Anand Patwardhan’s latest film crashes into the personal lives of his nationalist parents to build a world of the unsung who dreamed of a free India

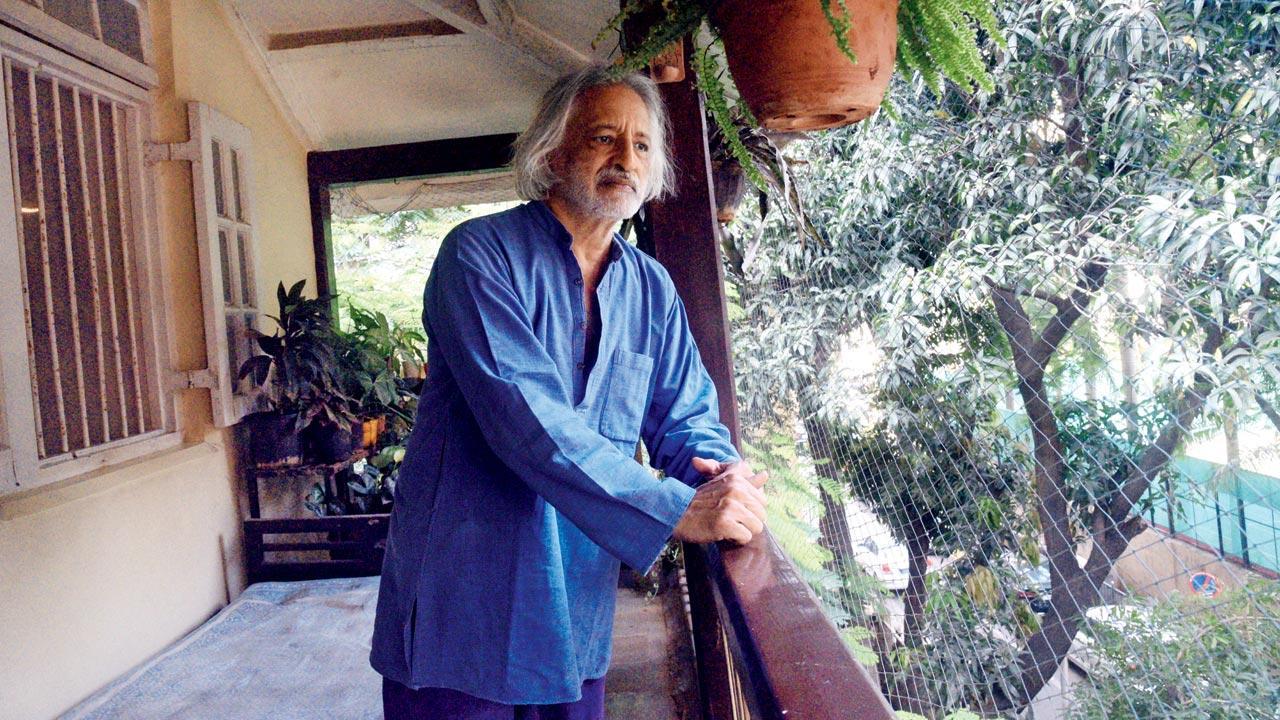

In the pandemic, filmmaker Anand Patwardhan began editing the footage he had taken of his parents and stitching it against the larger background of the freedom struggle, into what has become his 18th film. Pic/Pradeep Dhivar

