Prolonged grief that stems from the loss of a loved one has now been included as a disorder in the bible of psychiatry, but will it come in the way of mourning or make it acceptable to seek help?

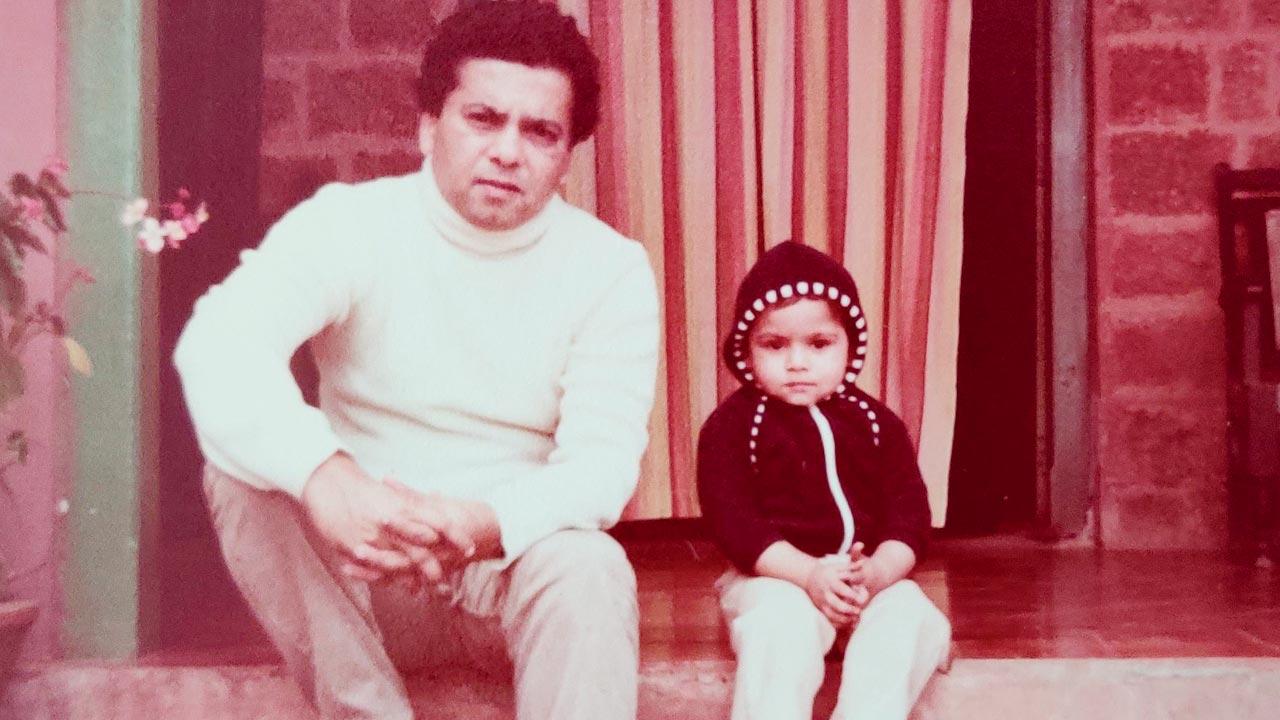

Books blogger Siddhi Palande says she was unable to cope with the untimely death of her father six years ago, due to which she wasn’t able to look after her newborn. “I wasn’t the mother I should I have been to her. I regret this—all I can remember was slipping in and out of this black hole.” Pic/Sameer Markande

I felt like I was inside a dark tunnel, which kept sucking me in, and there was no light at the end of it. Even if there was one, I couldn’t see it then,” says Kandivli-based books blogger Siddhi Palande, while talking about a bleak moment in her life, from six years ago, right after she lost her father, who was all of 55. His passing away, she says, was unexpected. It was her birthday, and she’d just become a mother. “My daughter was six days old, when I lost him. There had been nothing seriously wrong, except that he was anemic,” she shares. Her dad, a politician, was a voracious reader like her. “We were extremely close. He influenced my reading habits, and would recommend books to me. I remember when I wanted to read something, I’d go and sit next to his chair. There were so many questions I’d have for him.” The loss was aggravated because she wasn’t allowed to see him at the hospital, as she was a new mum. “It hit me hard. My body stopped functioning and I wasn’t producing any milk [for my newborn]. I remember that day [of his passing] clearly: my daughter was wailing nonstop, and there was nothing I could do. Someone had to feed her boiled milk.” The next two years were a blur. “A part of me had died, and I didn’t think I would survive this at all. People around me thought I was going crazy, and that I needed to be checked into an asylum. Nobody could understand what I was going through. Somehow books came to my rescue, and helped with the healing.”

