The Chinese in Mumbai are Indian Chinese, not Chinese Chinese. Lunch is chapati bhaaji, not soup. The city’s last few members of the Jewish and Chinese communities talk assimilation and contradiction

In Bombay, the Bene Israelis and Sephardic Jews joined forces, and the latter served as teachers in many schools in the city. Bene Israel teachers of the Free Church of Scotland’s Mission School and the Jewish English School in Bombay, late 19th century, William Johnson and William Henderson. Pic/ Sarmaya Arts Foundation

My Marathi is better than my Chinese,” says Dr Liang-Shun Ma at his clinic in Vashi, Navi Mumbai. “In fact, when I go to any government office, I write my name down in Marathi on a piece of paper and give it to the officials. It’s easier to pronounce this way.” Dr Ma’s family has been in India for three generations.

ADVERTISEMENT

Unlike most communities migrating to then Bombay, the Chinese came by land from Calcutta. They had been migrating to West Bengal since the late 1700s for trade in tea, sugar and other essentials. The East India Company was trying to get a foothold in markets to the east of India, and eagerly helped Chinese businessmen such as Tong Atchew procure land in return for tea and expertise to run plantations in the Northeast. Atchew is said to have started the first sugar mill in India, bringing 1,100 workers with him. According to urban legend, this gave sugar its Hindi word: Chini.

The Shaar Ha Rahamim synagogue was built in 1796 by Samuel Ezekiel Divekar, after he escaped unscathed as a prisoner of war in the second Mysore War. Pic/ Sifra Lentin’s personal archive

Soon, a China Town was established in Calcutta, and it flourished while the city was the capital of the Crown. As Bombay grew in industry and prosperity, many of the community made their way here. “My great grandfather came via Burma, I think,” says Tung Shang Chen, adding with a laugh, “My mother, from Kalyan. My grandparents were nomads, trying to settle in Africa, Saudi Arabia and England, but finally came back to India.”

In the 1950s and 1960s, for those living between Mazagaon and Colaba—the choice of hairdresser and dentist would have to be Chinese. This area covered the major hubs of occupation, Mazagaon and Byculla with their proximity to the docks, and Colaba to the centre of British life, Fort.

Bene Israeli Jews touch the Mezuzah—a piece of parchment containing Jewish prayers—as they leave the Magen Hassidim synagogue during Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year. Pic/Pal Pillai/AFP via Getty Images

Bene Israeli Jews touch the Mezuzah—a piece of parchment containing Jewish prayers—as they leave the Magen Hassidim synagogue during Rosh Hashana, the Jewish New Year. Pic/Pal Pillai/AFP via Getty Images

“We are skillful with our hands,” says Dr Ma, who started assisting his father, also a dentist, while in college. “So, the Chinese worked as carpenters, dentists, hairdressers, and cobblers in workshops in Mazagaon. They made paper flowers and lanterns, and sold them outside Crawford Market.” In the lane behind the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, now dotted with curio shops, sat Chinese cobblers. The height of sophistication was to have bespoke shoes, made in the same luxurious fabric as the outfit, cobbled in Cheena Gully. From the 1940s to ’60s, a sizeable Chinatown flourished near Kamathipura, and a community centre existed at Grant Road.