The World is Family is filmmaker Anand Patwardhan’s first personal movie—snippets of videos he took of his parents Wasudev ‘Balu’ Patwardhan and ceramist Nirmala ‘Ni/Nima’ Patwardhan. Through it, he connects the personal to the political: His granduncles—Rau and Achyut Patwardhan—were among the countless nationalists fighting for India’s freedom; a dream that is now distorted into a communal dystopia. But the soft core of the 90-minute documentary that will be showcased at JIO MAMI Mumbai Film Festival this evening is the family that is Patwardhan’s world—the affectionate bond between his parents. And the star within—at least for us—his caustic, no-nonsense mother who smokes continuously through the film. And when she’s in the hospital for a tumour, she says, “I have no complaints; I brought this upon myself.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The couple met when Balu was in Karachi; Nirmala Dialdas, a Sindhi, and 12 years his junior, knew she loved him, while he just saw her as a child. The larger values of the freedom fighters are clearly distilled into the family. “Non-interference,” says Anand, putting a finger on it. “There must have been tensions between them as my mother was gone a lot [as she went to work with ceramists around the world], but my father supported her.” Their shots together are vignettes of their friendship” “Okay, I’ll use your brain; it’s better brain,” he says with a chuckle when she instructs him to “not use his brain” and just put the sweater on. “No one is going to come in to see your old man things,” Nirmala admonishes him when he locks the door to the toilet, which he is not supposed to.

His mother, whom he repeatedly teases, saying “funny mummy” (“Yes, I am a funny mummy,” she responds) was permissive, allowing him to skip school when he wanted, home-schooling him much of the time until he was sent to boarding school because there was no one to look after him as she travelled. “I... had never heard… stuff like… grown-up men don’t cry,” Anand’s voice-over says, reciting a poem he had written, “where with tears in both our eyes we parted/big sissy and small, forever friends.” “My father never raised his voice, never scolded me,” says Anand.

Against this mindful, gentle upbringing, it’s easy to see Anand’s disappointment in the “derailing of the India that our freedom fighters had fought for.” “The ideological mentors of those in power today did not fight for India’s freedom or go to jail, barring VD Savarkar who after being imprisoned in the Andamans, five times abjectly begged the British for mercy. He promised never to speak against the British if released and kept his promise. Instead he targeted Muslims and Mahatma Gandhi. Nathuram Godse pulled the trigger but as the Kapoor Commission found, there was evidence that Sarvarkar had masterminded the Gandhi murder plot.”

Nirmala Dialdas, Anand Patwardhan’s mother, with Gandhiji at Shantiniketan. Pics Courtesy/Anand Patwardhan Archives

Nirmala Dialdas, Anand Patwardhan’s mother, with Gandhiji at Shantiniketan. Pics Courtesy/Anand Patwardhan Archives

Interspersed with footage of his visit to his mother’s childhood home in Hyderabad, Sindh, his conversation with children in a school in Ahmednagar that Rau helped set up, and footage that his mother recorded of Achyut in Chennai, are conversations with other freedom fighters. It’s their candidness and a sense of fun and excitement to be part of the movement that makes this watch refreshing and endearing.

“For all his talk of democracy, Nehru was a snob,” says Anita Ghulam Ali, a one-time minister of education in Sindh, who also bemoans that they have been served non-alcoholic drinks, “When my father put his arm around him, he shrugged it off.” In another shot, she says, “He was so handsome when he was young; as he got older, he started to look like a monkey.”

