A grand exhibition that opens at New York’s Met celebrates ignored Buddhist art of the south, including Maharashtra, shining light on the piece that completes the Indo-Roman trade story

Poseidon (after Lysippos), Alexandrian Roman, 1st century CE, copper alloy, 57/8 × 115/16 × 115/16 in. (15 × 5 × 5 cm), excavated at Brahmapuri in Kolhapur of Satara district, Maharashtra, 1944–45, collection: Town Hall Museum, Kolhapur, Maharashtra; (right) An ivory statuette discovered in the ruins of Pompeii, a Roman city destroyed in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius 79 CE. It was found by Italian scholar Amedeo Maiuri. The yakshi or tree spirit representing fertility is evidence of commercial trade between India and Rome in the first century CE. According to the Naples National Archaeological Museum, it was created in India in the first half of that century. Pic/Getty Images

The understanding of Buddhism as we see it today is a 19th century reinvention, largely premised on scholars who were studying the texts and the core of Buddhist literature—the sutras, jatakas, avadanas—in the abstract as purely religious documents. This, in a sense, detached the understanding of Buddhism from the reality on the ground. They were also focused on the holy sites of the Buddha, i.e., those touched by his presence in his lifetime, from his birth through to his paranirvana or “complete extinction” and therefore, became pilgrimage sites. All of those are located in North India,” John Guy, Florence and Herbert Irving Curator of the Arts of South and Southeast Asia, Department of Asian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met), New York, tells mid-day over a video call.

ADVERTISEMENT

Guy is the curator of Tree and Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India, 200 BCE—400 CE, an exhibition opening at the Met this week, featuring more than 125 objects, including major loans from India, which gives long due recognition to the lesser-known Buddhist art of the Deccan. “I felt it was important to look at the most important surviving intact monuments we have for all early Buddhism. There is Bharhut, Sanchi, the early phase Ajanta, and early phase Amaravati. These are the four greatest surviving monuments we have of early Buddhism in India and they’re all in the South. Nothing approaching them survives in the north, except Sarnath, most of which has been subjected to extensive renovation. And because Buddhism today, has become a global religion, people almost lose its connection with India sometimes. But of course, it is born in India. It is an Indian religion. It originated and was nurtured in India. I wanted to bring that point home very strongly,” he says.

John Guy

John Guy

The publication Tree and Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India accompanies the exhibition and features a catalogue of the items on display, plus essays by Guy and other scholars about pre-Buddhist nature cults, stupas and relic worship, the role of commerce and patronage and India’s international trade with the Roman world. As Guy writes in his Preface, “Much that we need to learn about Buddhist India in the early centuries CE is increasingly recognised as being shaped by the dynamics of global exchange”. He explains that the flourishing of Buddhist art and culture in the south at this time was occurring against the backdrop of the prosperity of the Satavahana kingdom comprising the present-day Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and Maharashtra, which had the advantage of the west coast maritime connections. While there was royal patronage going back to emperor Ashoka, inscriptional evidence suggests that monastic Buddhism and all the great monuments that embodied it were predominantly built on the prosperity of the mercantile communities.

