This year, I visited the Aga Khan Museum (of Islamic art) in Toronto and Islamic art galleries at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Illustration/Uday Mohite

![]() I have been following Dalit, Bahujan and Adivasi films, arts, culture and history since the last eight years. My journey started when I curated The Die is Caste for the Kochi Muziris Biennale in January 2017, with a package of films on Dalit issues, along with music and dance performances by Bahujan, “lower” castes and indigenous people. The films included Nagraj Manjule’s Sairat (Marathi), John Abraham’s Agraharathil Kazhuthai (Donkey in a Brahmin Village, Tamil), BV Karanth’s Chomana Dudi (Kannada) and Bikas Mishra’s Chauranga (Khortha). The performances were by protest singer Bant Singh and Baljit Kaur (Punjab), Manimaranayya, Magizhiniamma, Samaran and Iniyan (Parai artists, Tamil Nadu), and Karinthalakoottam, an indigenous folk troupe (Thrissur, Kerala). The programme was so warmly received, I knew I had touched a chord.

I have been following Dalit, Bahujan and Adivasi films, arts, culture and history since the last eight years. My journey started when I curated The Die is Caste for the Kochi Muziris Biennale in January 2017, with a package of films on Dalit issues, along with music and dance performances by Bahujan, “lower” castes and indigenous people. The films included Nagraj Manjule’s Sairat (Marathi), John Abraham’s Agraharathil Kazhuthai (Donkey in a Brahmin Village, Tamil), BV Karanth’s Chomana Dudi (Kannada) and Bikas Mishra’s Chauranga (Khortha). The performances were by protest singer Bant Singh and Baljit Kaur (Punjab), Manimaranayya, Magizhiniamma, Samaran and Iniyan (Parai artists, Tamil Nadu), and Karinthalakoottam, an indigenous folk troupe (Thrissur, Kerala). The programme was so warmly received, I knew I had touched a chord.

ADVERTISEMENT

In the last three years, I’ve also had the opportunity to expand my interests. In September I attended the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF)—I’ve been Senior Programme Advisor, South Asia to TIFF, and Curator/Consultant to TIFF Cinematheque over the last 13 years. Apart from the festival, I travelled in Toronto and extensively in the US, each year, including New York, Boston or Washington DC, Los Angeles and San Francisco, partly to better understand the arts, culture and history of Black, Native American, Indigenous and First Nations people. I met scholars, activists, filmmakers and curators working in these fields, including on caste-related issues. This year, I met, among others, Dr Suraj Yengde, WEB Du Bois Fellow at Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts. These conversations have expanded my understanding of the history and representation of marginalised people.

I also visited many museums and art galleries showcasing the art, culture and history of Black artists, Indigenous artists and minorities (in some countries), including Islamic artists; erased histories, and art in general. In 2022, I saw three exhibitions in the US that became a turning point in my understanding of how Black, Indigenous and other communities are increasingly using the arts for greater representation, telling their own stories, curating their own shows and rewriting their own histories. It is truly inspiring, and I hope Bahujan communities in India can increasingly do the same. For instance, in New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art had a remarkable exhibition, Before Yesterday We Could Fly: An Afrofuturist Period Room. The idea of Afrofuturism is very appealing as a vision for the marginalised; it is a cultural aesthetic of the African diaspora exploring, as author Ytasha Womack describes it, “an intersection of imagination, technology, the future and liberation.” In Washington DC, I saw how the National Museum of African American History and Culture distilled centuries of Black history into an immersive and deeply moving experience. Then in Los Angeles, I went to the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures’ seminal exhibition, Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898-1971, that examined the Black contribution to American cinema. At each, I observed what the curators chose to focus on, how they displayed the exhibits, and how the public interacted with them.

