Celebrating a lady who has left us with much more than her wonderful translationof a book of quirky Parsi phraseology

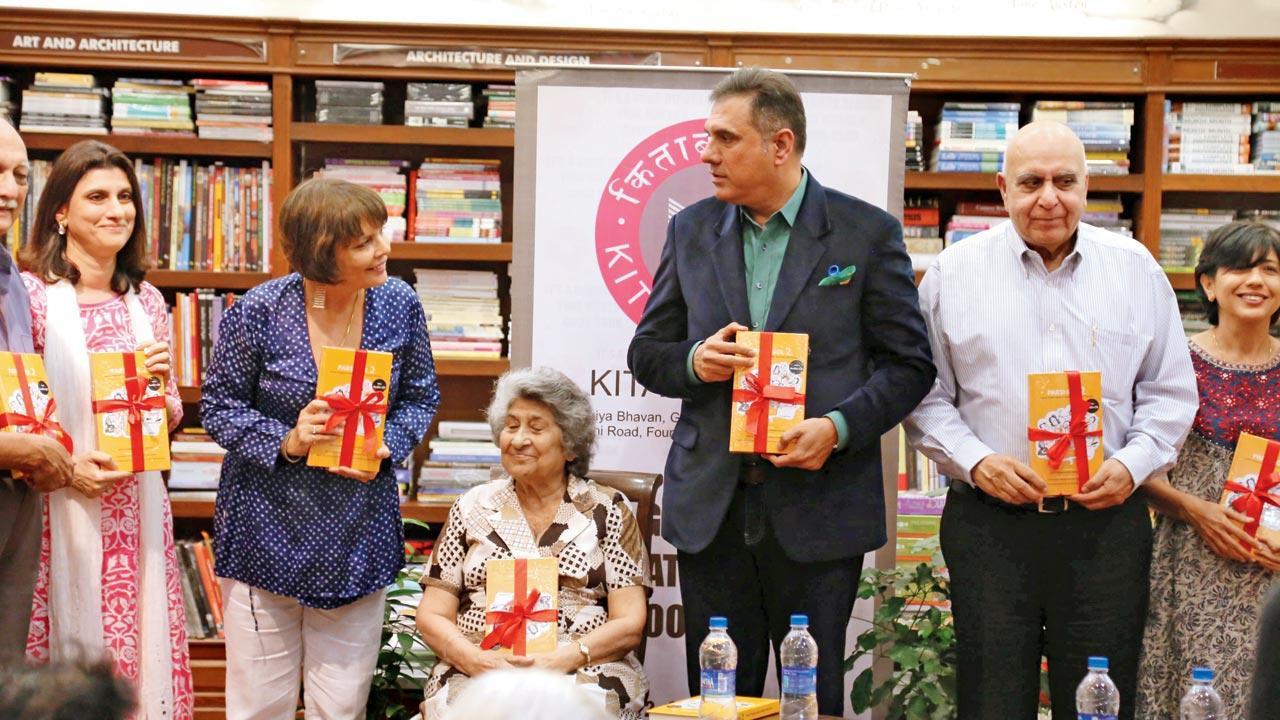

At the launch of Parsi Bol 2 in Kitab Khana: Meher Marfatia, Sooni Taraporevala, Rutty Manekshaw, Boman Irani, Dinshaw Tamboly and Farzana Cooper, the illustrator of the book. Pic/Firdaus Bativala

We lost her last month. And our lives are dimmed by a little less laughter and lustre for sure.

We lost her last month. And our lives are dimmed by a little less laughter and lustre for sure.

Rutty Manekshaw—Rutty Aunty to screenwriter-photographer Sooni Taraporevala and me—was the wonderful translator of two sellout editions of Parsi Bol: Insults, Endearments & other Parsi Gujarati Phrases, the book we co-compiled and co-published.

