The boar as the pig becomes docile. However, if the domestic pig is left out in the wild, it becomes feral. It grows its tusks, its colour becomes brown and black, because of the production of melanin

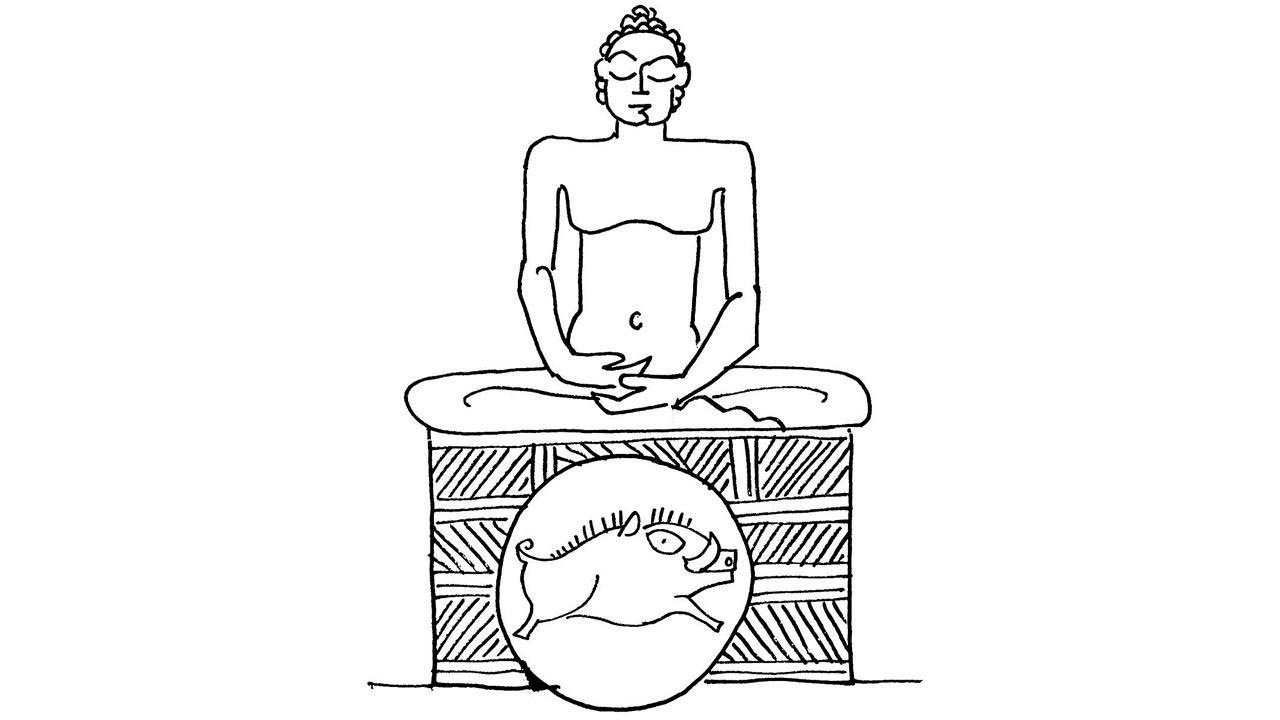

Illustration/Devdutt Pattanaik

Hunting and eating wild swine or pigs was common in ancient India, a sport of kings. Hindus should have no problem with pork therefore. However, pork dishes in India today are linked to either tribal or Christian communities of India, and those with a strong European influence. Pork is a taboo in the Muslim world and may have influenced the food habits of the elite Hindu.

Hunting and eating wild swine or pigs was common in ancient India, a sport of kings. Hindus should have no problem with pork therefore. However, pork dishes in India today are linked to either tribal or Christian communities of India, and those with a strong European influence. Pork is a taboo in the Muslim world and may have influenced the food habits of the elite Hindu.

ADVERTISEMENT

To clarify: when a wild boar is domesticated, it becomes the domestic pig. In a generation or two, it loses its dark colours and its huge curved tusks, that are sharp and that can tear the flesh. The boar as the pig becomes docile. However, if the domestic pig is left out in the wild, it becomes feral. It grows its tusks, its colour becomes brown and black, because of the production of melanin. It then becomes a wild creature that digs out roots for consumption. It is a fierce and intelligent animal.

This wild creature’s ability to dig the earth for roots may have played a key role in its association with agriculture and fertility. This is why, in Brahmana literature, it is said Prajapati takes the form of a wild boar called Emusha. He then raises the earth from the bottom of the waters and places it upon a lotus leaf. This story is later associated with Vishnu.

Vishnu plunges into the sea, kills the asura who has abducted the earth-goddess and brings her to the surface, placing her on his snout, between his gigantic tusks. She embraces him tenderly as they rise to the surface. This lovemaking is the reason why the earth is folded and transformed, into its valleys and mountains. His wild and resplendent horns make the soil fertile and give rise to all the seeds of all the plants in the world. He becomes Bhupati, lord of the earth and Prithvi Vallaha, beloved of the earth. These tiles were loved by kings who saw themselves in the image of Varaha. Hence Varaha images are popular themes in the artwork of Gupta, Chalukya and Vijayanagar kings from 3rd century to 10th century.

In his early Chaturmukha form, popular in Kashmir 1,500 years ago, Vishnu is seen with a lion head on one side and a wild boar on the other. In his Panchmukhi form, Hanuman also has, besides his own monkey head, a wild boar head along with that of a horse, an eagle and a lion. In Tantra, Varahi, or female boar (sow), is a powerful deity related to fertility and power. In Tantrik Buddhism, the wild boar is associated with the goddess of dawn, Marichi. It is said she rides the chariot pulled by seven wild boars, reminding us of the seven wild horses that pull Surya’s chariot. In Jain traditions, Vimalnath is the Tirthankar associated with the wild boar.

All this changed when the Islamic rulers of India saw the pig as dirty, a creature to be shunned. The Sufis who spread Islam into India’s hinterland promoted this belief. Everyone accepted it across caste lines. The pig came to be seen as dirty and connected with the Chandala, the “low” caste people as depicted powerfully in the award-winning film, Fandry.

The author writes and lectures on the relevance of mythology in modern times. Reach him at [email protected]

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!