Chronicling the life and times of surgeon par excellence, Dr Rustam Cooper, after whom Cooper Hospital in Juhu is named

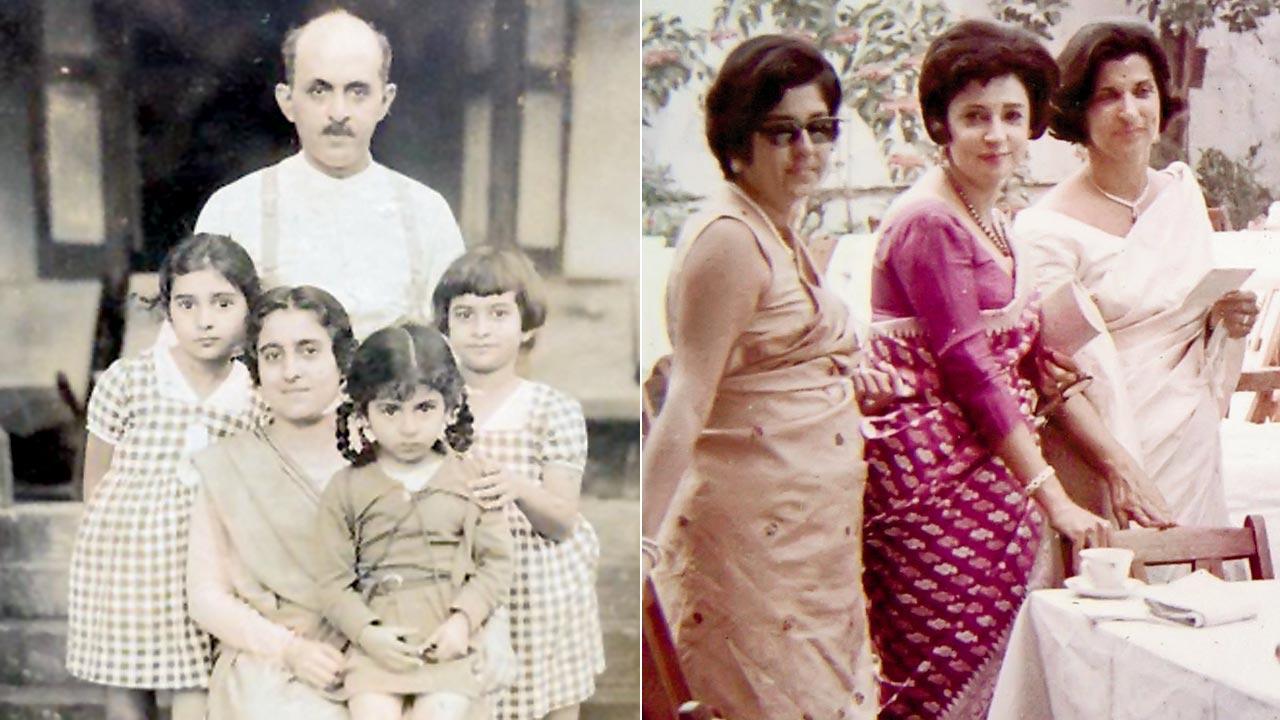

Dr Rustam Nusserwanji Cooper and wife Minnie on the verandah of their home in Cumballa Hill; (top) Dr Cooper, after whom the BMC named the Juhu hospital

He was all things to all persons. His behaviour and approach to the humblest patients, servants and subordinates was the same as to Viceroys, Governors, Maharajas, statesmen and industrialists consulting him,” noted The Bombay Samachar editor Jehan Daruwala in his popular column, Parsi Tari Arsi, for the birth centenary of Dr RN Cooper: April 3, 1993.

He was all things to all persons. His behaviour and approach to the humblest patients, servants and subordinates was the same as to Viceroys, Governors, Maharajas, statesmen and industrialists consulting him,” noted The Bombay Samachar editor Jehan Daruwala in his popular column, Parsi Tari Arsi, for the birth centenary of Dr RN Cooper: April 3, 1993.