ADVERTISEMENT

She was Sooni’s father Rumi’s cousin. Over the years, Sooni taped Rutty, one of her favourite aunts, talking about the old times in Bombay—when she was a kid, family stories, popular entertainments of the city in the 1950s and ’60s… It was fascinatingly, resoundingly interesting.

Each time I wound my way up the high four floors of steep stairs leading to her flat in the 1890s-erected building called Station Terraces (skirting Grant Road railway station), it seemed no big trudge. “What will I hear Rutty Aunty relate today?” was the question my mind turned to easily. Keeping me happier climbing, looking forward eagerly to anecdotes and aphorisms alike.

On the front bench of her Italian class in Perugia, 1971. Pic Courtesy/Mehernosh Manekshaw

On the front bench of her Italian class in Perugia, 1971. Pic Courtesy/Mehernosh Manekshaw

Her hospitality stretched wide and welcoming. On reaching the dining table we sat around to work on, there awaited a regular feast of sandwiches and plump patties. Tasty treats from Belgaum Ghee Depot at nearby Nana Chowk. The trek down to ground level naturally proved more challenging on the full belly she decided we should leave her home with.

Encouraging my love for city history, she told me the tale behind the food shop’s quaint name. A patriarch of the Workingboxwalla family originally ran this as a business, selling ghee brought from Belgaum in 1943. Once snacks were introduced here, they became overnight hits. I had poor luck at the counter, never getting to it soon enough. The delicacies disappearing on demand, I stared disappointedly at empty shelves. But no fear on cheerful days of work on Parsi Bol; the Manekshaws had ordered the best in advance.

Having known her beloved Rutty Aunty all her life, Sooni says, “Right till the end when I met her, a few weeks before she passed [at just under 98], her memory was intact. What I will miss most about my Rutty Aunty was her prodigious memory and her capacity for fun. Rutty and her husband Minoo were part of a family gang that travelled, danced and partied together. Her recollections ended with ‘Aapre soo majha kidhi [What a great time we had]’.”