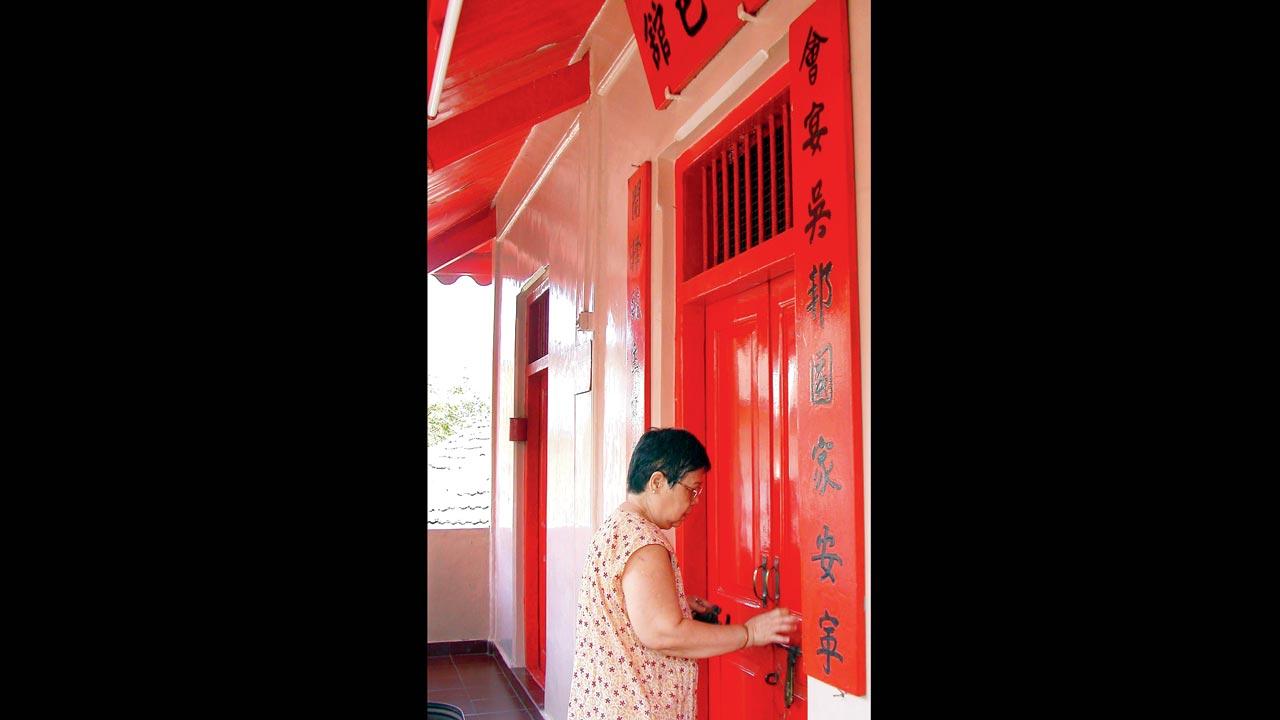

The red-doored Chinese temple to the warrior god Kwan Kung in Mazagaon was the community’s centre. Only four families live in the lane now; and there is no priest. A caretaker comes every Sunday to clean the shrine.

Leora Micah Joseph’s great great grandfather Subedar Major Ezekiel Haeem Talkar and great great grandfather Aaron Ezekiel were both in the military. Pics/Sayyed Sameer Abedi

Leora Micah Joseph’s great great grandfather Subedar Major Ezekiel Haeem Talkar and great great grandfather Aaron Ezekiel were both in the military. Pics/Sayyed Sameer Abedi

In many ways, Dr Ma, Chen and others of the community are Chinese impersonators, more Indian than Chinese. “We eat chapati-bhaaji at home,” laughs Dr Ma. “And my Marathi is better than my Chinese. My parents tried to teach me, so I know a bit.” Occasionally, a soup makes it to the dining table in the Ma and Chen household.

Dr Ma has Chinese characters on the wall of his clinic and small shrines to various gods and goddesses, between whom sits a Ganesha. “My mother told me to put up the characters; they mean ‘Shubh-Labh’ in Chinese. Our cultures are very similar.” Next to his table is Kwai Ian, the Chinese goddess of prosperity; or “our Lakshmi,” as Dr Ma says.

With no religious head, they have been winging it at festivals most of the time. On Chinese New Year, which falls towards the end of January and beginning of February as per the lunar calendar, they throng to the Mazagaon temple, light incense and burn paper money as offerings. The traditional dragon dance is still performed. “We also go to pay our respects to our ancestors at the cemetery on Antop Hill,” says 63-year-old Chen, “And on our version of All Souls Day, something like pitrupaksh.” Burials are also a ceremony of rituals stitched together based on who knows what; mostly a simple prayer and an incense stick suffice. Weddings are usually at the registrar.

Sifra Lentin’s family name was Pingle, indicating they came from the village of Pinglesai. Pic/Sameer Markande

Sifra Lentin’s family name was Pingle, indicating they came from the village of Pinglesai. Pic/Sameer Markande

So, it’s hard to imagine that Colaba lit up and was dressed for the Chinese New Year just a few decades ago. Tham’s beauty salon, and restaurants such as Kamling, Hong Kong and Nanking were centres of glamour. “My father was the only one in the family to read and write Mandarin,” says Chen, who grew up in Grant Road. “He studied in the Chinese school near Agripada. We used to have a ground too for community activities. Now there’s only the Maharashtra Chinese Association that looks after the cemetery.”

