In his riveting autobiography (pray, why wasn’t he a writer), late Fali S Nariman relives an arduous three-week trek from Rangoon to Delhi via Imphal where his family landed as refugees after Japan overran Burma during WWII

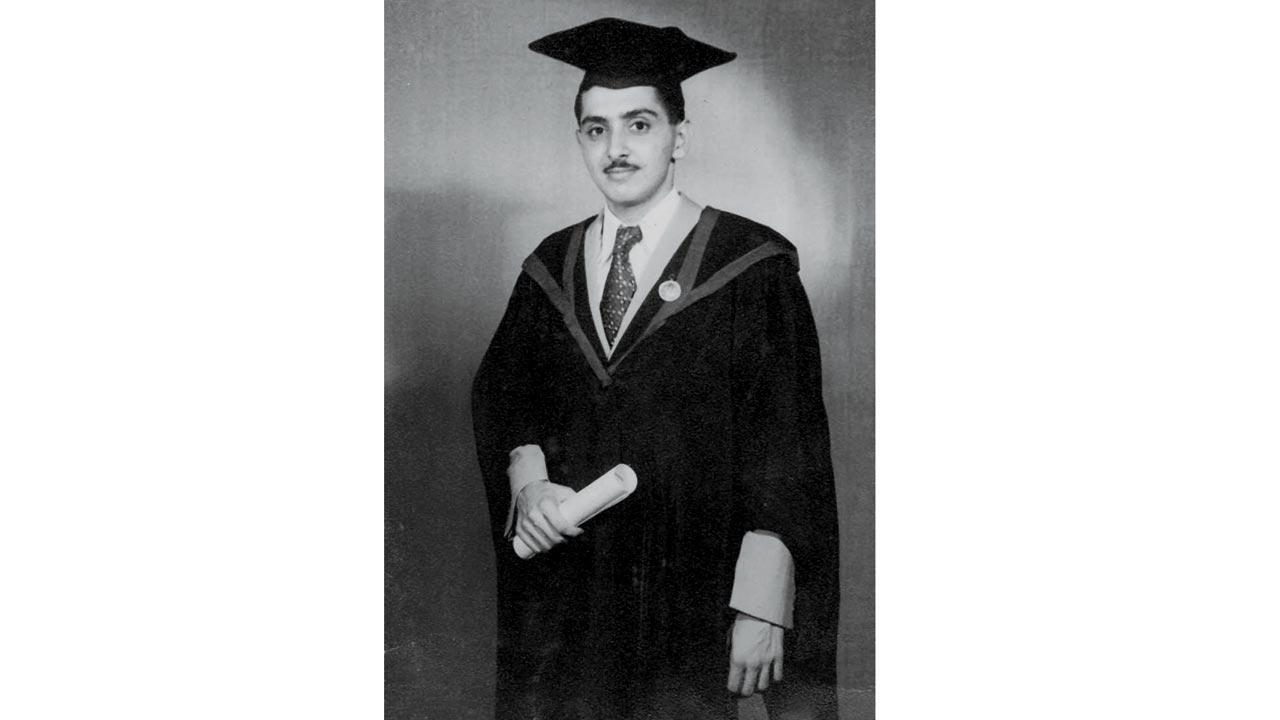

Fali Nariman with his Bachelor of Law degree. Pics Courtesy/Hay House India

I grew up in Rangoon (then capital of Burma) in the 1930s under the loving care of my parents (I was their only child). Spoilt? I am afraid so; I was always ‘Baba’ to my parents. We lived in a rented doubled-storied bungalow (Kennedy House) near the Royal Lakes. I can truthfully describe my childhood as ‘a cloudlessly happy one’. The clouds gathered, but only later when I was 12 years old in December 1941, when the Japanese bombed Rangoon and then invaded and quickly conquered Burma. When I was five, I was thrilled to take part in a children’s programme broadcast over All Burma Radio—it was not a speech or a poem, but a catchy tune called Rendezvous. I did not sing or play it—I whistled it. I believe it was a hit, but I have had no requests since then to whistle catchy tunes! Another early recollection is when I was six years old in standard I of a coeducational school. The principal (an imperious lady, Miss Hardy) announced one morning at assembly that King George V had died. She then added that she had been instructed to declare a holiday, at which there was loud cheering. Miss Hardy promptly revoked the declaration of a holiday, as a result of which the school was fined a substantial sum by the director of education! And we all whispered under our breath: ‘Serves her right’. After a year, I moved on to a regular boy’s school (The Diocesan Boys School) where the principal, LS Boot, was much less impetuous. Progressing from one class to another, a good student but of average ability, I reached standard VII where my class teacher was WW Rollins. And what an excellent teacher he was—his lectures in geography, illustrated with maps prepared by him, have left an indelible impression on me.