ADVERTISEMENT

The surgeon so accomplished that he was flown to Iran en famille to operate on Empress Farah Diba—the Shah offered carpets and gold coins in gratitude—most nobly also slipped small envelopes of money under the pillows of poor patients he treated free. Conducted with quiet generosity, the second kindness was a follow-up to tide them over days of staying home with prescribed bed rest.

It was the only way Dr Cooper knew to work, for which he was widely revered by patients and admired by the medical fraternity. One eminent surgeon told an patient, “If you want an operation done free, go to Cooper, my fee is R5,000.” On another occasion, Dr Cooper was called to Poona for an old and indigent patient. Cured, she insisted on paying. To save her embarrassment, he quoted an oddly precise sum, a few rupees and some annas. When a relative asked how he computed that exact amount, he explained it was his train fare.

There was everything exceptional about the man who lived by the Hippocratic oath and whose sterling contributions the municipal authorities have commemorated with the RN Cooper Hospital in Juhu. “The BMC decided to name the hospital after him, with absolutely no lobbying from the Coopers. Quite to the contrary, it came as a surprise to them,” says family friend Dr Jehangir Sorabjee.

Born to a humble marine engineer, Rustam Nusserwanji Cooper had eight siblings. Shining in science and Shakespeare classes alike at Bharda High School, he went on to earn an MBBS, graduating from Grant Medical College (GMC) and Sir JJ Hospital. Unswerving focus and dedication saw him meticulously dissect as many as 17 cadavers during the initial years alone, with the neatness, skill and speed for which he was soon to become legendary.

Completing his education in England on a government scholarship, he proved an early Indian recipient of the Master of Surgery degree from the University of London and an FRCS. There he struck a lifelong friendship with Dr BC Roy, later Chief Minister of Bengal. Subsequently meeting every year, they collaborated with success on progressive medical research initiatives across the country.

An early photograph with their three daughters; Hilloo Dalal, Gooloo Sethna and Mehroo Dastur at a family navjote in 1970

Ironically, after four years of practice in the best UK hospitals (competent doctors were in demand during the First World War), on his return Dr Cooper was refused appointment at his alma mater GMC, which accepted British surgeons alone. Fortunately, the relatively new Gordhandas Sunderdas Medical College (GSMC) and King Edward Memorial (KEM) Hospital invited him to join as Honorary Surgeon and Head of the Department of Surgery.

In addition, he assumed honorary directorship of Jerbai Wadia Hospital for Children in Parel, was a founder of the Indian Association of Surgeons and became the first Indian to be conferred membership of the American Association of Surgeons. Despite the strain of long professional days, in which he started the Charak Clinic at Charni Road, he willingly spared time to serve on the board of the JB Petit School for Girls and Jai Vakil Foundation running the School for Children in Need of Special Care.

The good doctor groomed several specialists, including doctors NA Purandare, AV Baliga, PK Sen, RG Ginde and Noshir Antia. He taught surgical pathology with passion, precision and humour enough to have admiring students affectionately dub him Daddy Cooper, while he called each Sonny.

Dr Cooper and his wife Minnie parented three daughters, Gooloo, Mehroo (both qualified physicians) and Hilloo. Each named a son Rustam after their beloved father. “Fond of golf, he played at the Willingdon Club with his regular foursome. At Chembur he had a hole-in-one—his name is up there on the board,” says son-in-law Jehangir Dalal. “A truly gentle person, he was a very affectionate father-in-law and wonderful with his grandchildren.”

Recollecting a serene photograph of Dr Cooper sitting in an open field with his dog and an easel, Jehangir’s daughter Meher Dalal says, “Toby, the small hound dog my grandfather loved, was around when he painted watercolours as a hobby. My mother [Hilloo] told us how incredibly hard he’d worked. Studying nights under streetlamps, he understood the expenses and sacrifices parents make for their children.”