The Chinese are the quiet, plodding type. “We work hard and keep a low profile,” says Dr Ma, “and don’t have any rules about marriage. My wife is from Patna—she had a Chinese grandfather—and she follows all the Hindu pujas and rituals. I went to my sister’s home for rakhi earlier this year.” Chen’s maternal uncle schooled in Kalyan, and knew Sanskrit and Marathi.

The Chinese cemetery on Antop Hill has most footfall on their new year and the Chinese version of All Souls’ day, when the community pays its respect to ancestors. Pic/Sameer Markande

The Chinese cemetery on Antop Hill has most footfall on their new year and the Chinese version of All Souls’ day, when the community pays its respect to ancestors. Pic/Sameer Markande

The community became even quieter in 1962, during the Indo-China war. “It was an atmosphere of fear,” says Dr Ma. “Those without papers were rounded up and sent to camps in Rajasthan. They didn’t know where to go. My father had done all our paperwork, so we were safe. I was born in India; I am Indian.” If repatriated to China, it would mean going to a foreign land. Every person we spoke to—most Indo-Chinese come from Hubei province and speak Hubei—had never been to China, nor had any family there.

Fahshing Liao’s parents came from China to Calcutta, and he moved to Mumbai when he was in his early 20s in search of a job. “My naani kept the eldest of my siblings, a boy, back with her in Hubei to help with the fields,” says Liao, who is most comfortable speaking Hindi, and also speaks Gujarati and Bengali, but only a smattering of Chinese. His children don’t know it at all. “There are no elders in the house to teach them,” says the chef who has worked in Sweden, Bahrain, Cypress, Dubai, and Saudi Arabia after learning to handle the wok in the now-closed Flora Chinese Restaurant, Worli.

The Kwan Kung temple in Mazagaon is still the centre of celebrations for Chinese New Year, though there is no longer a priest there. File Pic

The Kwan Kung temple in Mazagaon is still the centre of celebrations for Chinese New Year, though there is no longer a priest there. File Pic

In Chen’s family, his father was the last torchbearer. “He made a calendar predicting when the Chinese New Year would fall for the next 100 years,” says Chen, whose wife’s mother is Sikkimese. “He also gave name options for descendants; he named my children too.”

The name is perhaps the only thread linking the Chens to mainland China. They have no rules against inter-marriage, and Gujarati and Marathi spouses are common. The only concession they make is to choose simpler names that can be pronounced easily. Dr Ma’s son is called Lishu, translating to ‘tree of prosperity’”, and his daughter is Yuli, meaning ‘beautiful jade’. Chen’s children are Pen Shen and Ju Ling.

Dr Liang-Shun Ma’s Clinic in Vashi has the Chinese symbols for prosperity, and Kwai Ian, the Chinese ‘Lakshmi’. Pic/Sameer Markande

Dr Liang-Shun Ma’s Clinic in Vashi has the Chinese symbols for prosperity, and Kwai Ian, the Chinese ‘Lakshmi’. Pic/Sameer Markande

“Our names give us continuity; it tells us who our closest relatives are and the larger family,” explains Chen. “All siblings have the same middle-name [Shang for his brothers, and Ling for sisters]. It indicates whether you are a girl or a boy. Chen is the larger family name; I cannot marry a Chen.”

Post the Indo-China war and closer to the 1990s, most of Bombay’s [Chinese] population migrated to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and other fields of gold. “But even there, we are Indian Chinese and not Chinese Chinese,” Dr Ma explains. “We are a separate community and usually prefer to marry each other.” Chen assumes there would be about 150 people still living in Mumbai; Dr Ma guesses there are four families in Navi Mumbai, one of which is Chen’s.

“This will be the last generation here,” says Chen. When asked why he didn’t migrate, he says, “We have become so Indian in habit and culture, we’ll feel out of place anywhere else.” Dr Ma also tried out Canada, but it did not fit. “This is my janmabhoomi and my karmabhoomi,” he says.

“I cannot separate my Indian identity from my religious one,” says Leora Joseph née Ezekiel. “I am Indian first, and Jew later.” Ezekiel is a surname with a legacy in Bombay. There’s the celebrated poet, actor, playwright, editor and art critic Nissim Ezekiel, who incidentally taught Leora American Literature in Mumbai University. He was her father’s uncle. But the family, like many Bene Israelis, has a military history that stretches all the way to the Afghan War in the late 1800s.