ADVERTISEMENT

Nothing very eventful disturbed the even tenor of our lives in Rangoon–until Japan declared war on the Allied Powers after bombing Pearl Harbour on 7 December 1941. Within a week, the city was targeted by air attacks. We witnessed intense and incessant bombing, and spent more time in our makeshift air-raid shelter in the garden of our home than in our bungalow. Soon we moved north to Mandalay for what we thought would be a brief sojourn. This was on the advice of the then governor of Burma, Colonel Sir Reginald Hugh Dorman-Smith, who confidently told my father at one of his war council meetings: ‘Don’t worry Sam, we will get rid of the Japanese in a month or two.’ My father was taken in by this assurance—how could the chairman of the War Council of Burma be wrong? But he was wrong—hopelessly wrong. Contrary to Dorman-Smith’s expectations, the invasion by the Japanese Army was so swift and fierce that for us the road back to Burma’s capital city was cut off.

Young Nariman (middle) with his parents Sam and Banoo Nariman, in the most modern car of the times (1932)

Young Nariman (middle) with his parents Sam and Banoo Nariman, in the most modern car of the times (1932)

We were then forced to embark on a long overland journey to India with what little we had carried to Mandalay: it included several boxes of office records (life policies and general insurance policies); the head office in Bombay greatly appreciated my father’s thoughtfulness in saving these important documents. The overland journey to India lasted 21 anxious and eventful (but for me, also memorable) days, through forests by bullock-cart (which took about seven days), along the Upper Chindwin.

River by country-boat (for the next seven days), and then (for a week more) up and down steep mountainous terrain on foot and by doolies till we reached the Indo-Burma border—all this without any travel agent’s guidance or even a tour map to help us along the way! But not without excitement. When we were on the mountainous terrain we were providentially saved from being trampled to death by an elephant. The Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation owned about 400 trained elephants who were used at Rangoon for removing logs of wood from forests in Lower Burma. These pachyderms were brought up north on account of the war, and were made to carry into British India the baggage of the corporation’s senior staff (only the baggage of the sahibs). Our luggage was carried by Manipuri porters whom we picked up at the starting pointing of our trip. These porters were extremely scared of elephants. They would insist on waiting for a full hour after each cavalcade had passed. On one such occasion, after an entire group of 19 elephants had passed us, we resumed our journey on foot (and doolies).

Fifteen minutes later, when we were on a straight narrow path with a deep ravine on one side and a steep hill on the other, we saw a lonely elephant trundling down without his mahout. The nimble-footed porters left our luggage on the narrow path and clambered up the trees on the hillside. But we had to stick as close as we could to the side opposite the ravine with my parents saying their prayers. They feared it was the end. Just then, the leader of the troupe (a young Englishman), who had trained the elephants, came back looking for the missing one. When the beast was just 30 yards from us, ambling down to where we were (and would have certainly trampled us), this good man seeing the plight we were in shouted in Burmese, ‘Shamba! Shamba, pyam ba, pyam ba’ [‘Elephant! Elephant, go back, go back’]. Apparently, something clicked in the recesses of the small brain of the trained elephant. He obeyed his master’s call and turned around as he was commanded. We then implored the porters to pick up our baggage lying strewn on the narrow path, and quickly rushed-on. A few days later, the same young Englishman met us at a refugee camp in Imphal and told us that he had great difficulty in reining in the animal which had gone berserk.

In the trek out of Burma, apart from biscuits and sweets which my mother had thoughtfully stocked up for the journey, there was not much to be consumed by way of food. In early February 1942, we arrived at a refugee camp in Imphal where we ate our first hot meal after a three-week trek. It was here that we were given the sad news of Rangoon having fallen into the hands of the Japanese Army. There was no going back now. We took the train from Dimapur to Calcutta (now Kolkata), and from there another train to Delhi (happily it is still Delhi), where we stayed for a while with my father’s old friend, Dady Cooper, and his wife, Rutty, who very kindly gave us shelter in their spacious bungalow at Barakhamba Road.

Our arrival in New Delhi marked the first turning point in my life— landing as a refugee from Burma, uprooted from hearth and home.

Excerpted with permission from Fali Nariman: Before Memory Fades; Hay House India

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!