ADVERTISEMENT

It was only two years ago, four years after her father’s death that Palande sought help from a psychiatrist. “I was still grappling with insomnia, and suffering from anger bouts.” Palande was diagnosed with post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). “That’s when the treatment began.”

Rohit George, 29, says his mother’s death to cancer triggered mental health issues. “I didn’t know it until then, but I had been living with a lot of anxiety. And that spiralled, when she passed away.” Pic/Anurag Ahire

Rohit George, 29, says his mother’s death to cancer triggered mental health issues. “I didn’t know it until then, but I had been living with a lot of anxiety. And that spiralled, when she passed away.” Pic/Anurag Ahire

Looking back, Palande, who is still grieving the loss of her father, feels guilty about not being there for her daughter. “I wasn’t the mother I should I have been to her. I regret this—all I can remember was slipping in and out of this black hole, feeling angry and constantly breaking down. I think I am trying to compensate for it, probably even over compensate,” she says, adding, “It’s worse when nobody can understand what you are going through.”

Grieving the loss of a loved one has up until now, been seen as a natural response to coping. But a recent development in the field of psychiatry has turned this idea on its head. In March, the American Psychiatric Association, following years of deliberation and arguments, added “prolonged grief” as a disorder in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), referred to as the “bible” of psychiatry. With this development, medicos in the US can now bill insurance companies for treating people with the condition. It will also make way for more research into treatments and medication specifically directed to treat prolonged grief.

Holly G Prigerson, Dr Kersi Chavda and Malvika Fernandes

Holly G Prigerson, Dr Kersi Chavda and Malvika Fernandes

The controversial addition, however, has left many stumped. Psychiatric epidemiologist Holly G Prigerson, who led investigations justifying the inclusion of PGD in International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11) and DSM-5-TR, has had to contend with criticism, both from the outside as well as among her peers. In an email interview to mid-day, she says, “The public outrage is because they misconstrue the diagnosis as pathologising grief, and love and closeness to others. What they don’t appreciate is how rare this disorder is and how impaired those who have it are.”

