Third-culture kid Kritika Arya—who has lived and grown up across India, the UAE and UK—explores questions of identity and belonging in this excerpt from her book of illustrated autobiographical essays

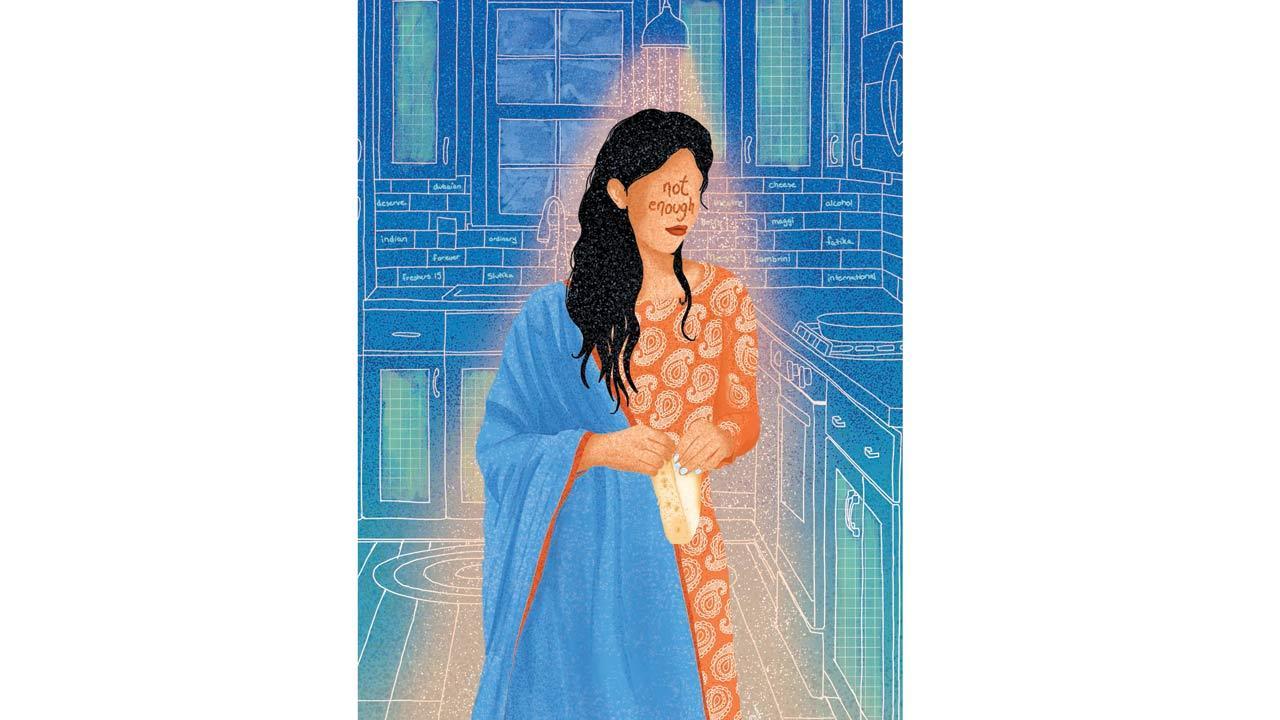

This artwork, titled Not Enough, captures the anxieties of an Indian university student navigating her first year and a shared kitchen in the UK. Unable to cook or proudly embrace her culture, she grapples with a sense of inadequacy and lack of identity. Illustration/Hanifa A Hameed

In 2010, I turned 19 and I knew it was time to leave Dubai and settle abroad. Going to the UK was potentially the beginning of my “forever” story. Who knows, in ten years, I could even have a different passport; the possibilities were endless. Unfortunately for me, there were rumblings that the Tory government would be revoking the post-study work visa for international students fairly soon. Even though I was disheartened, I wasn’t that worried because I had three years. Three full years, to convince this place and everyone in it that I “deserved” to stay here after graduation. How difficult could it be?

