Amazed how little India’s GenZ and late millennials appreciate significance of what happened this week, 30 years ago!

The economic reforms of 1991 when Dr Singh was the finance minister and Rao the PM ushered in a New India for its middle and upper classes

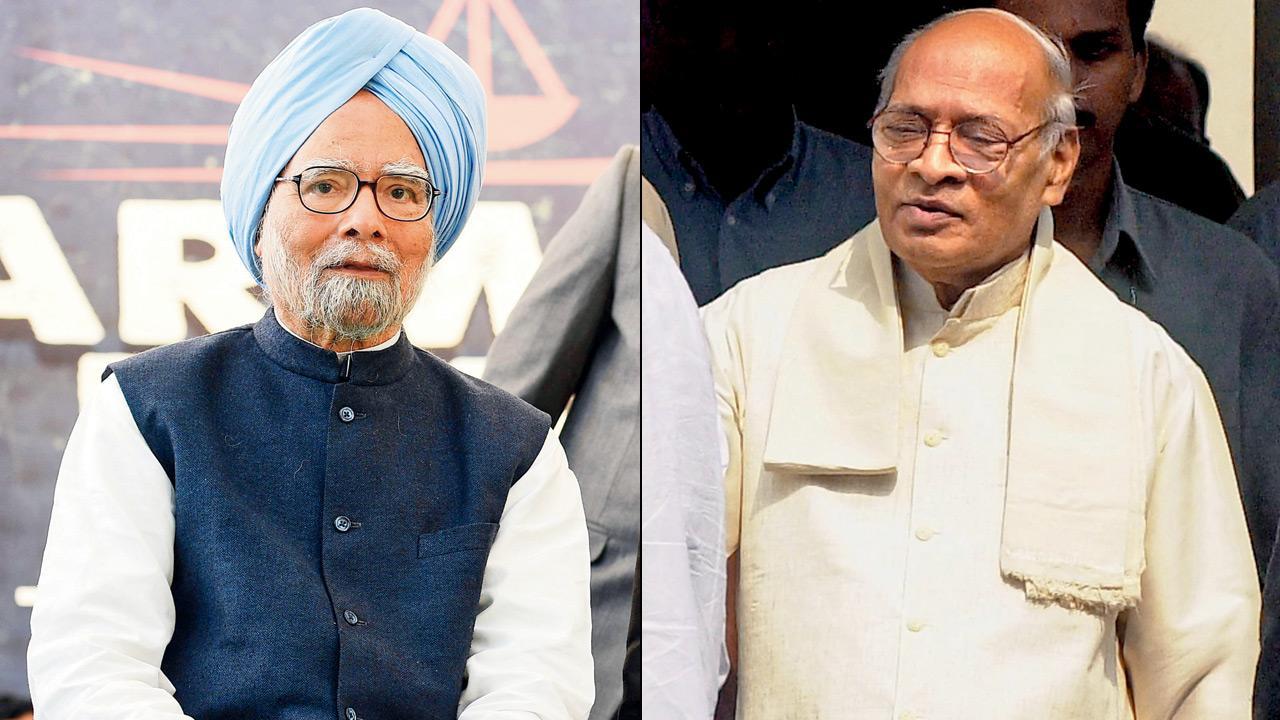

Of his two terms as India’s Prime Minister (2004-14), Dr Manmohan Singh famously suggested, history will judge him better. What about his most historic moment itself—as finance minister, delivering the landmark budget speech on July 23, 1991, that singularly altered the course of India’s economy, with Victor Hugo’s line, “No power on earth can stop an idea whose time has come… Let the whole world hear it, loud and clear. India is now wide awake!”

ADVERTISEMENT

Meaning, awake to do business—allowing foreign investments, companies, products; dismantling import restrictions, lowering tariffs. Getting rid of several paranoid lists, licences, permits and quotas that were based on India’s fear of both big business, and competing with the First World. Therefore it actively believed in state-run businesses, and closing off the economy altogether!

