huge hit. We gave free passes to sex workers, their customers and pimps.

Another influential collaboration was with Campaign Against Child Labour (CACL) and UNICEF. A corporate partner paid for media releases. Hundreds of directly affected labourers were taken off streets and put into schools.

CYG: I was involved in a movie-hall intervention where sex workers were given tickets for favourite clients. The film paused before a song or dance and a theatre skit would be performed on HIV survival skills. We scripted a dynamic sex worker character, Champadevi, who became their mascot.

NO: The AIDS campaign was my first encounter with the public sector in a project productively maximising private-public partnership. SOMAC couldn’t have implemented state-wide public health communication without the DHS (Directorate of Health Services), Maharashtra, and the DHS couldn’t have designed the mass media campaign without SOMAC content and copy.

VC: “Balbir Pasha Ko AIDS Hoga Kya?” is one of Lintas’ most impactful pan-Indian campaigns. That experience fed into our ethos of communication based on real consumer insights. Balbir Pasha became a catchphrase and Harvard Business School case study brand builders refer to even today.

“Help a Child Reach 5”, winning a Cannes gold and Effies award, campaigned across India, Indonesia and Kenya. It supported Lifebuoy’s mission to change children’s handwashing behaviour, preventing under-5 diarrhoeal deaths. Our 4-year leprosy campaign for the Ministry of Health helped eradicate the disease.

Which other aspects of this journey have been gratifying?

NO: This was an exciting time in India because different organisations worked on HIV prevention as the public health issue became visible. Each played a role in the response to HIV in Bombay—raising awareness, advocating for rights, delivering actual programmes to communities served. No single entity can tackle public health, partnerships between different bodies are crucial.

VC: I split my 25 years at SOMAC/Lintas into pre and post Balbir Pasha eras. Funny how your recommendations are valued once you have one such campaign under your belt. Sarkari babus notorious for boring communication were willing to step out of their safe zones. I don’t distinguish between brand and cause advertising. SOMAC used brand advertising tools in social campaigns with effectiveness.

PV: Many of us switched from the corporate to social sector because Gerson da Cunha and Alyque took Lintas to mean so much more than an advertising company. I worked for relief in the riots, bomb blasts and AGNI. The mission brought people together to celebrate their differences rather than be torn apart by them. How we currently miss such vision and leadership in endeavours.

CYG: As far as I can tell, public service advertising now covers more topics, from COVID safety and climate change to being woke, racism, white supremacy, the importance of hugging and disease prevention.

GK: We spent time understanding issues, listening to people affected, attempting holistic communication, nurturing an enabling environment for change to happen. Monthly themed messages on our Babulnath hoarding carried a contact number for people to connect with a relevant NGO, volunteer for it.

Following 1993’s terrible violence, we worked with NGOs, CBOs, educational institutions, the Sheriff’s office… on “Hands of Harmony”, stretching from Colaba to Mulund. Citizens too frightened to leave home for weeks became the human chain. That event visibly helped start some healing.

TS: Alyque instilled in us a certain rigour not restricted to media campaigns. After the Babri Masjid demolition, we organised a public meeting to diffuse hate and fear. Alyque showed by example how to “do”, not stand silent observer of what needs changing.

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at [email protected]/www.meher marfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!