The Bene Israelis also migrated to Bombay over land, but from nearby Konkan. “As per oral history,” says Sifra Lentin, Bombay History Fellow, Gateway House, “our ancestors were shipwrecked just south of Bombay islands and only seven men and seven women survived. The dead were buried under two mounds on Navgaon beach, close to Alibaug, and a memorial stands there now.”

Lentin believes this could have been a trading ship, and that the group was marooned sometime before 70 CE. Those shipwrecked assimilated into the Konkan cultural landscape, speaking Marathi, wearing a nauvari saree and observing many traditions.

Religiously, they observed the weekly Sabbath, maintained a kosher diet—no mixing of milk with meat, eating only fish with scales, meat slaughtered as per Kosher laws, and abstaining from eating any animal with a cloven hoof, such as pig; and crustaceans and fish without scales. “Out of respect for Hindus,” says Leora, “unlike other Jews, Bene Israelis in India don’t eat beef.” Most of them worked as oil-pressers, and were called Shaniwar Tellis since they didn’t work on Saturdays. Eventually, they created last names by suffixing the Marathi ‘kar’ to the village they came from. Leora’s family were Talkars from the village of Tal, until they took up the name of her great, great grandfather, Ezekiel Haeem Talkar. Her husband’s family name is Dighokar from the village of Dighodi. Then there is the famous naturalist Isaac Kehimkar, better known as India’s butterfly man. Lentin is Pingle on her father’s side from the village of Pinglesai; her mother is Mendrekar from a village in Janjira.

The Benes were disconnected from the Jewish community in Cochin by distance, and from the Baghdadi Jews by time. They were discovered by Baghdadi traders in the 10th century, who docked at Chaul port in Raigad. They recognised that the group observed Jewish customs and holidays, but did not possess the holy Sefer Torah books. Slowly, the Cochin Jewish traders nurtured their religious revival as they travelled to and from ports in North Konkan. With the British came Protestant missionaries such as Dr John Wilson, who taught the community to read Hebrew.

There was no need to travel to Bombay yet, until the Portuguese went (taking with them their zest for conversion), and the East India Company began building Bombay up as an economic centre.

“Most Bene Israeli families have a proud military history,” says Lentin. “They fought in the armies of rulers such as Shivaji, the Peshwas, and the Nawab of Murud-Janjira.” In the second Mysore War of 1780-84 between the East India Company and Tipu Sultan, Samuel Ezekiel Divekar and his brother Isaac (both were colloquially known as Samaji and Isaaji) were taken as prisoners of war. They were part of the Sixth Maratha Light Infantry.

“Legend has it that Tipu Sultan’s mother saw them praying,” says Leora, “and told her son not to harm them as they were also People of the Book [the first testament]. Samuel had taken a vow to build a synagogue if they escaped unharmed.” And that’s how Bombay got its first synagogue in 1796 the Shaar Ha Rahamim (Gate of Mercy) on Samuel Street at Masjid Bunder, named after him. “In fact, Masjid Bunder is named after the synagogue,” informs Leora. “In Marathi, a synagogue is called Mashid. ‘Mi mashidi jato’, one would say. That became ‘Masjid’.”

In Bombay, the Benes were able to join forces with more affluent Jews such as the Baghdadis. They worked in the mills, and taught in their schools. They also set up the Sir Elly Kadoorie School in Mazagaon, whose language of instruction was, and still is, Marathi. But serving in the military remained the preferred profession. “Vice Admiral BA Samson headed India’s Western Fleet during the 1965 India-Pakistan War, then there’s Major General Joe Samson,” says Lentin. “My great grandfather Aaron Ezekiel fought for the British army in WWI in Burma,” says Leora, “and Subedar major Haeem Talkar fought on the British side in the Afghan war.”

Other illustrious Benes include actor David Cheulkar, Samuel Israel (former director of National Book Trust), Mayor of Bombay Dr E Moses, Bharat Natyam exponent Leela Samson, and the artist and author Esther David.

Since the end of World War II, many of the youth of the community have made ‘Aaliyah’ (homecoming ) to Israel as it built a Jewish state absorbing the scattered diaspora. “My bosses urged me to go,” says Leora, “They assured me my job would be waiting for me if I didn’t like it there. I lived on a kibbutz, studied Hebrew, travelled within Israel and loved the country, but India is home. Indian Jews, because of living with so many communities for so long, have a wider perspective. My husband and I consider ourselves very fortunate to be born in India.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!