Economic reforms, put in place within weeks, ushered in a New India, for its middle and upper classes anyway. It’s debatable how much of the credit must be split between Dr Singh, and his (then) Prime Minister PV Narasimha Rao, a protectionist, who as chief minister of Andhra Pradesh in the early ’70s declared, “We will not tolerate a capitalist—even if he is a Dalit!”

Rao, retired from politics, became India’s unlikely PM in 1991; post the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi, during the election campaign that brought his Congress party to power. Gandhi, in comparison, was a liberaliser. In 1985, he had lifted restrictions on Indian companies to import equipment for plant expansions.

Companies could buy what they liked abroad—so long as they paid for it through loans taken and settled abroad too. Now returns on such investments usually take long. But these loans were short-term.

Which means these companies regularly dipped into India’s foreign exchange reserves to pay back said loans. This is cited as one among many reasons for a balance of payments crisis that stared at Rao, when he took over as PM, with India left with just enough forex reserves to last for three weeks!

Soon as he entered office, Rao was handed a document prepared by the previous (Chandra Shekhar) government, explaining how deep in shit the Indian economy was, and the reforms essential at that moment for a bailout. Conditions the IMF would also set for the same. So you could argue, Rao only did what any PM would’ve.

He also decided on a complete non-politician to take over as India’s finance minister, which shows the strength of his intent. He had two choices before him: Dr Singh; and IG Patel, director of London School of Economics. Patel declined.

According to historian Vinay Sitapati’s brilliant Rao biography, Half Lion, one of the early reforms/suggestions that Dr Singh drafted for the PM, had left the boss unimpressed. Rao was looking for radical measures—what was the point of having Dr Singh on board otherwise?

One could suggest Rao also used Dr Singh as human shield, in case things didn’t pan out well. The gentle sardar was made the face of reforms. His head could easily roll likewise, since Rao was surrounded by socialists in party and parliament.

For instance on July 1, 1991, the Indian rupee was devalued by 9 per cent at one go. On July 3, the government had decided to drop the rupee value by a further 11 per cent! Which is when Rao developed cold feet, gauging political response to the first move.

He wanted to stall the second. His top crew made excuses, such as being unable to reach the RBI governor’s landline phone (or some such), and smartly/slyly went ahead! Currency devaluation chiefly relates to enabling exporters compete better in international markets. Such is how India’s economic history was being rewritten.

What does this mean to you, if you were either born after 1991, or thereabouts? My spot surveys suggest: Nothing. If you’re much older, and from the urban middle/upper-class, you’ll have striking personal memories. Whether it’s the mile-long lines outside KFC at New Friends’ Colony—first foreign fast-food chain in India—and reports of swadeshi nuts attacking such outlets. Or that ad of Remo Fernandes announcing the entry of ‘Leher’ Pepsi—we could actually drink cola the rest of the world did!

To give perspective to GenZ, on how 1991 is the year that separates urban India’s landscape from a period film—you only saw Ambassador, Premier Padminis and few Marutis on streets before. Banked with SBI, Bank of Baroda etc (ICICI, HDFC came up in ’94). Phones were government owned. Of course there was only Doordarshan on TV. Technically satellite broadcasters—Zee started in ‘91—were neither legal nor illegal, until 1995. The liberal government chose to look away.

Not saying everything about reforms were good—that it transformed India’s health and education (should have), or had a dramatic impact on employment (it’s been negligible to negative).

Here’s the thing though. There’s only one thing of striking significance in 1991, as India’s economic turn, which I came across online recently. That Metallica’s self-titled album, Pearl Jam’s Ten, G N’ R’s Use Your Illusion I & II, Nirvana’s Never Mind, Red Hot Chilli Peppers’ Blood Sugar Sex Magik, and Soundgarden’s Badmotorfinger came out 44 days of each other! And Indians could shortly buy them at the same time as their place of origin.

Mayank Shekhar attempts to make sense of mass culture. He tweets @mayankw14

Send your feedback to [email protected]

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!