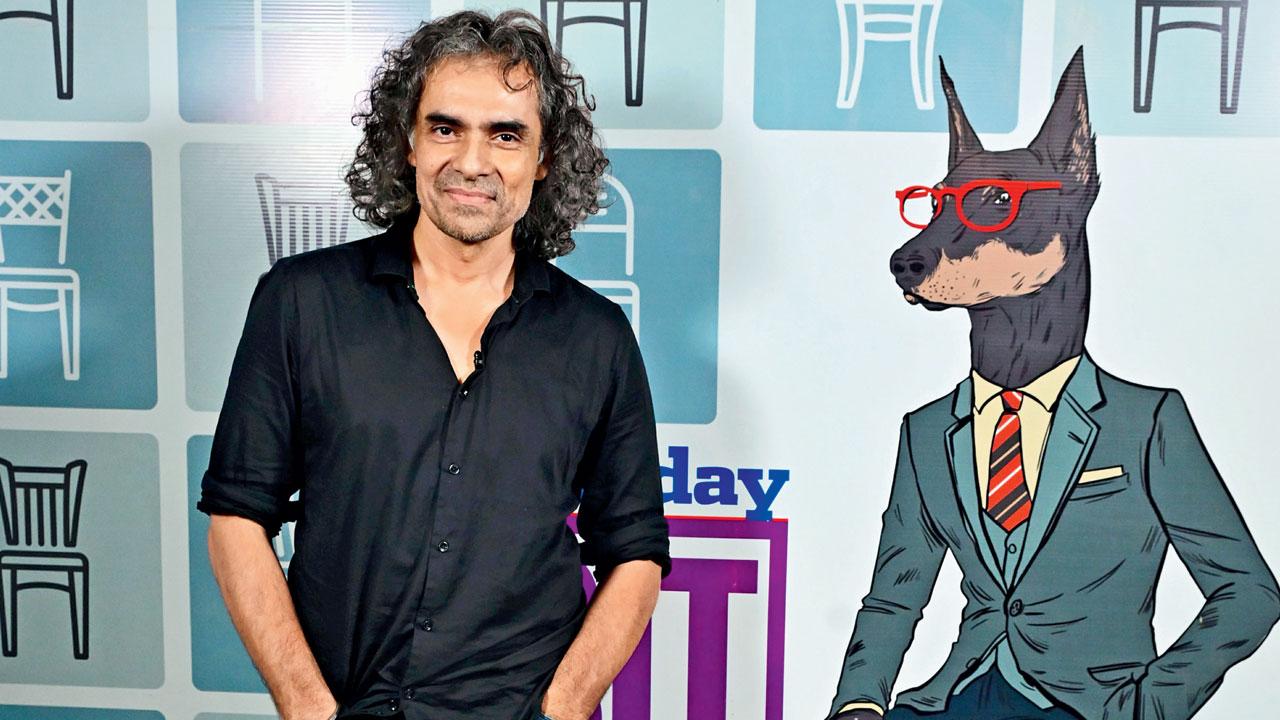

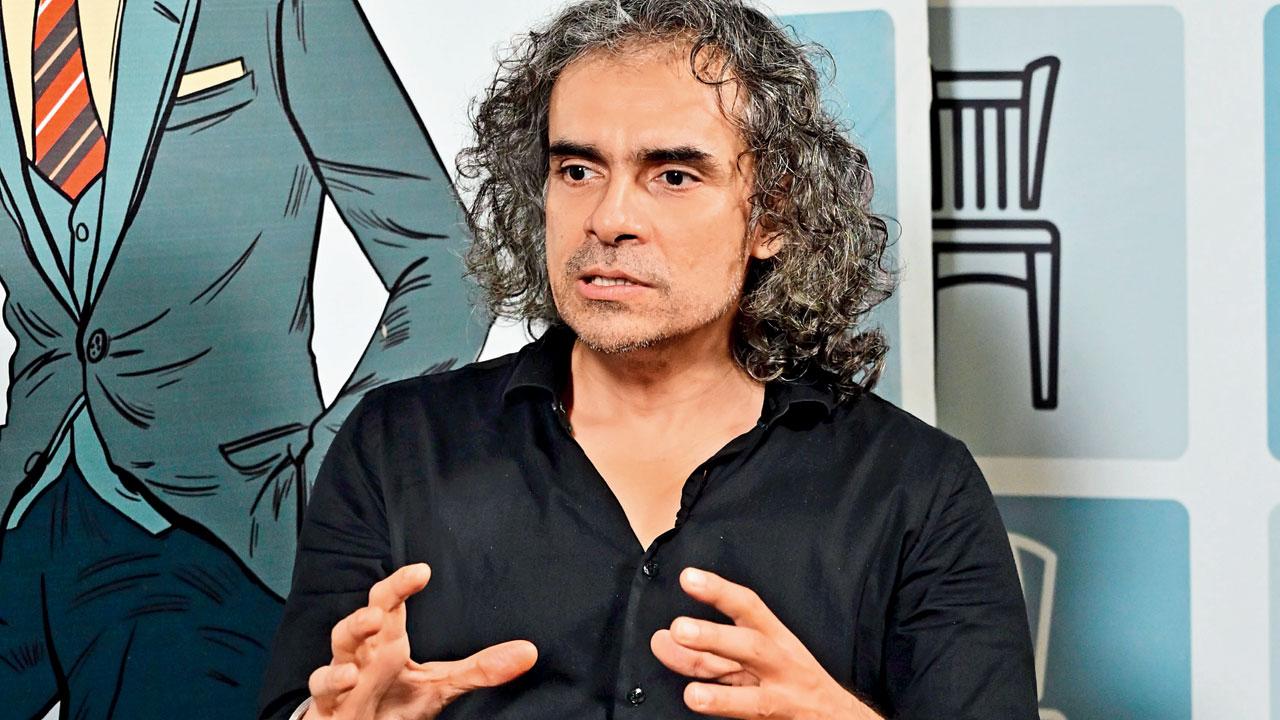

On Mid-day's Sit With Hitlist, Imtiaz Ali goes back in time to share anecdotes from his first film Socha Na Tha, right up to the latest, Amar Singh Chamkila

Filmmaker Imtiaz Ali with mid-day’s entertainment editor Mayank Shekhar at the latest edition of Sit with Hitlist. Pics/Shadab Khan

Whatever you do, sir, just don’t fix the money [for your next film], before calling me,” actor Shahid Kapoor told director Imtiaz Ali, in 2007, when Jab We Met (JWM) had opened “lukewarm” in theatres.

ADVERTISEMENT

It’s going to become a big film, Shahid suggested to Imtiaz, whispering to him then, “You could charge 2X of what you’re thinking [in lakhs], or you know what? It could even be a crore!”

Imtiaz was set to do Love Aaj Kal (2009). Negotiations were on. He waited it out, upon Shahid’s advice. He says, “It was Dinoo [producer Dinesh Vijan], who suffered!

“You ask him, he will never forget this. He is like, ‘Sir aapne jo number bola, [the number you quoted], my head hit the roof’. I said, blame Shahid!”

Anushka Sharma and Shah Rukh Khan in Jab Harry Met Sejal (2017)

Anushka Sharma and Shah Rukh Khan in Jab Harry Met Sejal (2017)

Shahid had recalled to us (on Sit with Hitlist), telling Imtiaz, not to carry a script with the name Geet (working title for JWM), given the heroine’s name on it, when shopping around for the hero!

But it’s actually Shahid, Imtiaz remembers now, who reminded him about the Jab We Met script, in the first place. He’d heard about it from others, while it was being passed around film industry folk.

Shahid had dates available. As did co-star Kareena Kapoor, who was going through the more important size-zero regimen for Tashan (2008), the supposed blockbuster in the making (that she explains in detail, in another episode of Sit with Hitlist).

