William Dalrymple’s son, Sam, is carving out his own identity as an upcoming historian. His new book deals with the effect of the Raj on South Asia and the five partitions that reshaped it

Sam Dalrymple’s new book is called Shattered Lands: Five Partitions and the Making of Modern Asia by HarperCollins. Pic/Nishad Alam

If history is destined to be revisited, the young might be best placed to do so. “Our idea of undivided India is basically wrong,” says Sam Dalrymple, 28, as we sit chatting about his upcoming book Shattered Lands: Five Partitions and the Making of Modern Asia in a friend’s drawing room in Defence Colony, Delhi. He shows me a map on his phone. “If you look at what India constituted in the 1920s, it’s far vaster than India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. The ‘Indian empire’, as it was called, extended as far east as what’s now Myanmar and as far west as what’s now Aden in southern Yemen... It included places like Dubai, which were basically princely states.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The story of why Dubai got away, or how Burma was separated, he says, is not something that ever comes into the conversation when you hear about partitions. And yet these divisions have led to major conflicts in the region, such as the Rohingya crisis, which you can trace to the partition of Burma.

Sam, born to India-based Scottish historian William Dalrymple and artist Olivia Fraser, raised in Delhi, is a scholar, writer, multi-media producer and peace activist. In 2018, he co-founded Project Dastaan, a peace-building initiative which connects refugees displaced by the 1947 Partition. But what’s most exciting about this multi-hyphenate is how he is representative of a new wave of diverse and young South Asian historical scholars—like Manu S Pillai (Gods, Guns and Missionaries, False Allies), Anirudh Kanisetti (Lords of the Earth and Sea, Lords of the Deccan), Narayani Basu (VP Menon: The Unsung Architect of Modern India), Vanya Vaidehi Bhargav (Being Hindu, Being Indian), Abhishek Chaudhary (Vajpayee) and Tripurdaman Singh (Sixteen Stormy Days, Nehru: The Debates that Defined India) — whose work is characterised as much by meticulous research as bold, fresh perspectives and nuance and who turn our assumptions about history, and sometimes geography, on their heads.

Sam, born to India-based Scottish historian William Dalrymple and artist Olivia Fraser, raised in Delhi, is a scholar, writer, multi-media producer and peace activist. Pic/Nishad Alam

Sam, born to India-based Scottish historian William Dalrymple and artist Olivia Fraser, raised in Delhi, is a scholar, writer, multi-media producer and peace activist. Pic/Nishad Alam

We may not agree with everything they say or write, but we can’t not be persuaded to read more, and think more deeply than we have before. A defining feature of this wave, which came into existence about a decade ago, is that, without eschewing academic rigour, they write compelling non-fiction, and some scholars from this wave have transformed historical storytelling not just through books but also podcasts, multimedia and social media. Sam Dalrymple is such a scholar.

The “five partitions” of the Shattered Lands are the separation of Burma, the separation of the Arabian states and Aden, the partition of British India and the creation of Pakistan, the Princely States going to one country or the other, thereby determining the modern Indian border, and finally, the creation of Bangladesh. The seed of the book lay in Dalrymple’s encounter with a scholar from the Chakma community in Tripura, who asked him “which partition” he was talking about? “Tripura is one of the states which never gets mentioned in relation to Partition, yet is the only state that’s had a complete demographic transformation as a result of migration from Bangladesh in the wake of partition,” says Dalrymple. Interviewees in Tripura said to him: “We were first affected by the separation of Burma in 1937 which cut off all of our trade from Arakan. Then we were affected by 1947. Then by 1971.”

Notwithstanding Dalrymple’s parentage, his journey into the realm of South Asian historical research was not as expected as it might appear. He had planned to study physics and philosophy. When he didn’t get into his dream university in 2015, he took a gap year in which he worked for a bookstore in London, and then spent money he had earned traveling across Pakistan and India with a friend: “From Jaipur all the way down to Kanyakumari.” This was the first trip he had taken without his family and it culminated in an internship with Turquoise Mountain (a non-profit dedicated to protecting heritage and communities at risk) in Kabul. By this time he had already been learning Farsi for a while, an interest sparked off by a previous visit with his family to Bamyan in Afghanistan. “It was there [in Kabul] that I decided I don’t want to go back to studying Physics,” Dalrymple says. “I knew I wanted to get into something to do with this ‘world’. I wasn’t sure where it would take me. But, with dad as a historian and a whole array of people—from Persian translators to historians and scholars—coming over for dinner, I came from a family where I knew there was a world out there of people who had made a career along such paths.”

