I trod with trepidation filing a first half-pager on Aubrey Menen, whose Rama Retold was among the earliest books banned in the country. Followed by a detailed profile of Pranab Mukherjee on becoming Leader of the House in the Rajya Sabha after his finance minister tenure. “What’s to worry?

Mid-1980s at the Illustrated Weekly: (From left) Sailesh Kottary, Aravind Vidyadharan, Nikhil Lakshman, Sherna Gandhy, Maria Fernandes

Loss sharpens gratitude. The passing of Pritish Nandy takes me – and dozens of colleagues under his editorship of The Illustrated Weekly of India – back to the 1980s.

ADVERTISEMENT

Fresh from college, and hungry for journalism, we lucked out with this helmsman. Who brought politics and poetry to the post in good measure. Who called a spade a spade, no matter the consequences. Who believed enough in the youngest team members, sending them to confidently interact with the most famous and fearless. If he broke candid interviews with every reigning public figure, he as generously trusted us with those we held in gawping awe, typical of journos wet behind the ears.

I trod with trepidation filing a first half-pager on Aubrey Menen, whose Rama Retold was among the earliest books banned in the country. Followed by a detailed profile of Pranab Mukherjee on becoming Leader of the House in the Rajya Sabha after his finance minister tenure. “What’s to worry? Ace it. Just get your facts damn right,” Nandy said, emboldening rookie reporter me.

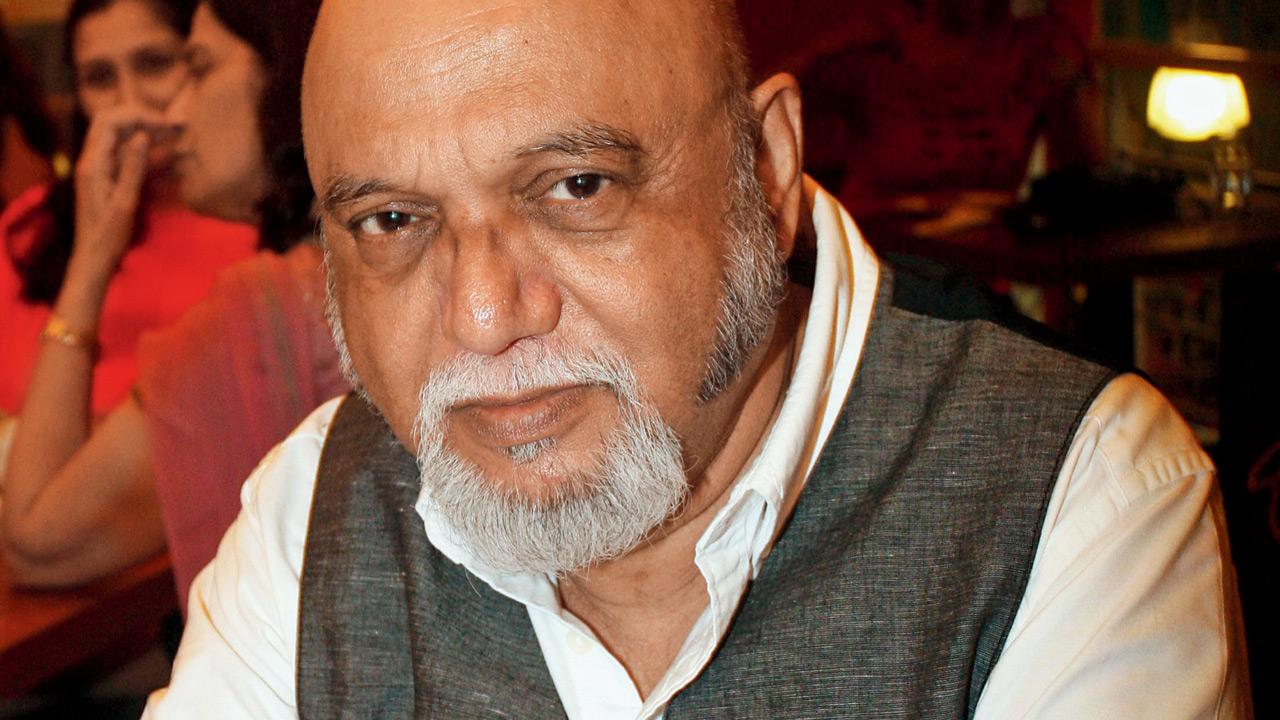

Pritish Nandy during a book launch in Mumbai in 2011. File pic

When Wole Soyinka won the 1986 Nobel Prize for Literature, I was assigned a salutary story. His editorial brief suggested I go with the idea the Swedish Academy cored in its statement: “In a wide cultural perspective with poetic overtones Soyinka fashions the drama of existence.” He loved my title to the piece. “The Maverick”. After all, wasn’t that quintessential Nandy too?

That was the time I handled the copy for Maneka Gandhi’s column called “Heads & Tails”. I enjoyed the fire and ire with which she championed animal rights. Yet, quaked to the tips of my Kolhapuris when she strode into the magazine’s fourth-floor office unannounced one morning, “to meet the person producing my page”. I needn’t have shivered. Standing beside my table in a crisp blue chikan kurta, she said, “Nice.”

Expectations ran high at the Weekly desk. Parallel with the insistence on rigour of thought and expression, Nandy (with deputies Sailesh Kottary, Sherna Gandhy and Nikhil Lakshman), dinned into us the vital importance of thinking visually. Nothing available online; even chunky box computers hadn’t made an appearance. We scurried to the reference library for pictures. Alongside, brilliant photo essays were commissioned by lensmen and women of the international ilk of Ram Rahman and Jaywant Ullal. A very young Dayanita Singh would quietly visit. Not to mention our ed’s several painter friends, led by Husain himself.

So, we surrendered writers’ darlings with ease. Till today, seldom will Illustrated Weekly proteges get huffy about cutting their own text in order to fit a fine photo or other artistic image. We wound text compatibly around the creativity of in-house illustrators and caricaturists. Equality over ego. Rare in subsequent editorial and art departments we worked with.

Thinking visually is a lasting lesson. Also essential to being a Weekly-ite was another quality exhortation: think laterally. Out of the box. Kaafi hatke. He’d say, “Think laterally” at the start of each gathering in his cabin to plot the next week’s pages. A fat 72 of them. Packed with inspiration. Replete with exposes of crooked chief ministers, fake godmen and similar holy cows. Conceived by a man in his brave prime then.

No doubt certain later exposes slanted towards personal ambition and controversial scoops. We’re able to separate the debate and questions surrounding some of his editorial policies, to appreciate much else. Mainly, how he had every writer’s back. The readiness with which he granted carte blanche to feature writers and investigative reporters helped critique innumerable establishment excesses.

Never did we dare submit sloppily dashed-off opinionated pieces. “What are you really saying here!” he’d storm. The rage was undeniably there. But as strong came the compliments on a job well done.

It was great learning all the way. Mere months before the death of AFS “Bobby” Talyarkhan in July 1990, I panicked. Nandy had slotted me to write a 10-page cover story on the legendary commentator at the Cricket Club of India over a series of Sunday afternoons. “I know little about sport, especially this game,” I pleaded. “Exactly why you should be doing it,” he responded.

Touche. Thank you, man of many surprises and mentor to more than you realised.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!