Both said yes, and Imtiaz had literally a “window of 21 days” to get on shoot, while the screenplay wasn’t absolutely complete, dialogues had yet to be written, let alone pre-production, for locations to be locked, etc.

The script that Imtiaz had gone over to Shahid with is the same one that he met Ranbir Kapoor for, years later. That movie is still to be made—about time, we say! Ranbir took the said script with him to read, but asked Imtiaz about Rockstar (2011), instead.

It’s the story that, once upon a time—right after Imtiaz’s debut, Socha Na Tha (2005)—was to be made with UTV, starring John Abraham in the lead! Nothing came of that Rockstar.

Ranbir Kapoor and Deepika Padukone in Corsica for the film, Tamasha (2015)

Ranbir, in fact, narrated Imtiaz’s Rockstar story to Imtiaz himself. He’d heard it at a friend’s place, a few days from when they met: “Sir, let’s make that film,” he proposed.

Hearing Ranbir narrate the script, he knew that’s the actor to cast. This is post Ranbir’s debut, i.e. Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Saawariya (2007), which Imtiaz hadn’t watched still. The reverse-narration was the clincher.

Now, there are wholly savable Word/Finaldraft documents, and the computer, of course. “Despite everything”, Imtiaz admits, he had lost that script.

He rewrote Rockstar, from memory, for Ranbir. “The common thing between Ranbir and [and his wife now] Alia Bhatt is that I met both at a screening,” Imtiaz recalls.

Alia did Highway (2014) with him. She was not the original choice. He had a maturer actor in mind for the role, someone perhaps in her 30s: “Aishwarya Rai, without the make-up, maybe. It was that kinda film.”

While his core crew wasn’t convinced about Alia in Highway, he got her over to the office, to narrate the film to everyone. Done with that, the unit was satisfied.

It’s a hack he’d learnt from Ranbir’s narration of Rockstar. He tried it on Alia. Two unrelated people, “who have a kid together now; how filmy,” Imtiaz laughs.

We remember Alia telling us (on Sit with Hitlist) about how she seduced Imtiaz into casting her in his film (any film)—when she set her eyes on the director, at the screening of Luv Shuv Tey Chicken Khurana (2012).

Which is not how Imtiaz remembers it: “She’s just sweet!”

He handed her a novella-like outline of Highway; called her up later to check on what she felt. He could tell she was petrified. Given that she’s in every scene of the film.

He went over to meet, where dad Mahesh Bhatt was convincing her to go for it: “He’s a nice director.” Alia had said it was simply her dream to work with Imtiaz.

In fact, this profile, heavily excerpted, is almost wholly around anecdotes that other guests on Sit with Hitlist, this conversation series, have narrated, on Imtiaz himself.

The entirely unedited, fun chat, on video, is uploaded online. The other person, who inevitably shows up in most conversations to do with Bombay film talents, who were similarly newbies in the ’90s, is Mahesh Bhatt, aka semi-godman Bhatt Saab!

Imtiaz says, “Bhatt Saab was the first person to offer me to direct a film. He was planning on retiring as a director. He had seen an episode of Imtihaan, a series I was doing for Star Plus. Manoj Bajpayee was in it. He called me up one day, and asked me to meet at his office.”

Imtiaz went over to Bhatt Saab’s workplace—far too packed with people, over a majlis, listening to warm sermons on life, films, the works. Imtiaz was intimated.

From across the floor, Bhatt Saab shouted out to Imtiaz, “I’ve seen the scenes you’ve shot; loved this, didn’t like that, blah blah, blah… You’re directing my next film. Now go, I don’t have time.”

Totally taken aback by what had happened, Imtiaz called Bhatt Saab back, from the pay-phone, downstairs, “‘Sir, I didn’t understand what you said.’ He laughed, and asked me to come back the next morning. That was a movie to do with two musicians. Bhatt Saab was going to write and produce it for Vishesh Films. I hope to make it someday.”