In a lighter vein, Meher’s brother Behram says, “I was seven when my grandfather passed away. Later, on a naughtier note, detesting gym, I’d write excuses on his prescription pad sheets my mom had at home, scribble a signature and hand them in. This worked initially. Then I had a terrible instructor ripping them up without reading. When I switched schools, he was replaced by someone more tyrannical nicknaming me Hernia Operation Boy!”

Another granddaughter, Jeroo Ranji, shares, “My mother [Mehroo] used to tell us how Dad Dad, as we called him, tied his shoelaces on both shoes simultaneously by using one hand for each shoe. This story fascinated me as a child and attested to his prowess as a skilled surgeon. He had an innate curiosity in many diverse subjects, created little home movies of his travels, was an avid photographer and enjoyed classical music. Years later, I spent hours at Marshall Lodge, the Cooper residence on Cumballa Hill, combing through his library of National Geographic magazines from decades past.”

Occupying equal pride of place was his eclectic collection of titles on subjects ranging from comparative religious philosophies to biographies of internationally renowned surgeons. Neurosurgeon Sunil Pandya says, “I knew of monthly dinner meetings he organised with teachers and students, and of his enviable collection of books. With the audacity of youth, I wrote to him requesting permission to study them. I was surprised by the prompt, courteous reply inviting me to meet at his Charak Clinic consulting room. He put me at ease and took me around the steel cupboards housing a variety of precious books. I requested an appointed evening hour each week to make notes from books in his balcony. He suggested borrowing them to read at my leisure. Not knowing me from Adam, to place such faith in me with books not easily available in Bombay was humbling. Thanks to his courtesy, I read classic biographies of John Hunter, Edward Jenner and many others.

“Dr Cooper was keen on studying the history of medicine. He felt strongly that we must remain aware of the trials those who have advanced medicine over the millennia underwent and applaud their achievements. I have been fortunate to study his published papers, on subjects from ‘A short history of anaesthesia’ and ‘Medical ethics through the ages’ to purely surgical topics such as epigastric pain and prolapse of the rectum. Though a general surgeon and specialisation was yet to come in, he published papers on ‘Traumatic surgery of the skull’ (1945) and ‘Tumours of the spinal cord’ (1948).”

Dr Cooper was a KEM professor and retired by the time Dr Pandya studying at JJ Hospital entered medicine. Dr Pandya narrates an experience related to him by Dr Cooper’s student, the reputed Dr Tehemton Udwadia. Diligently present half-an-hour prior to any scheduled lecture he delivered, Dr Cooper would write on the hall blackboards, draw illustrations and charts. When students trickled in, he had finished with the necessary text and drawings—“I don’t wish to waste their time. Completing all this before they come, I can spend the full period teaching and emphasising points,” he said.

The staunch freedom patriot was a linguist and scholar of Persian and Gujarati, who even took up learning Russian in his middle age. “Always interested in history, my mother [Gooloo] accompanied him to the Indus Valley, Iran and Japan,” remembers granddaughter Meher Dadabhoy. A lover of walking and hiking, he went up to Duke’s Nose in Khandala where he rented a cottage every year in May. Rolling up his sleeves sportingly, he indulged in games of gilli-danda and nargolio with his chauffeur’s children and locals. An amateur astronomer, he often took them sky-gazing with a telescope.

On April 5, 1966, addressing the 11th Annual Conference of the Bombay branch of the Indian Medical Association, Dr Cooper suffered a critical heart attack. “His funeral was so well attended by all the people he had looked after, that the queue waiting to pay respect came all the way down to Kemp’s Corner and beyond,” says Dr Jehangir Sorabjee. “Clearing his drawers, they found endless blank cheques from folks he did not charge. They probably just wrote them, asking him to fill in whatever fee he wanted. Of course, he hadn’t even bothered to do that.”

As Daruwala concluded in his Samachar column: “The great surgeon and the greater gentleman had walked out into the sunset. But the memory lingers and those in contact with him remember him with adoration and prayer.”

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at [email protected]/www.meher marfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!