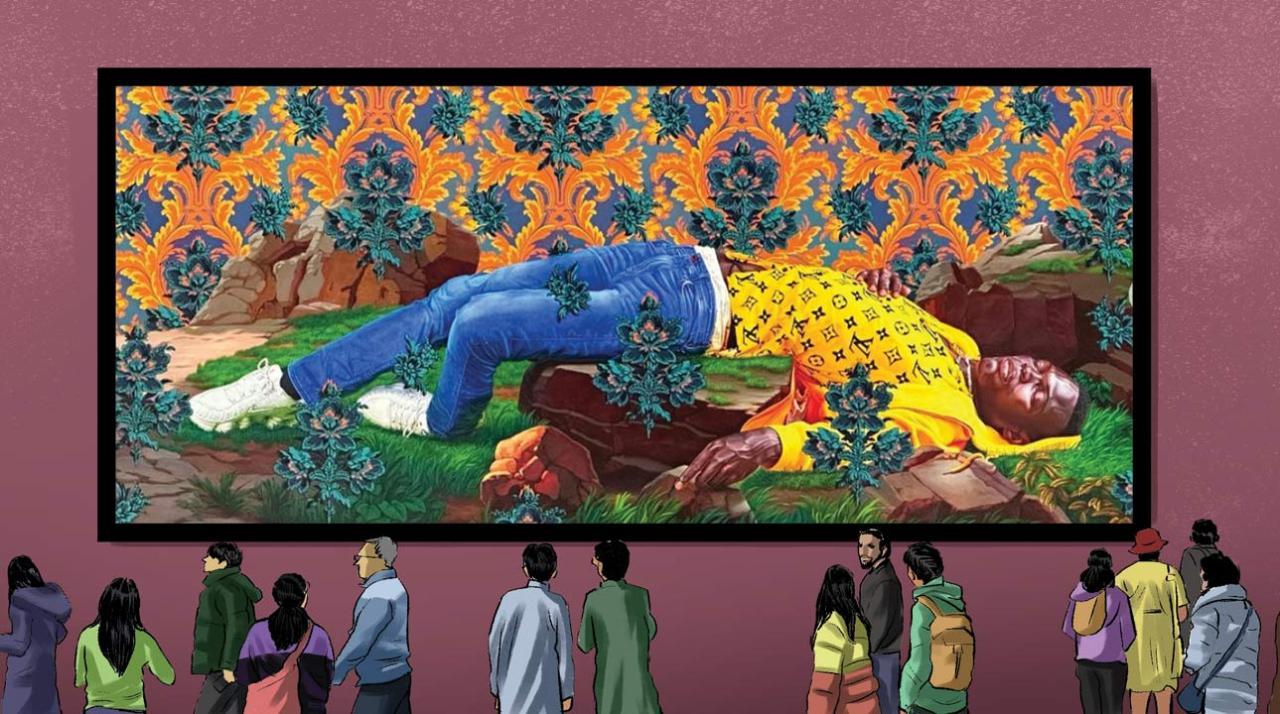

This year, I visited the Aga Khan Museum (of Islamic art) in Toronto and Islamic art galleries at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. In Los Angeles, I visited the California African American Museum, CAAM (superb, including the work of Simone Leigh and George Washington Carver). I also spent time at the Getty Museum and Academy Museum, showing Hollywoodland: Jewish Founders and the Making of a Movie Capital, and more. In San Francisco, I visited the de Young Museum, that last year, had shown Kehinde Wiley: An Archaeology of Silence, as the Black artist confronts the silence surrounding the systemic violence against Blacks through the fallen figure. One of his famous works, for instance, is called Femme Piquée par un Serpent (Woman Bitten by a Snake)/ (Mamadou Gueye), that refers to a famous marble sculpture of the same name by Auguste Clésinger in Paris, with a violently contorted, fallen, nude woman, bitten by a snake. In contrast, Wiley’s painting of the fallen man is a “powerful elegy of resistance.” This time, at the de Young Museum, I saw Leilah Babirye’s show, We Have a History, with powerful sculptures from trash by the Ugandan, Black, queer artist; and more at the San Francisco MOMA, SFMOMA, and Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, BAMPFA in Berkeley. There, I also met Barnali Ghosh who, with Anirvan Chatterjee, conducts the Berkeley South Asian Radical History Walking Tour. All in all, a fully paisa vasool trip. Phew!

Meenakshi Shedde is India and South Asia Delegate to the Berlin International Film Festival, National Award-winning critic, curator to festivals worldwide and journalist. Reach her at meenakshi.shedde @mid-day.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!