Imtiaz, as is widely known, was born and raised in Jamshedpur, then Bihar, now Jharkhand. You can see his Jamshedpur in Vikramditya Motwane’s Udaan (2010), which is not a happenstance.

As Vikramaditya had told us, he had got Imtiaz to read the script, who asked him to stay over with his family back in his hometown, to get a sense of the setting. It made sense for Udaan to be placed specifically in the steel township of Jamshedpur.

Rockstar (2011) and Jab We Met (2007) remain among the most iconic films of Ranbir Kapoor and Kareena Kapoor Khan’s careers

Imtiaz’s younger brother Sajid, a school kid then, used to show Vikramaditya around—who, in turn, felt Sajid would make for the perfect lead actor for Udaan.

The film remained stuck between producers, over years. By which time Sajid had grown up. He debuted as director with the romantic musical, Laila Majnu that, as we speak, six years later, has made a rerelease/comeback into theatres, vastly outpacing collections/footfalls, from when it first opened in 2018.

Vikramaditya and actor Abhay Deol were childhood buddies. Which is how Imtiaz and Vikramaditya met. Abhay, the young Deol in town, was looking to enter films, ideally with fresher ideas/talents.

Imtiaz, who had been working in television—after graduating in advertising, from Mumbai’s Xavier Institute of Communications—went over to Abhay’s place to narrate his script.

Abhay needed a close bouncing-board for a second-opinion. He called his friend Vikramaditya over. Likewise, Imtiaz says, he took his friend Anurag Kashyap along for the meeting.

Such is how Socha Na Tha (2005), both Imtiaz and Abhay’s debut film was born. Whether or not right there, and then, but certainly seeded in the same room.

Imtiaz’s career since has largely been marked by strong romantic films, but all the more associated with Punjab. For the Bombay film industry itself, Punjab, as the prime muse, is hardly a surprise.

Most top Bollywood stars and producers have had their ancestral roots in the land of five rivers. The nostalgia around which—sarson khet, bhangra, giddha, karva chauth—have inevitably showed up in their popular works.

Imtiaz, though, is from Bihar—having also spent seven years of growing up in Patna, where his father was posted. Not that he has an iota of a Bihari accent. Which, he says, is more because of Jamshedpur, which is an altogether cosmopolitan town.

He’s sure to switch into a Bihari twang, while responding to it. In the same way, he says, among Delhi-ites, can go full ‘Delhi’. That’s where he went, to Hindu College, to read English literature. He can similarly react to the Punjab accent.

How come Punjab, though? He wears a kada alright, that was gifted to him, when still in school, and he’d visited Punjab on a holiday then. But, that’s it.

“Punjab began with JWM,” he says. And has, of course, continued with his last film, Amar Singh Chamkila, the most deeply felt, insider’s account of the state, where both compassion and blood flow (always has).

Chamkila is also the most watched Indian film on Netflix.

Imtiaz had first set JWM in Rajasthan. But his feisty, female lead character, Geet, and her words, fitted in more with “Sikhani girls, who I had interacted with a lot in Delhi.”

The train of JWM, hence, moved to Punjab instead. Namely a small-town called Nabha. The locals thereafter guided him towards achieving authenticity. He’s since been drawn to “the land of grace, mysticism and love.

All the great lovers in India have been from Punjab.”

Which isn’t to say he hasn’t subverted the setting enough, or gone with clichés of old-world Bollywood altogether. My favourite instance is him placing a Brazilian model, Giselli Monteiro, as a ‘kudi’ from the ancient Punjab pind, in Love Aaj Kal (2009)!

Imtiaz was looking to cast Giselli—visiting India on an assignment—as Saif Ali Khan’s Latin American girlfriend, in the London/modern portions of the pic. Looking at her, his co-producer, Preety Ali, suggested her for “Harleen Kaur [from Brazil] for Punjab!”