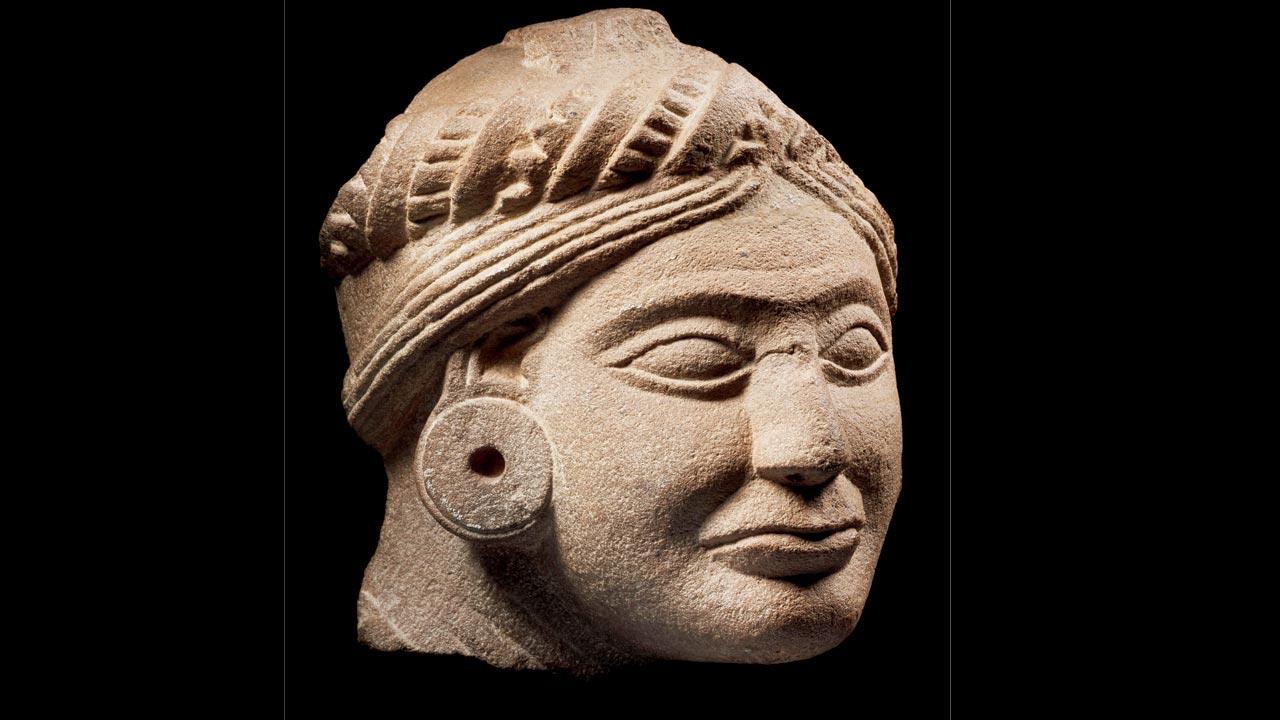

Portrait of a donor, Sarnath, Uttar Pradesh, Maurya, 3rd—2nd century BCE, sandstone, 71/2 × 4 × 6 in. (19.1 × 10.2 × 15.2 cm), collection: National Museum, New Delhi.

Portrait of a donor, Sarnath, Uttar Pradesh, Maurya, 3rd—2nd century BCE, sandstone, 71/2 × 4 × 6 in. (19.1 × 10.2 × 15.2 cm), collection: National Museum, New Delhi.

“The monasteries no longer comprised just small community living spaces, wooden structures or even forest hermit retreats. This is a big institutionalised Buddhism with large complexes and permanent communities, with the stupas, spectacular two-three storey high building equivalents encased in blazing white limestone in the south in a landscape which were otherwise very modest in scale and would’ve been awe inspiring to the local communities,” Guy explains. Almost all the sculptures in the exhibition are directly related to the adornment of the stupa: from the toranas or ceremonial gateways, processional railings to the super structure, evoking a sense of the grandeur of the monuments. “I also try and blow up the idea that monasteries were only quiet places for prolonged periods of meditation and learning. They were also commercial places and lived places where traders, travellers, pilgrim monks and tradesmen came. During festivals, the people came and made a lot of noise with musicians and dancers. We see this in Sanchi. where the celebrations honoring the Buddha resemble melas It’s very explicitly depicted, but the textual scholars have in the past tended to ignore this because it doesn’t fit with the image that emerges from the texts, which have a certain sobriety.”

Ayaka platform panel with the Buddha in meditation venerated by Nagaraja. Mucalinda and his clan Nagarjunakonda, Guntur district, Andhra Pradesh, Iksvaku, late 3rd—4th century CE, limestone, 143/16 × 26 × 913/16 in. (36 × 66 × 25 cm), collection: Archaeological Museum ASI, Nagarjunakonda, AP

Ayaka platform panel with the Buddha in meditation venerated by Nagaraja. Mucalinda and his clan Nagarjunakonda, Guntur district, Andhra Pradesh, Iksvaku, late 3rd—4th century CE, limestone, 143/16 × 26 × 913/16 in. (36 × 66 × 25 cm), collection: Archaeological Museum ASI, Nagarjunakonda, AP

There was also a burgeoning international exchange with the Roman world. Guy speaks of the dynamic trade system between the Mediterranean and the western coast of India where trade in cotton goods, gemstones and ivory was common. There were circulating Roman objects, which included coins with equestrian portraits of Roman emperors, and influences filtering into the art where the lotus flower alternated with the acanthus leaf, a Mediterranean motif. For this exhibition, the government of Maharashtra has lent for the first time the Roman bronzes excavated at Kolhapur at the so-called Brahmapuri excavation of 1944-45, which sit in the Kolhapur Town Hall Museum. They’ll be shown alongside an ivory figurine of a young woman, clearly from the Deccan, excavated in 1934 in Pompeii from a merchant’s house, which has never travelled since the day it was excavated. “We are showing the Kolhapur Roman bronzes, which includes a beautiful diminutive figure of Poseidon alongside the Indian Ivory from Pompeii. It encapsulates the whole Indo-Roman trade story.”

