Journalist-author Sam Miller’s book on migration looks at its centrality in human history and aims to reposition modern discussions around it

Migrants queue up at a railway station in Mumbai to leave the city ahead of a lockdown to slow the spread of COVID-19 in April, 2021. Pic/Getty Images

One damp October morning in 2018, I spent 25 minutes in my father’s old study spitting into a small plastic tube,” begins a chapter in Sam Miller’s Migrants: The Story of Us All (Abacus, R899), in which Miller, a London-born former BBC journalist and author who has lived and worked in several countries across Africa and Asia, including India, reflects on his lifelong penchant for a nomadic way of life. “[I]t feels elemental, as if a desire to be on the move, to travel to new places, to be with people who are not like me is part of my being,” he contemplates. Curious about his own desire to keep moving and intrigued by the workings of a “curiosity” gene, an ancient genetic mutation known as DRD4-7R present in all human populations, and among some genetic markers scientifically correlated to how far particular groups travelled from Africa in prehistoric migration, he writes about his decision to test his DNA. This rumination forms a part of one of the book’s several ‘intermissions’ —sections where Miller weaves more personal travel stories about expats and the Passport Index with the book’s larger historical narratives of migration. “It’s something I use in all my books, and they enable me to break with the normal constraints of narrative non-fiction. It’s liberating,” he tells mid-day over an email interview. “Here, it enables me to reflect on my own migration experiences, as well as incorporate the stories of others into the narrative.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The book’s main focus however, is the importance of migration to the human story, a matter that Miller contends has become a modern proxy for other issues affecting our lives and thought such as identity, religion, home, multiculturalism, integration, racism and terrorism. Hence the book, he proclaims, is his attempt “to restore migration to the heart of the human story”, to challenge the way it has been overlooked or misunderstood in history and reposition both the dominant view about migrants and the modern discussions around migration. “It’s a subject that I’ve been interested in for a long time,” he says, his work alongside migrants in different countries over the years having proved influential. “I felt there was very little honest discussion about it in most countries–and very little recognition of how fundamentally migratory we humans are as a species. In the Indian context, it’s a subject that came up in my first book, Delhi: Adventures in a Megacity, and my encounters with Bangladeshi migrants who felt they had to disguise their place of origins, even though they were living alongside—and sometimes married to—migrants who came from West Bengal.”

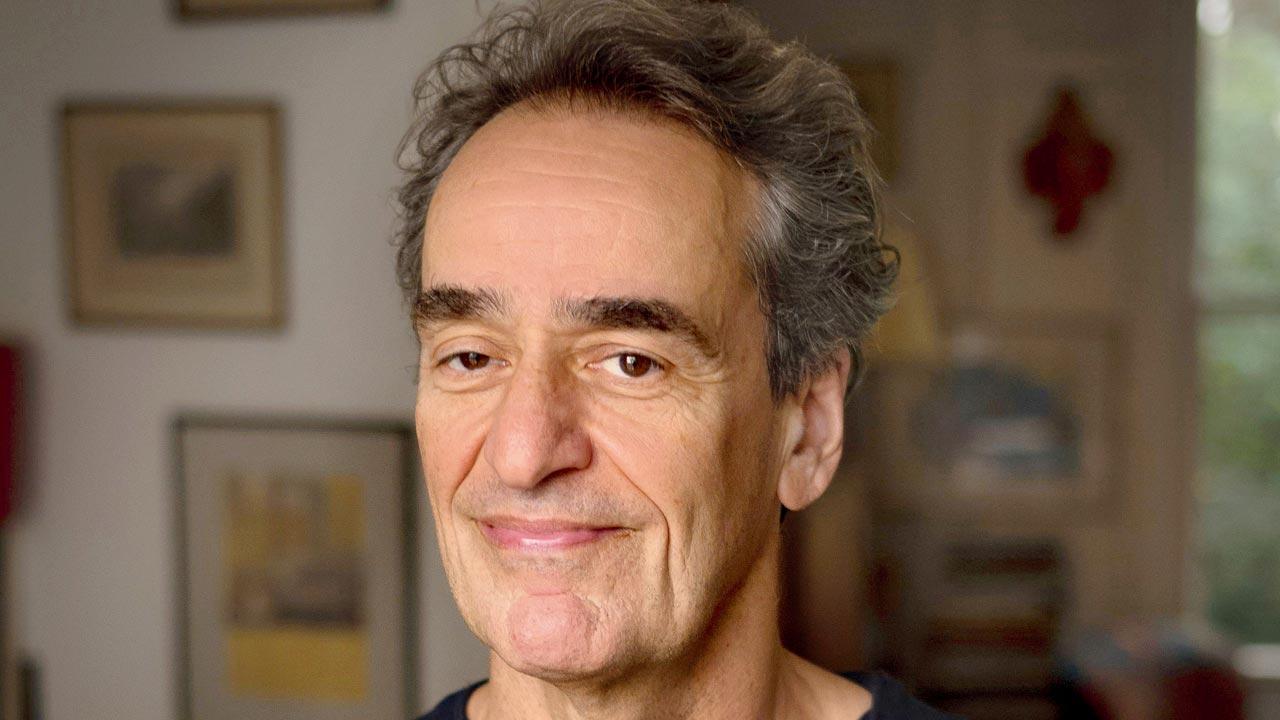

Sam Miller

Sam Miller

Miller’s book charts an ambitious course, starting with the long-extinct ‘lobsterpedes’, creatures that because of their symbolic passage from the ocean to the land about 530 million years ago, could be effectively considered the first migrants. It’s a move so significant that Miller calls it “the lobster equivalent of humans landing on the moon”. From the early travels of the Yaghan who journeyed to the southernmost tip of South America, the Bible which “can be read as a migration handbook” and Alexander the Great who spent most of his adult life on the move, to the origins of the Aryans, the Viking migration, Columbus “whose Atlantic wanderings would ultimately lead to possibly the greatest of all modern human migrations”, the North American slave trade and migration around the South China Sea which was at the heart of what became known as the ‘Maritime Silk Road’, several migratory narratives are examined. The book however stops short of engaging with narratives, patterns and issues around modern migration. “It was a deliberate decision – taken after much thought,” Miller explains. “Modern migration has become such an explosively toxic issue… In most countries people calm down, and talk less emotively, when the discussion is about migration in the past.”

Among several topical discussions in the book is one about the complex relationship between human mobility and contagious disease and how migrants suffer disproportionately during pandemics, calling to mind the much-politicised plight of Indian migrant workers back in 2021. Miller points out that rather than economic migrants or refugees, history shows that it is those trying to avoid getting infected by fleeing who end up spreading contagion. Moreover, “encouraging people to return—in an unplanned manner—to their home villages at the time of a pandemic is a certain way of spreading the virus”.

Miller also writes about how in India where he spent over a decade, migration plays an important role in the struggle over the identity of modern India and the disagreements that are there about that identity. “I used to joke that in India you could make a reasonably reliable prediction of someone’s political views by asking them about migration and the Indus Valley Civilisation. Only in India could you make such a prediction based on such ancient history,” he says. At the same time, he admits that migration is enormously complex in the context of the country. “I would argue that India is, in many but not all circumstances, better considered a continent, rather than just a country. This is particularly relevant to internal migration because India is comparable in scale and population and variety and languages and ‘regional’ identities to Europe, rather than, say, Britain or France. And this applies strongly to the subject of India’s migration history which should be seen through a continental lens.” While India has recently been aping western concepts of what a country should be, other countries, he says, could learn from how it, at least until recently, has been a place where diversity could thrive, “always imperfectly, but still in a more impressive manner than in many other parts of the world.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!