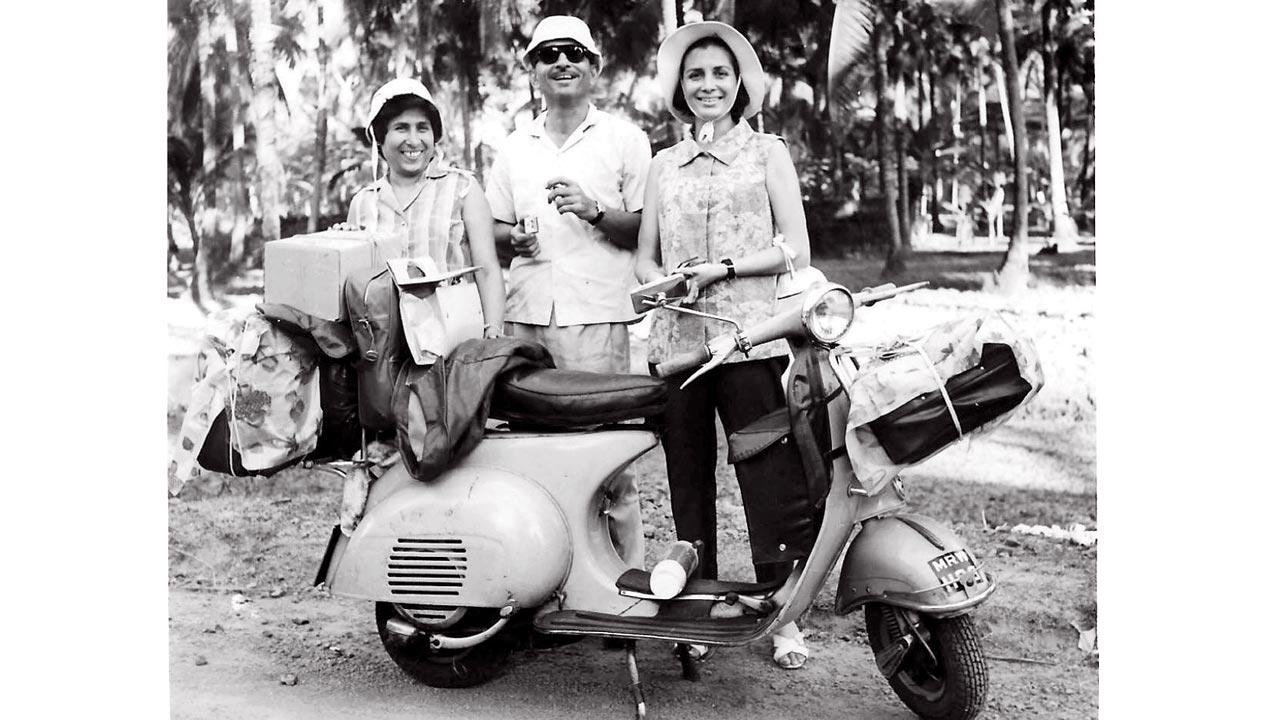

Manekshaw with husband Minoo and cousin Freny Taraporevala on their 1966 scooter trip through south India

Manekshaw with husband Minoo and cousin Freny Taraporevala on their 1966 scooter trip through south India

They frequently went out dancing in a city that then boasted the country’s largest number of live jazz bands, playing in cafes like Napoli, Volga, Berry’s, Gourdon, Gaylord, Talk of the Town and the Ambassador. “Ameh naachi naachi ne ardha thaya [We danced till we felt half our size],” she said, bemoaning that young people now are deprived of such affordable restaurant acts.

Avowed movie buffs, the Taraporevalas and Manekshaws often found themselves at Mayrose Restaurant, across from Metro in aptly christened Cinema Lane. “We parked outside Mayrose after Saturday night movies, with snacks brought to the cars,” recalls Rumi Taraporevala. “Having finished watching the film Rosemary’s Baby, in which Mia Farrow was impregnated by the devil, courtesy dastardly Dr Sapirstein, we jocularly hailed that evening’s affable waiter, ‘Sapirstein!’ He loved it, rushing to greet us saying ‘Sapirstein, Sapirstein’ whenever we pulled up for servings after that.”

Rutty Aunty added, “While making plans, we’d say, ‘Let’s go to Sapirstein’, not ‘Let’s go to Mayrose’.” Incidentally, Mayrose, hugging a corner of Kapadia Chambers, was formerly Ava Chambers, belonging to Gustad Khodadad Irani in 1938. If his wife’s name graced this awning, his father’s name was lent to Dadar TT’s Khodadad Circle.

With the Taraporevalas at her 90th birthday dinner party. Pics Courtesy/Rumi Taraporevala, Mehernosh Manekshaw

With the Taraporevalas at her 90th birthday dinner party. Pics Courtesy/Rumi Taraporevala, Mehernosh Manekshaw

Continuing to recall her fondest childhood memories involving Rutty Aunty, Sooni says, “Her son Mehernosh and I grew up on Lambrettas and Vespas. His parents had one, mine did too. In 1966, both couples embarked on a scooter trip around south India. Mehernosh and I were left to my grandparents and granduncle, who entertained us with trips to the circus and other such delights. The parents returned several shades darker to find I had not done any homework the entire time they were away.”

“Soona ghani masti kartee thi,” she told me, in a tone so indulgent, the roll of the eyes accompanying that remark amounted to nothing. Sooni was Soona for her. The daughter she never had. “Maari Soona” could do no wrong. Proud of her niece’s success as an internationally feted scriptwriter and photographer, Rutty Aunty would declare, “Our Harvard graduate is so humble and good at her Gujarati.”

Rutty Aunty had experienced an overseas learning stint of her own. Mehernosh shares a charming photo showing her as a keen front-bencher there. A pro at Gujarati, English and Italian, she worked for Montedison, the Italian chemicals company which sent her to Perugia in 1971 for a three-month immersive course in Italian. She was required to rank in the top two of her Italian class to qualify for that visit.