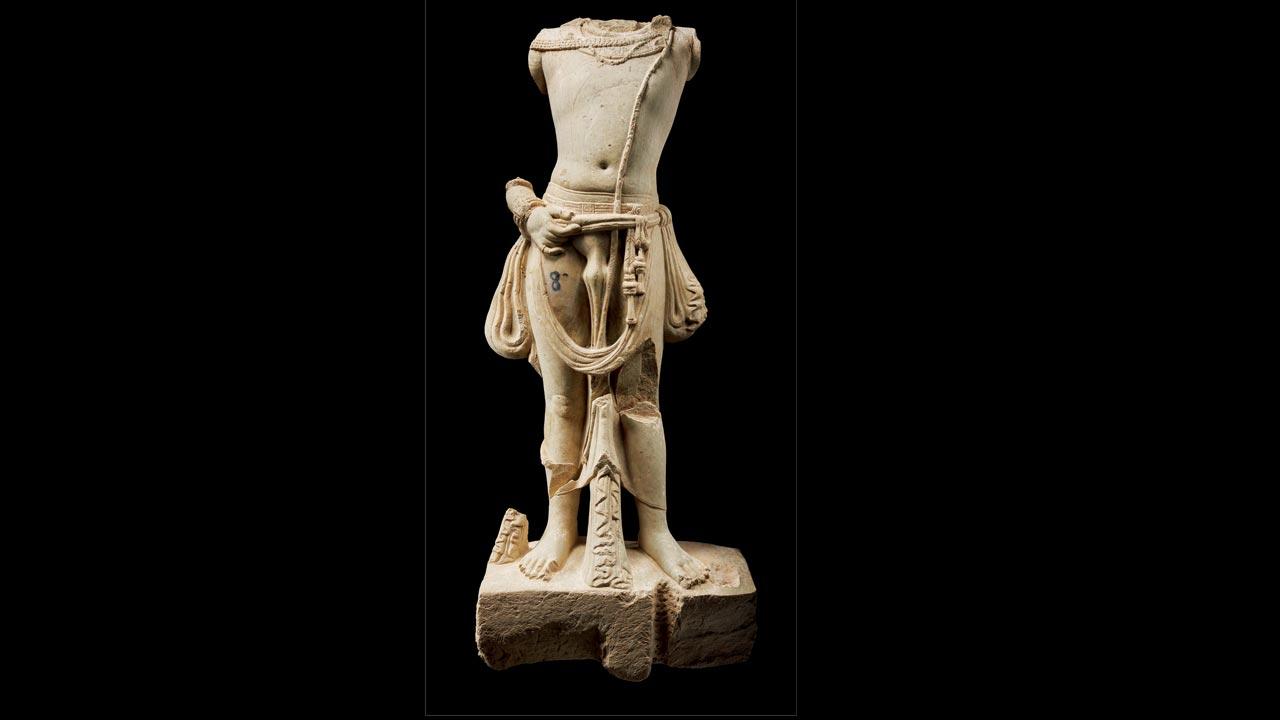

Mahapurusa figure, a yaksa honouring the Buddha Phanigiri, Nalgonda district, Telangana, Iksvaku, 3rd–4th century CE, excavated in courtyard adjoining the apsidal shrines, Phanigiri, 2002—3, limestone, 193 × 100 × 31 cm, collection: Department of Heritage Telangana. Pics Courtesy/Tree and Serpent: Buddhist Art from India by John Guy, Reproduced with permission from Mapin Publishing

Mahapurusa figure, a yaksa honouring the Buddha Phanigiri, Nalgonda district, Telangana, Iksvaku, 3rd–4th century CE, excavated in courtyard adjoining the apsidal shrines, Phanigiri, 2002—3, limestone, 193 × 100 × 31 cm, collection: Department of Heritage Telangana. Pics Courtesy/Tree and Serpent: Buddhist Art from India by John Guy, Reproduced with permission from Mapin Publishing

The earliest Buddhist imagery, Guy explains, didn’t represent the Buddha anthropomorphically, but were iconic representations like footprints (buddhapada) the wheel, the riderless horse, the umbrella and the empty throne. “The exhibition traces that process so that its climax is the fully revealed Buddha. Thus, it takes us from 200 BCE through to 400 CE to capture the emergence of Buddhist art as we know it.” A factor that contributed to the stylistic distinctiveness of the South, Guy tells us, was the important role of nature, nature spirits, cults, and deities of yakshas, yakshis, nagas and naginis, which populated the landscape that the Buddha was born into and was especially strong in the South. The Yaksha cult imagery, he explains, is the earliest known figurative imagery in India, which provided the means by which sculptors could then turn their hand to Buddhist imagery. “These spectacular two-metre high monumental yaksha figures from the third, second centuries, BCE became the prototypes for the early standing Buddhas.” The wish fulfilling tree is also an ancient motif depicted on the Barhut railings and in Sanchi. “Almost every seminal moment of the Buddha’s life is linked to trees, from his mother clutching a tree branch in a sala grove in Lumbini where he was born to his death when he was again, in a sala tree grove and cremated on fragrant wood timbers. So the power of the tree is enormous and continues with the Buddhist bodhi tree sapling planted in every monastery ground.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!