ADVERTISEMENT

I was so desperate to find a new home and to fit in, that I was willing to reinvent myself. That’s what university is for, right? Leave behind the “old” you? Normally, this kind of identity crisis is a process of forgetting. People tend to forget who they are and where they came from. The problem with me was that I don’t think I ever had an answer to either question to begin with. As a teenager, it’s normal to still be figuring things out, but I began with such low self-confidence that it almost ran that process into the ground.

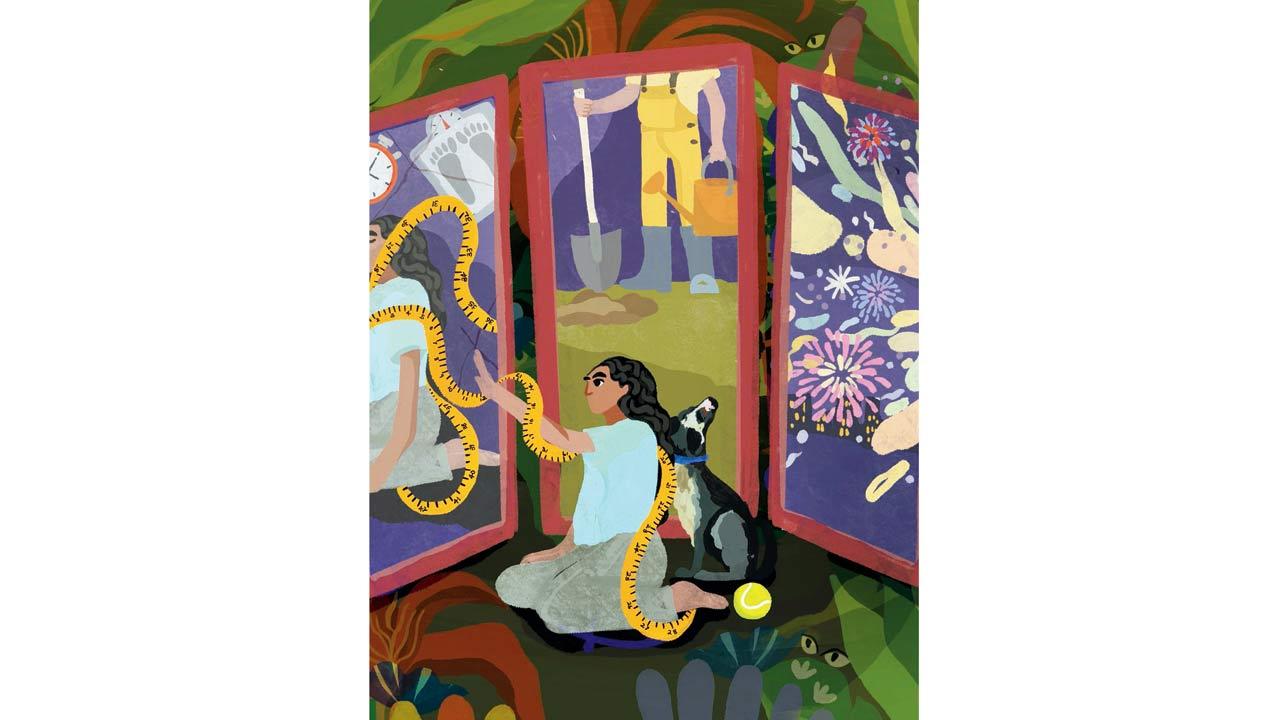

This artwork, Raising the Roof, reflects the anxieties of the author raising themselves and their anxious puppy during the COVID-19 outbreak. Dealing with insecurities and mental health struggles while worrying about projecting their fears onto him, creating a cycle of uncertainty for both of them. Illustration/Tanya Timble

This artwork, Raising the Roof, reflects the anxieties of the author raising themselves and their anxious puppy during the COVID-19 outbreak. Dealing with insecurities and mental health struggles while worrying about projecting their fears onto him, creating a cycle of uncertainty for both of them. Illustration/Tanya Timble

Let’s not even begin to unpack the very loaded question, “Where are you from?” If I said India, people didn’t think I “sounded” or “behaved” like an Indian. If I said Dubai, they would say, “But you don’t look Arab or Dubaian?” Normally, my icebreakers ended up being longer than most as I rambled on about where exactly I was born, where my parents were born, and why I sounded American. It was tricky and exhausting and I found myself constantly trying to justify who I was.