“No woman in our family had done anything close,” Sooni recalls. “When she returned, I hung on to her every story about that adventure, including how she dealt with bottom-pinching Italian men. It was only natural that we roped her in to be a collaborator on Parsi Bol. She not only matched our enthusiasm but exceeded it. Remembering a phrase, she’d write it in the middle of the night, to be relayed to us on the phone the next morning by Mehernosh.”

Her increasing deafness—hardly helped by the dhadam-dhadam-dham rumble of local trains reverberating loud over the old stone wall of Station Terraces—necessitated this slightly circuitous route. For that condition as well, she had the mots justes ready for comic relief, not self-deprecation. The last person to feel sorry for any impediment, she jokingly described her hearing loss, using the phrase “Behra ne behs” (literally “The deaf are in heaven”; idiomatically “Ignorance is bliss”).

Sooni points out, “Because she was equally adept at both languages, we were able to get translations that were nuanced, idiomatic and yet precise. She worked tirelessly, patiently and always with her characteristic sense of humour, not only translating but contributing many fine phrases herself.”

Mehernosh offers examples of a couple of pet phrases Rutty Aunty was given to using. There was “Aapru kidhelu aapri saathe (We create our own karmas)” and “Murva de (Let it go)” when she was fed up with something and wanted to put an end to the matter. A line she picked up from playwright Adi Marzban went: “Sagaa chhe te wala nathi, ne wala chhe te sagaa nathi (Sometimes blood relations are not your well-wishers, and your well-wishers are not your blood relations).”

The first, red-jacketed Parsi Bol book (with Dolly Mistry also helping with some of the translation), followed by the bright yellow edition, combined to present a total of 1,058 phrases crowd-sourced from 308 contributors. Along with plenty of her own, Rutty Aunty accurately cracked their meanings and had us polish the translations uniformly throughout the pages. Together, we intended the effort as an exercise in chronicling, to preserve the community’s linguistic richness through its signature phrases. Commenting on the timeliness of the publication, actor Boman Irani quipped, “A world without Parsi Bol is as scary as losing the recipes for dhansak and lagan nu custard. We would have lost forever what is unique to us—our humour, our wisdom and our heritage.”

Thanks to Rutty Aunty and other seniors in Sooni’s family, besides a bevy of fuis (paternal aunts) in mine, we may have managed a modest salvaging attempt at documenting these priceless expressions. “Actually, she picked up a lot of phrases from her mother,” Mehernosh says of Rutty Aunty’s prolificity and proficiency.

And what kind of mother was she? “She was one tough lady,” he replies. “Not too strict but always inculcating values. To be strong, to never back off from qualities to believe in, like honesty and forthrightness. She avoided confrontations, was willing to compromise and avoided unpleasantness even if she felt offended or hurt. She remained quite headstrong, though, to her last day. Having undergone many sicknesses, she recovered from cancers, a stroke and a whole host of other ailments. She was all about tenacity.”

In later years, she missed her fix of novels and newspapers, unable to read owing to failing eyesight. With the deafness, this was a huge handicap. She bore them lightly, of course. With stout resolution she made independent phone calls, despite the sad reality of seldom catching the words spoken at the other end of the line. But we knew what hers were.

“I will miss her calls to inform me of the family’s Parsi birthdays,” Sooni says. “She’d start with—‘Soona? Today is your Firdaus’, or Jahan’s or Iyanah’s, ‘roj noo varas’ (birthday according to the Zoroastrian calendar).”

That same thoughtfulness was extended to me on getting to know her. Rutty Aunty would unfailingly wish me and my husband on our special days—with her warm phone tone and loving lilt of voice.

As Sooni asks, “Who will remind us now?”

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at meher.marfatia@mid-day.com/www.meher marfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!