He had similarly picked Nargis Fakhri—half Czech, half Pakistani, fully American, from Jackson Heights, Queens, New York City, as a pucca Delhi-ite, from Kashmir, in Rockstar.

He spotted her in an ad, in a fashion magazine. Whether or not that casting convincingly worked out, Imtiaz reasons the idea behind it was to find a “dil todne ki machine [complete heartbreaker]—someone so out of the league, in terms of looks, face, body, even for Ranbir!”

In hindsight, he does feel he could’ve factored in the bit that she was American, into the script. Nargis’s casting was strongly criticised, if you recall, after the release of Rockstar.

Imtiaz defends himself with the same film’s successful rerun in theatres recently: “Nobody expressed a problem with it now.” Nargis’s character Heer is from St Stephen’s, which is the college across the road from Hindu, where Imtiaz went.

I reckon if it’s his most personal film, yet? Imtiaz agrees. More so, for its central question—about whether success, in general, let alone the arts, was possible, without experiencing sufficient turmoil in life.

It’s something Imtiaz had grappled with himself. He says, “During interviews for Chamkila, I realised, even Diljit [Dosanjh, his lead actor] had grappled with the same dilemma: ‘Koi tragedy nahin hai [No tragedy], how will I become a singer?’ And then he says, so nicely, ‘Koi baat nahin, continue karte hain [Never mind, let’s continue]!’”

The other theme that Imtiaz related to most deeply was “illogical attachment” with issues that, otherwise, we have no engagement with, but have empathy for—the fact of ‘Sadda Haq’!

“Even in my own movies, there are moments that move me, but I don’t know where they come from, in terms of a [direct] source. That said, the character, Jordan, is nothing like me. The thoughts are.”

At Hindu College, Imtiaz named and founded Ibtida, its dramatics society, that runs even today. During his time in Delhi, he belonged to what he calls the “Mandi House jhol”.

Meaning, the theatre scene in and around the National School of Drama (NSD), with independent groups, such as Act One, headed by NK Singh, that he was part of—along with the likes of Manoj Bajpayee, Piyush Mishra, Shoojit Sircar, Ashish Vidyarthi, Gajraj Rao, Prashant Narayanan, and the lot.

These are well-known names, and the list grows big enough to avoid recounting—for the number of creative talents, who moved to Bombay, around the same time, from Delhi, to work in the film industry.

Establishing a new filmic voice of sorts—Vishal Bhardwaj, also from Hindu; Tigmanshu Dhulia, from NSD; Kashyap, from Hansraj College; Saurabh Shukla, from next-door Khalsa (the latter two wrote Satya, 1988)…

Imtiaz, 53, says, “Somebody must do a study [on how that came to be]. We were all friends, or friends of friends; often crashing at each other’s homes. This was the generation that was both ‘Sholay’ and ‘Shyam Benegal’.”

Delhi’s Act One had a “sister-concern, with similar values”, Barry John’s Theatre Action Group (TAG), that shared talents, on occasion.

That’s from where emerged Shah Rukh Khan, who had dropped out of the mass communications programme at Jamia, after a successful stint on television in Delhi—establishing himself, soon enough, as the ‘King of Romance’ in Bollywood.

Imtiaz, as a director, broke out with the romantic genre as well. Surely, he would’ve thought of Shah Rukh for his star at some point?

“No, he was too big; never on the anvil. For that matter, even now, I can’t think of Amitabh Bachchan. He’s too big for me. Even Mr Bachchan doesn’t realise how big he is. I have seen people pull out theatre seats, because he’s appeared on the trailer for Geraftaar [1985]!”

Shah Rukh and Imtiaz did team up on a romance together—that’s Jab Harry Met Sejal (JHMS, 2017). It’s a film that, Imtiaz says, pretty much got triggered from a Facebook comment on Tamasha (2015).

Possibly his most polarizing picture—loved to death by many. While some got bored to death as well, questioning the realist basis of the male lead (Ranbir). Which is, to be honest, really their bad. If they didn’t get it, that is.