Deep down, I felt ashamed of whatever this version of me was. Not Indian enough, not Arab enough, not “Dubaian” (which, by the way, is not an actual term, no matter how hard people try to make it one) enough. I was self-conscious of this amalgamation of culture; I didn’t quite understand how to use it back then. Yes, I may have been more aware and worldly than most, but I didn’t see it as a strength. I was something else. I sounded different. I acted differently. I was strange. I didn’t fit into a box, which is difficult for people when they’re trying to make fast judgements.

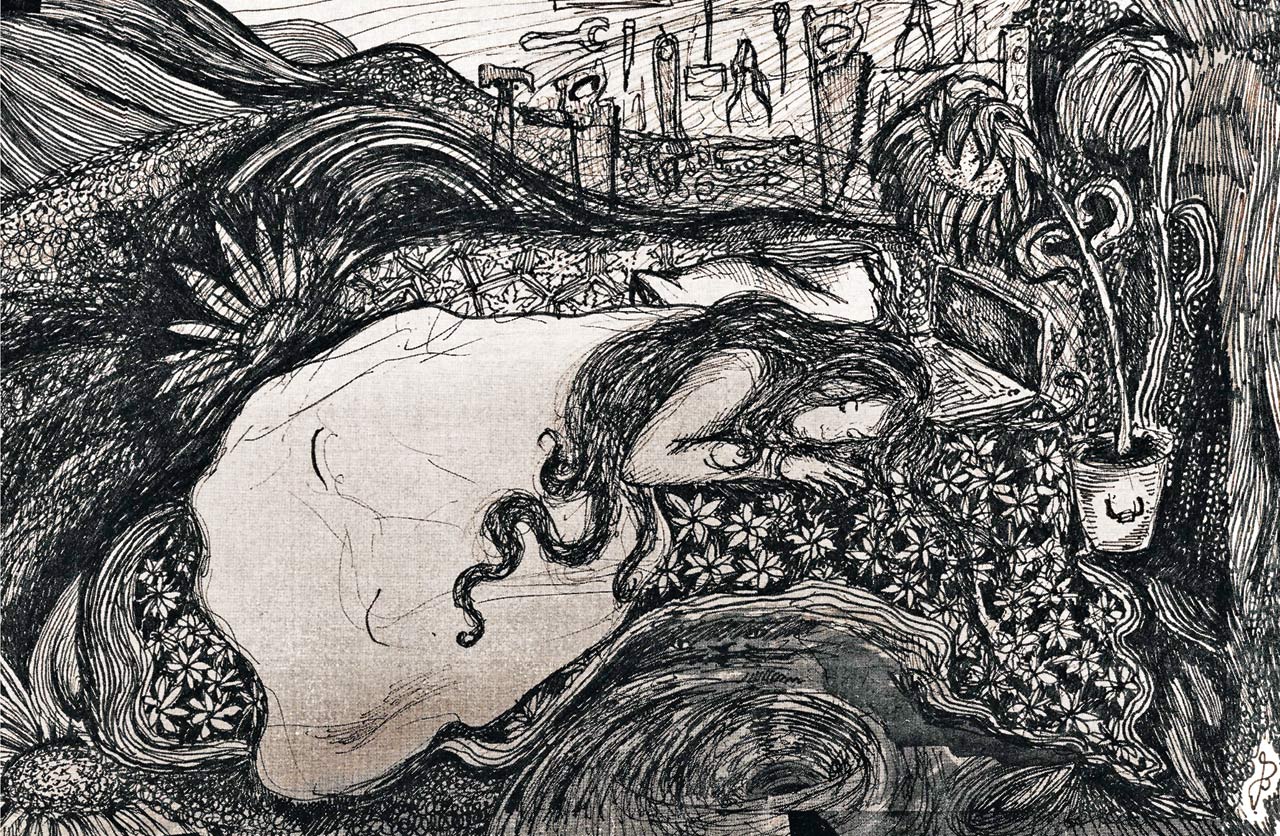

This image, titled HTTP Error 500: Internal Server Error, depicts the author’s despair during her Masters programme. Technological breakdowns threatened her future, hindering her PhD application. It captures the crushing weight of academic failure and the fear of losing her newly found “home” in the UK. Illustration/Annette Fernando

This image, titled HTTP Error 500: Internal Server Error, depicts the author’s despair during her Masters programme. Technological breakdowns threatened her future, hindering her PhD application. It captures the crushing weight of academic failure and the fear of losing her newly found “home” in the UK. Illustration/Annette Fernando

I was more nervous about peoples’ opinions of my looks than anything else. I would worry about my personality later. I was convinced my appearance would be the first thing that would be judged. I was grateful that in high school, I had lost a lot of weight, mostly by not eating, and pining over boys. I thought losing the weight would get me what I wanted and give me the confidence I needed. But the reality is that I was never going to be happy with my body or the size of my face, no matter what number the weighing scale spat out. I was hoping I could hide behind my long, thick fringe which covered most of my face. But it didn’t work. It drew more attention instead, especially when I had massive acne breakouts. There was nowhere to hide.

Why was I putting myself through this? Why did I decide to leave the toxicity and comfort of the people I grew up with in Dubai? With them, I know all their tricks, there’s no new curveball they can throw my way. So what makes me think I can handle similar opinions from new people? I know they will be similar because they’re true: I’m an ugly, chubby, pizza faced pumpkin.