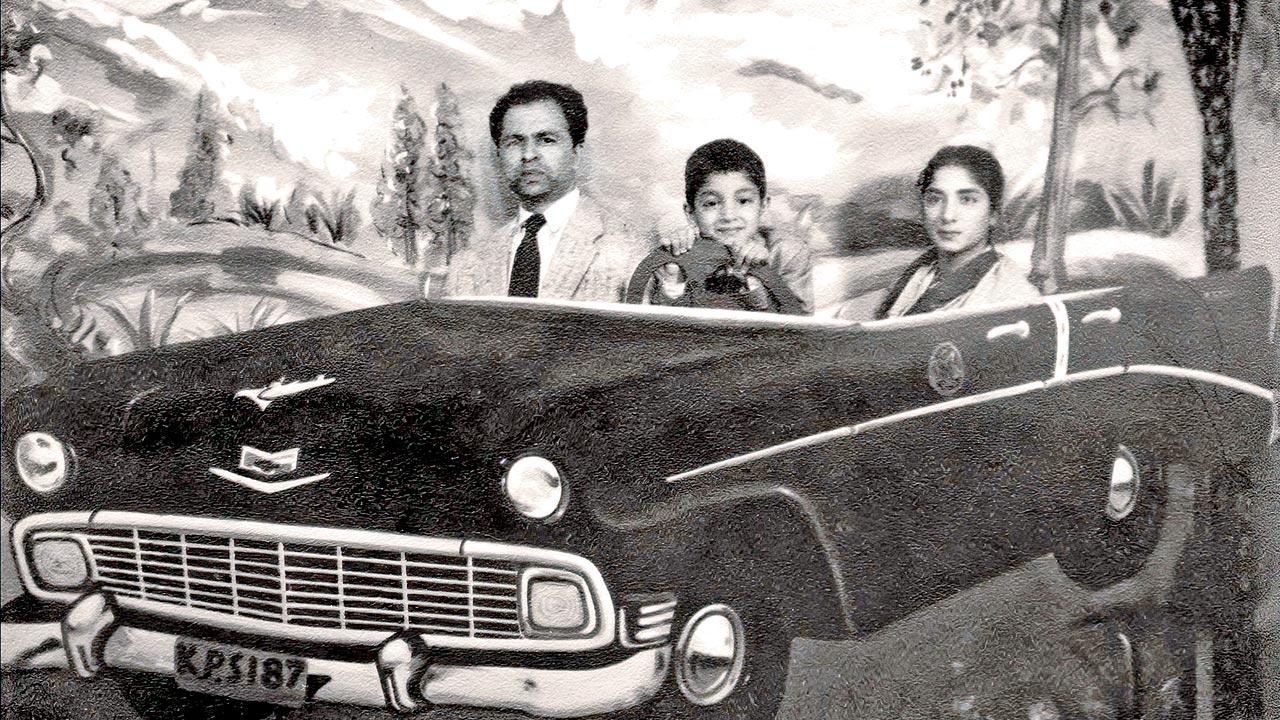

The Patwardhan family—Wasudev, Nirmala and Anand

The Patwardhan family—Wasudev, Nirmala and Anand

Ira Chaudhuri, his mother’s friend and contemporary says, “Some days my bosom used to look so big because I was hiding pamphlets in it [for marches]. My mother was famous for not throwing anything away. Years later, we’d try to put on a shoe, and couldn’t, and would find a pamphlet balled up inside. We were so different from our Parsi relatives, who aligned with the British. We were so mean that we used to tell them, ‘You’ll all be hanged after Independence.’”

Parallelly, he brings out other nuanced facts of the era that shaped the shade of independence the two countries finally got—that the British did not allow working class Muslims to vote on the matter of Partition, only the Muslim elite that was afraid that a socialist Congress would take away their property.

Anand’s granduncle Achyut Patwardhan (third from left) was a nationalist

Anand’s granduncle Achyut Patwardhan (third from left) was a nationalist

“You can see this in the cinema of the time, all the way to the 1980s,” he says, “The films made by Mehboob, KA Abbas, V Shantaram, Raj Kapoor, the music of Sahir Ludhianvi, Shailendra and so many others inspired by the secular-socialist orientation of the freedom movement. It’s so different from the kind of rubbish being made under the banner of patriotism right now and being peddled as the truth to stir communal animosity. There may be a kernel of truth—three Hindu girls became jihadis in Kerala—not 300.”

We are speaking to Patwardhan in his Dadar home, packed with ceramics made by his mother and her contemporaries—an art form he didn’t take to, though his first camera was his maternal grandfather Bhai Pratap Dialdas. It’s densely populated with posters of his films, a modern print of Gandhi ji, with whom his mother had a personal connection, plants, portraits of his family, cushion covers in Ajrakh. There’s a terracotta miniature of a traditional Sindhi jhula behind him, under a freehand portrait of his mother.

What if instead of the sanskari, bindi-sporting self-sacrificing Mother India we try to manufacture, this is the motherland we need? A rational, sensible one who respects everyone’s individuality and makes place for everyone.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!