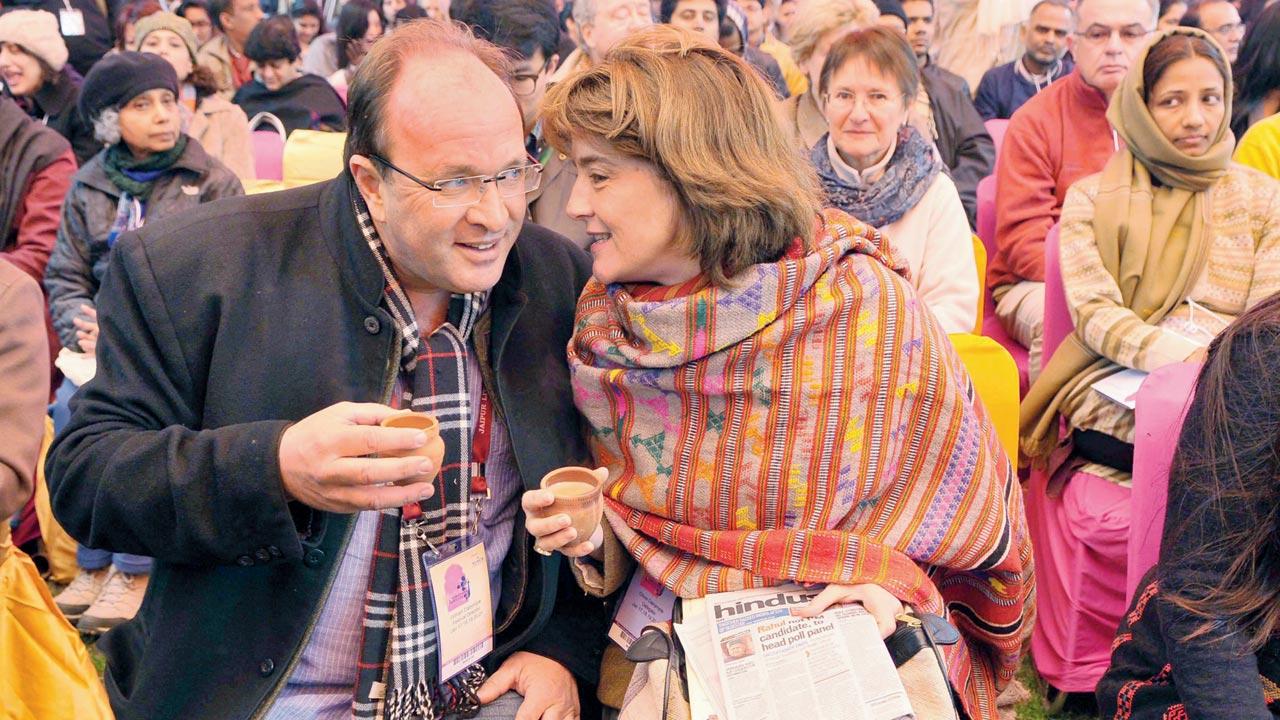

William Dalrymple and Olivia Fraser. Pic/Getty Images

William Dalrymple and Olivia Fraser. Pic/Getty Images

At Oxford he studied Philosophy and Theology, before switching to Sanskrit and Persian after his first year. South Asia has about a quarter of the world’s population, some of the greatest history, art and architecture, believes Dalrymple, and still there’s so much to discover in a way that there isn’t in places in Europe. “Here you will find major necropolises of an entire dynasty sitting encroached upon in a random village which no one has written about. And you can tell just by the look of it that this was once one of the most important things.”

Shattered Lands is a magisterial work for the connections it makes between time and place, linking some of the most tumultuous periods and regions in the history of Asia. Built out of oral histories as well as an impressive sea of primary and secondary source material, what grips you as a reader is a storytelling which switches seamlessly from gripping narrative to the presentation of a piece of historical record, weaving together little moments and big perspectives. If reading about how the history of Dhirubai Ambani and Reliance is inextricably linked with the separation of Aden makes you marvel at how unpredictably the sweep of the past affects the reality of the present, reading about Nehru overhearing Reginald Dyer on a train will make you realise how an unwitting moment can change the course of a life and a nation. You will read about how a Buddhist of Burmese origin became the president of the Hindu Mahasabha and why Lady Mountbatten likened both her husband and Vallabhbhai Patel to gangsters in a letter.

You will read, also, about the lesser known and forgotten—a diary, in Gurmukhi, of Uttam Singh which documents the exodus of a Sikh mining community from Burma to the present-day India, through jungles and rivers. “They celebrate Baisakhi in the jungle, with howls of leopards echoing around them,” Dalrymple says. He recovered the diary from an attic in North London, where Singh’s family now stays. He connected with the family through Uttam Singh’s grandson, who works with the popular Indian restaurant Dishoom, whom he found through Instagram.

Dalrymple, like Pillai and Kanisetti, takes his research as well as storytelling beyond books, to uncover and bring to life lesser known and seemingly unlikely moments from South Asian history on his Instagram and substack—appropriately titled “Travels of Samwise”—as well as a column for the Architectural Digest. His posts include ones on the tomb of the last Ottoman Caliph, “within walking distance of the Ellora Caves”, and what is perhaps the oldest temple in the Delhi region, possibly built by the Pratiharas, but which many in the capital seem unaware of. At a time when history and its politicisation causes so much anxiety, this new wave of remarkable popular history writers arrive as a balm, complicating our narratives, opening up new vistas and worlds with wonder and humility, passion as well as introspection.

Rishi Majumder is co-founder of the digital history project Indian History Collective

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!