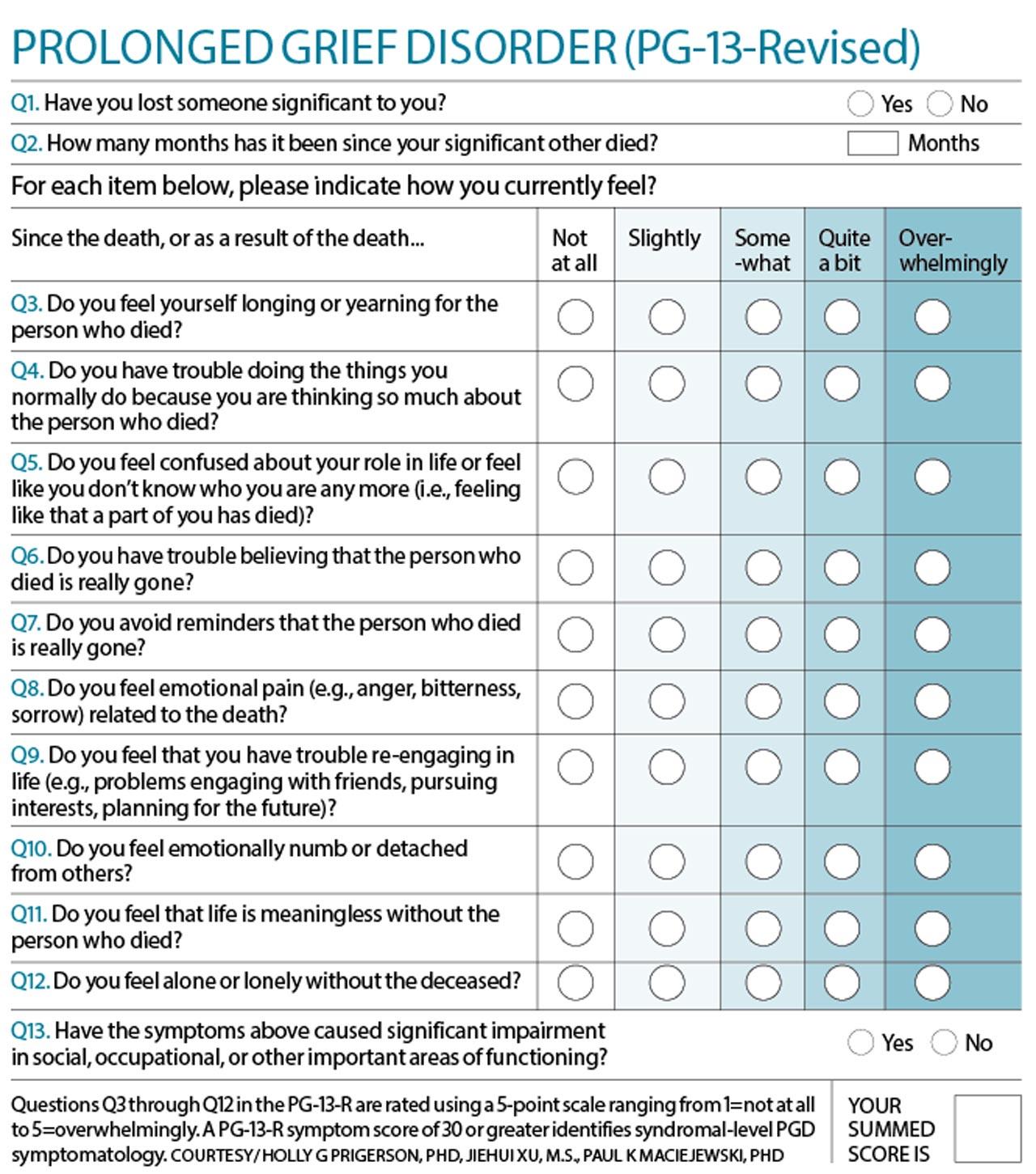

PGD applies to those incapacitated for over a year (in the case of adults) or six months (for children), following the loss of a loved one. The grief response is usually characterised by intense yearning or longing for the deceased and preoccupation with thoughts and memories of the deceased. The grieving person should have at least three of the eight symptoms: identity disruption, disbelief, avoidance of reminders that the person is dead, intense emotional pain, emotional numbness, difficulty with reintegration into life after the death, feeling that life is meaningless, and intense loneliness. “[In some cases] the loss of something cherished and self-defining can trigger PGD,” says Prigerson.

PR professional Mansi Shah, who lost her 43-day-old son in 2015, feels that recognising prolonged grief as a disorder will go a long in validating experiences like hers

PR professional Mansi Shah, who lost her 43-day-old son in 2015, feels that recognising prolonged grief as a disorder will go a long in validating experiences like hers

Her enquiry on the subject began when she started noticing “that symptoms of grief were not responding to treatments for bereavement related depression”. “I then set out to understand if grief symptoms were distinguishable from those of bereavement-related depression, anxiety and trauma, and they were clearly,” she says. “Then the question became, ‘why does it matter?’ Does intense unresolved grief prove distressing and disabling apart from symptoms of depression and anxiety? We learned that intense, severe grief is among the most disabling consequences of loss, a strong predictor of suicidal ideation and even high blood pressure, heart attacks and cancer. This seemed worth understanding better and figuring out how to help those struggling with the loss of a loved one,” adds Prigerson, who is the Irving Sherwood Wright Professor of Geriatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine (WCM), and Co-Director, Cornell Center for Research on End-of-Life Care.