“Well, there is something snooty about the appreciation for Tamasha. It’s become the club that I never saw myself in. I used to think, I’m a sell-out. So, I just wanted to make an easy, accessible film [with JHMS],” Imtiaz says.

It was the biggest ticket film—genre, star, and director, perfectly in sync. But I don’t think he sees it that way. Again, in hindsight, criticisms or box-office apart, you wonder what he thinks he could’ve done differently with JHMS?

He says, “With theatre, television, and films, I’ve worked the same way. Written a story, and brought it together, through actors. Which is what I did with JHMS.

“The fact that Shah Rukh is a humongous star is something I hadn’t made a provision for. Because, in life, he’s such an easy and accessible person—he doesn’t give you that impression, either.

“Of course, there are enough good things in the film, which get lost [when it’s not accepted]. But I could have brought in a flashback, a backstory, and Shah Rukh, as the star, could’ve been used to the best of his strengths.”

Going back to the Delhi crowd that made the ‘new Bollywood’ in the ’90s, as it were—where Imtiaz seems separate from the mainstream-indie, migrant directors, that emerged then, is foremost with music.

He remains among the few realistic, new-age filmmakers, indulging deeply with romance, song picturisations, lip-syncing, adapting soundtrack, as situations, into his scripts. That is, after all, an inherited art-form, syntax, and grammar—threatening to die with later talents.

All of it, he says, comes from growing up in Jamshedpur. If you’ve seen Cinema Paradiso (1988), that’s him—young boy sitting behind the projectionist, switching reels. His family owned Jamshedpur Talkies and Karim Talkies, two local theatres, that he had complete access to.

He says, “I’m inherently drawn to the ‘cinema-ness’ of cinema. The moving melodrama, that actually comes with music—to represent mood, feelings, turns [in the story], or time transition, through montage….

“And I found myself so lucky to be in the company of such crazy and kind musicians [Sandesh Shandilya, AR Rahman], who literally opened their doors for me [to work with them]. I find music composition to be the highest art form.”

In that respect, his strongest collaborator, in terms of writing, might well be the “shayar” Irshad Kamil, from Malerkotla (Punjab), whose lyric is essentially an extension of dialogues, in Imtiaz’s films—they’ve worked on each one together.

Imtiaz found Irshad, through Sandesh. They instantly bonded over the common love for poetry: “In this city [of Bombay], you crave that, and when you find a person like that, you catch that person!”

Speaking of getting caught, the most hilarious anecdote I’d heard about Imtiaz and Irshad was actually about how they were once caught by the police together.

This is on Versova beach, past midnight. Him, Sandesh and Irshad, lost to the world, discussing music (for Socha Na Tha).

“Those days, if we had to meet at night, it had to be outside. Homes were small. People would be sleeping inside.” In comes a cop, wondering what these guys were up to on the desolate beach.

“It was 2 am, but it’s not like we were up to anything nefarious… Irshad said we were making music.” Which is probably the lamest explanation/excuse the beat-cop would’ve heard in his life, over three men, allegedly gallivanting.

Next thing they know, they’ve been put inside a police van. Further, into the police station. They were right in the middle of having arrived at a track, though.

Each time they regrouped, whether in the van, or the police station, they simply carried on with cracking the idea: “Well, we knew, if we get the song right, none of this will matter!”

There is a charming stoicism about Imtiaz. You can sense it in his company. He’s also an engaged conversationalist, never repeating stuff you’ve heard him say before. Totally in the moment; mulling, responding, detaching, yet fully interested.

It’s probably the same way he handles personal fame. I know this from independent sources. As in, friends, who’ve bumped into him at local bars/restaurants in the past. Imtiaz being among the few directors, who’s so public a face.

As he puts it, in another context, quoting Buddha, “Eyes half open, half closed. Half with yourself, half with the world. It’s such day-dreamers, who drift into the film industry. Instead of the other way around. It’s a boon to make a living out of dreaming.”