It was my first time away from home, away from my siblings, the first time anyone would see me for me. I wasn’t quite sure how I felt about that. I wasn’t quite sure how to navigate this world, there was no book I could have read and neither of my siblings had done their undergrad abroad. I was lucky and grateful but very alone. It’s not like I could rely on the other child who grew up in Dubai who was going to the University of York and would be in my college. Several times, I was referred to as “exotic”. Apparently, it’s a compliment.

• • •

Soon the kitchen became our place to hang-out but I still hated it when the spotlight was on me. One particularly chilly evening, we were playing Articulate in the kitchen and I was paired up with my UK best friend’s boyfriend/manfriend. He was very smart, posh, arrogant, and kind. I have always hated playing games because people get way too competitive and it makes me uneasy. Also, they will then find out the truth about me which is, ‘I’m not good at anything’ or ‘I’m dumb’. However, I was trying to get into the spirit of things. It was my turn to guess a word that he was describing, it’s safe to say that I had no idea what it was. When he finally told everyone the word that I was supposed to guess, everyone “mmm-ed”, “hmm-ed” and “aaah-ed”. I instantly felt ashamed, red in the face (grateful to be brown) and regretful about leaving my room. My partner was very irritated with me. How could I not know? Had I been living under a rock that had no dictionaries? He finally consoled himself by saying, “You know what, it’s alright. It’s not like English is your first language anyway.” I didn’t know where to look and I didn’t know what to say. Not my first language? It was the only language I knew. But this confirmed my suspicions, I always had doubts about my ability in this language and they were now confirmed. I could no longer say that I was fluent in English on my CV. Everyone just carried on with the game while I could feel the sweat making its way down my back. It felt like I was on fire and sitting on dry ice at the same time. Either way, I was getting burnt. Lesson learnt, next time, I won’t sit next to the radiator, no matter how cold it is. Oh, and never play games.

Excerpted with permission from Citizen by Descent by Kritika Arya, self-published

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!