Research by her team, she says, was conducted worldwide from mourners of disparate backgrounds—nationally and culturally, ethnically and racially and religiously. The study also included varied causes of death from cancer to COVID-19, dementia to disasters. “The results have proved generalisable across losses.” She feels that the “massive loss of life from the pandemic and wars such as now in the Ukraine have made the issue of grief ubiquitous”.

Mumbai resident Nikhil Gonsalves lost his father Lancelot in January this year. His grief, however, began much before, when he learnt about his father’s condition in March 2020. “I realised that grief never leaves, it sits with you... It changes you.” Nikhil is seen here with his father at Race View Hotel, Mahableshwar, circa 1986

Mumbai resident Nikhil Gonsalves lost his father Lancelot in January this year. His grief, however, began much before, when he learnt about his father’s condition in March 2020. “I realised that grief never leaves, it sits with you... It changes you.” Nikhil is seen here with his father at Race View Hotel, Mahableshwar, circa 1986

The last 18 months have been the most trying phase for writer and stand-up comedian Rohit George. George, 29, who lives with cerebral palsy, says his life lost meaning the day he learnt that this mother had only a few months to live. “She was diagnosed with a rare form of stomach cancer in November 2020, in the middle of the pandemic. It has no symptoms, and is usually only diagnosed in the third stage. Hers had spread at the speed of light. My dad and sister [who lives in the US] immediately moved her to Kerala, where treatment began.” George was told about the seriousness of her condition in February 2021, when things took a turn for the worse. “I think my family kept it away from me, because I was closest to her. She was my support system.”

When he looks back at his journey of grief, he says his came in two parts. “It began with me preparing to lose her, which is a very hard to do. You can never really come to accept such an eventuality.” The permanence of the loss struck him, when she died in May last year. “Mum helped me cope with my disability, so losing that support was hard. I depended on her for everything, mentally and physically, and for my overall wellbeing.”

Her loss, he says, triggered a series of mental health issues. “I didn’t know it until then, but I had been living with a lot of anxiety. And that spiralled, when she passed away. Now, I feel like a ship without an anchor.” George has been in therapy since. “I have been talking to my psychologist almost every week. It has helped give vent to my emotions. And fortunately, it has not affected my everyday functioning. But I feel that loss of a companion, which she was to me, every single day,” says George, who currently lives solo in Andheri.

The most commonly referred theory on grief was developed by psychiatrist Elisabeth Kubbler-Ross. According to her model, those experiencing grief go through five stages—denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Mumbai resident Nikhil Gonsalves confesses to having felt all, “but for most part, you are plain numb”. Gonsalves lost his father Lancelot in January this year. But his grief, like George’s, began much before, when he learnt about his father’s condition in March 2020. His dad was diagnosed with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), which quickly escalated to a full-blown aggressive form of leukemia. “The literature [on MDS] was little, but scary,” he says, which only added to the uncertainty about his father’s condition. “My grief came at different moments. For most part, I had to put up a brave face for my mum and dad [too]. But, there were times when I went into a shell, and my wife saw me through this. Caregiving can be very intense. I think it was only when my he passed away that it hit me like a tonne of bricks. I realised that grief never leaves, it sits with you... It changes you.”

PR professional Mansi Shah feels that recognising prolonged grief as a disorder will go a long way in validating experiences like hers. Shah lost her 43-day-old son in 2015. “For almost a year, I locked myself in the room. I stopped talking to people. My husband insisted that I visit a therapist, but I refused.” Shah’s son choked on milk. “Though I had a short time [with him], I still made so many memories with him. A part of me, still wants him to be there. It’s sad that what we go through gets reduced to labels like depression or PTSD. But the truth is that this is plain grief,” says Shah, who has become over-protective about her daughter, born in 2017. “I am constantly anxious about her.” “People say that time heals. How do you explain to them that I grieving every day?”