Even while he was looking to make films, and surely, it’s a struggle for everyone, he says, he was fine, the way he was. “You never really make it, anyway. Manisha Koirala told me once that when she was in Bombay, auditioning for films, that was her life.

“If nothing ever happened, she was still satisfied. Only if she felt dissatisfied [for any other reason], she would have returned, done something else.”

That said, certainly the rigours of film as an industry can get to most—hits, flops, etc. Consider the unusually cold streak that Imtiaz had, JHMS onwards—in particular, Love Aaj Kal (2020), or even stuff helmed as producer, Thai Massage (2022), series such as She (2020), Dr Arora (2022).

Whatever one’s personal opinions on those works, and those are subjective, anyway—they didn’t turn out to be pop-culture moments, or at least haven’t, yet.

And that Chamkila (2024) was, effectively, the comeback, as it were? Does he ever feel that he’s on a rough patch? He says, “Always! Because you’re always engaged, with a certain [new/next] challenge. I’m only worried about that, at any point in time.”

Going by the theme of picking moments from Sit with Hitlist, when guests have brought him up, there is a not-so-positive one, if you may.

“Bring it on, I love negative stuff,” Imtiaz smiles. That’s when his lead actor Sara Ali Khan mentioned to us that she hated herself, in the new Love Aaj Kal! Or, at least, something to the effect.

On the film itself, he says, “You know, my English teacher, Swaroopa Mukherjee told me, when she saw Love Aaj Kal, that it remined her of her English classes.

“She said, ‘There is this strange thing that when you explain things to young people, and ask—have you understood? They say, ‘Yes miss, I’ve understood. But, actually, they haven’t.

They never say—no, I haven’t understood. There was something very sensitive in there, and the youngsters in the film, perhaps, didn’t get what you were trying to say’.”

He adds, “I’m not blaming Sara. The point is that direction is a process of working with an actor. The actor, who has surrendered, is not obliged to understand. They have said the words/lines. I couldn’t get through to the actors, to own the material [in Love Aaj Kal].”

Going beyond stars, it’s my turn now to pose to Imtiaz something that has annoyed people, at large. And that’s do with fans of JWM!

When asked during a recent interview about what he thought might happen to the it-couple, Geet and Aditya, if the film had a sequel? He said, they would be at the divorce-lawyer’s office!

Only fair that I pass on the outrage. Imtiaz laughs, “That interview was before a live audience. I just thought it was a smart thing to say!”

Nope, not letting go that easy. “Well, films have to be dramatic. So—what if, they’re at a divorce-lawyer’s office? That’s the question. Now, if that’s the beginning of the film—the end will be happy, right? You start at a crisis, and come to a solution!” Well saved.

Final question, and this has to do with an old print interview of Imtiaz’s, that’s remained in my head since. Chiefly because there was no follow-up to his answer, and I kept wondering exactly what he meant, when he once said, “Married men are the most ch***** version of themselves!”

Mercifully, he remembers that decade-old interview. He smiles, “There was a context to it. Some of which I’ve forgotten now. All that remained was the headline!”

Go on? “Well, marriage in itself is nothing. Relationship and vibes are important. Anyway, I don’t believe in bracketing relationships. The problem is when people start playing ‘married’. The same thing applies to the wife.

“And then you dumb yourself down, playing ‘rules of the game’. Rather than respect each other, for who you are. That’s when you become a bad version of yourself.”

Okay, explain with an example? “That husband and wife are supposed to do things together. Why? Let’s say, I wanna go on a solo-trip to Jhumritalaiya, or read a book. And she wants to go to Switzerland, or watch a movie.

“You would, if you were friends; so why not? But you’re married people. So, what? And then resentment sets in. You start keeping secrets from the one person, you’ve actually sworn never to keep secrets from.”

Aptly, we’ve ended with precious gyan on love, from Imtiaz. Outside of films, of course. “Disclaimer: Please don’t follow anything I say. I know nothing,” he signs off.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!