In her 25-plus years of research, Prigerson has heard from mourners “who are stuck”. “They describe feeling as if in the movie Groundhog Day reliving the recurrent nightmare of their loss—as if in a never-ending state of misery —persistently agitated and upset, unhappy and forlorn, triggered by reminders of their loss that derail their day and ability to focus. They anticipate no hope of a more contented future,” she says. It’s also why PGD as a disorder is most strongly associated with a mourner’s suicidal ideation.

PGD, according to research, has also been found to significantly increase a mourner’s risk of hospitalisation for heart attacks, and heightened risk of high

blood pressure and cancer, making it a medically-relevant condition, she says.

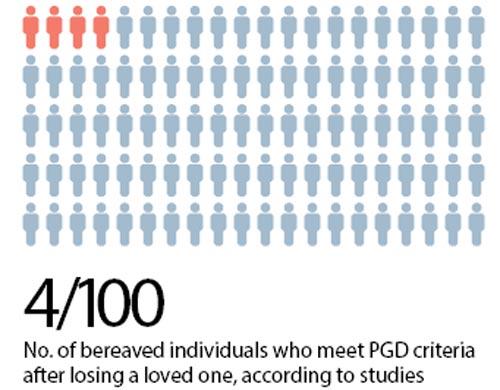

Prigerson, however, cautions against mistakenly jumping “to the conclusion that anyone who was missing a decedent and grieving after a year would be diagnosed with PGD”. “Studies find that roughly four of 100 bereaved individuals will meet PGD criteria a year after the death,” she says.

Prigerson and team have introduced PG-13-revised (PG-13-R), a self-diagnosis scale that contains 13 items that can be used for the dual “purposes of assessing grief intensity continuously on a dimensional scale and diagnosing PGD” (see box).

Dr Kersi Chavda, consultant psychiatrist, PD Hinduja Hospital and Medical Research Centre and Sir HN Reliance Foundation Hospital, says that grief can be considered an abnormal reaction, especially when it incapacitates you, and comes in the way of your normal “social and occupational” way of life. “Yes, there is this argument about medicalising grief [otherwise a normal event], but perhaps with this new development, doctors may look at those experiencing grief, slightly more stringently,” he says. “It does now sound that a person who grieves, and grieves will need medication.” He, however, feels that in India at least, it’s going to take a lot of time before PG is even accepted as a disorder. “Grief would not normally be seen as something that someone would seek help for. But, the situation that exists today, is much better than what it was eight years ago. And people are willing to seek help. In that way, I am fairly optimistic.”

Psychotherapist and counselling psychologist Malvika Fernandes agrees with the term prolonged grief, but has trouble accepting it as a “disorder”. “The good thing about having PG in the DSM is that now it will at least get the importance and relevance that it deserves. The flip side is that we then look at it from a very clinical lens. Biopsychosocial factors play an important role in how we grieve. Also, the more the socio-cultural support, the better is the prognosis of grief—if you are in an environment that allows you to grieve and converse about your loss, I think the prolonging of the grief will reduce. We cannot rush grief. By labelling it as a disorder, giving it a timeline, which indicates that you might need medication, it comes in the way of grieving. Grieving may take six months, six years or six decades—it’s about how you feel about the person gone, the loss and the memories, and values you have lost in the process, and making meaning of your life, while accommodating that loss in your life. It cannot be so black and white.”

Addressing misconceptions about PGD

By Holly G Prigerson

Why not focus on treating depression? Because these treatments have not worked for PGD. The people who contact me say that they’ve tried everything, including anti-depressants, and nothing has proven effective. They’re willing to try anything that might offer hope of being released from the stranglehold that grief has had on their lives. Many say that while they may not want to kill themselves, they also don’t see much point in living. Some wish to be reunited with the deceased loved one in death. Others appear desperate for help.

It medicalises a normal life event. PGD has been found to significantly increase a mourner’s risk of hospitalisation for heart attacks, and heightened risk of high blood pressure and cancer, making it a medically relevant condition.

PGD stigmatises mourners. We asked bereaved people about their feelings of stigma and 90 per cent of those who met criteria for a diagnosis of PGD reported that they would be relieved to know that such a diagnosis was indicative of a recognisable psychiatric condition; 100 per cent reported that they would be interested in receiving treatment for it.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!