Engaging stories surround Hindi film hits and other evocative songs in diverse Bombay locales

Amitabh Bachchan’s Anthony Gonsalves character was based on a bootlegger Manmohan Desai knew in his younger years in Khetwadi

Mapping neighbourhoods can prove as much an emotional ride as it is a factual quest. If, of course, one chooses to let it. Among the many joys that research for these pages brings are anecdotal accounts of movie scores seeded in a particular place or from a specific situation. The circumstances, fortuitous or otherwise, inspiring a lyric or music sheet. Here are some stories mirroring the moods behind popular melodies, the kind of rigour they required and adulation they stirred.

Mapping neighbourhoods can prove as much an emotional ride as it is a factual quest. If, of course, one chooses to let it. Among the many joys that research for these pages brings are anecdotal accounts of movie scores seeded in a particular place or from a specific situation. The circumstances, fortuitous or otherwise, inspiring a lyric or music sheet. Here are some stories mirroring the moods behind popular melodies, the kind of rigour they required and adulation they stirred.

While profiling the Mehta family’s trio of Marine Drive buildings—Zaver Mahal, Kapur Mahal and Keval Mahal—I discovered an interesting angle to the lilting tune of “Tadbeer se bigdi hui taqdeer bana le”, from Navketan’s 1951 thriller, Baazi. SD Burman and his son RD Burman lived briefly at Zaver Mahal before shifting to Sea Green Hotel till their Bandra bungalow was ready. Tapping out the ghazal-turned-jazz beat in this home, an excited SD asked Guru Dutt, who is supposed to have fallen for singer Geeta Roy while she recorded this song, to come and hear his arrangement. Its second line, “Apne pe bharosa hai toh ek daao laga le (If you believe in yourself, take a chance)”, with which guitar-strumming Geeta Bali tempts a shy Dev Anand, seemed to echo the plucky spirit of the Mehta patriarchs whose rags to riches adventures have been narrated on these pages.

ADVERTISEMENT

Dev Anand singing “Khoya khoya chand...” in Kala Bazar, 1960. The legendary lyricist Shailendra was suddenly inspired to write this SD Burman-scored hit on a full moon night on Juhu beach. File pic

Dev Anand singing “Khoya khoya chand...” in Kala Bazar, 1960. The legendary lyricist Shailendra was suddenly inspired to write this SD Burman-scored hit on a full moon night on Juhu beach. File pic

nother SD Burman-Dev Anand collaboration was ignited on a moonlit night in 1959 by the romantic balladeer, Shailendra. He suffered major writer’s block before the lyricism of “Khoya khoya chand…” flowed, with its subsequent picturisation on Dev Anand and Waheeda Rehman, in the Ooty valleys for Kala Bazar released in 1960. It was the first time SD Burman was collaborating with a lyricist new to the Navketan banner. He was ready with a last composition, for which Shailendra lacked words to match. The senior Burman instructed son RD not to return from Shailendra’s home without the song. Shailendra drove broodily to Borivli National Park where, instead of inspiration, the only thing striking were his matches. Puff upon puff of cigarettes, no sign of a line. With darkening skies, he thought a change of scene could do the trick. Strolling the deserted Juhu beach, Shailendra asked RD for a fresh matchbox. On a crumpled cigarette pack foil piece, he scrawled the mukhda he found himself softly crooning: “Khoya khoya chand, khula aasmaan/Aankhon mein saari raat jaayegi/Tumko bhi kaise neend aayegi”.

At Ganesh Prasad on Sleater Road, I met the family of Bharatanatyam doyen Guru Parvati Kumar, who shaped the career of exponents including Sandhya Purecha and choreographer PL Raj. A Parel municipal school dropout, he earned mill worker wages and recreated Uday Shankar’s ballet poses for Ganpati pandals. Learning classical dance, he moved to Ganesh Prasad, teaching from the room where I chatted with his gentle wife Sumati. Their cricket coach daughter Aparna shared a video clip of her mother swirling at 16 to “Suhana hain yeh mausam” from Zia Sarhadi’s film, Footpath. “I longed to dance under Raj Kapoor’s direction,” the octogenarian said. She did, in the evocative dream sequence of Awara. Content with one-third the fee, compared with the Footpath song getting her R600, with which she painted her Sonawala Building home round the corner in Tardeo.

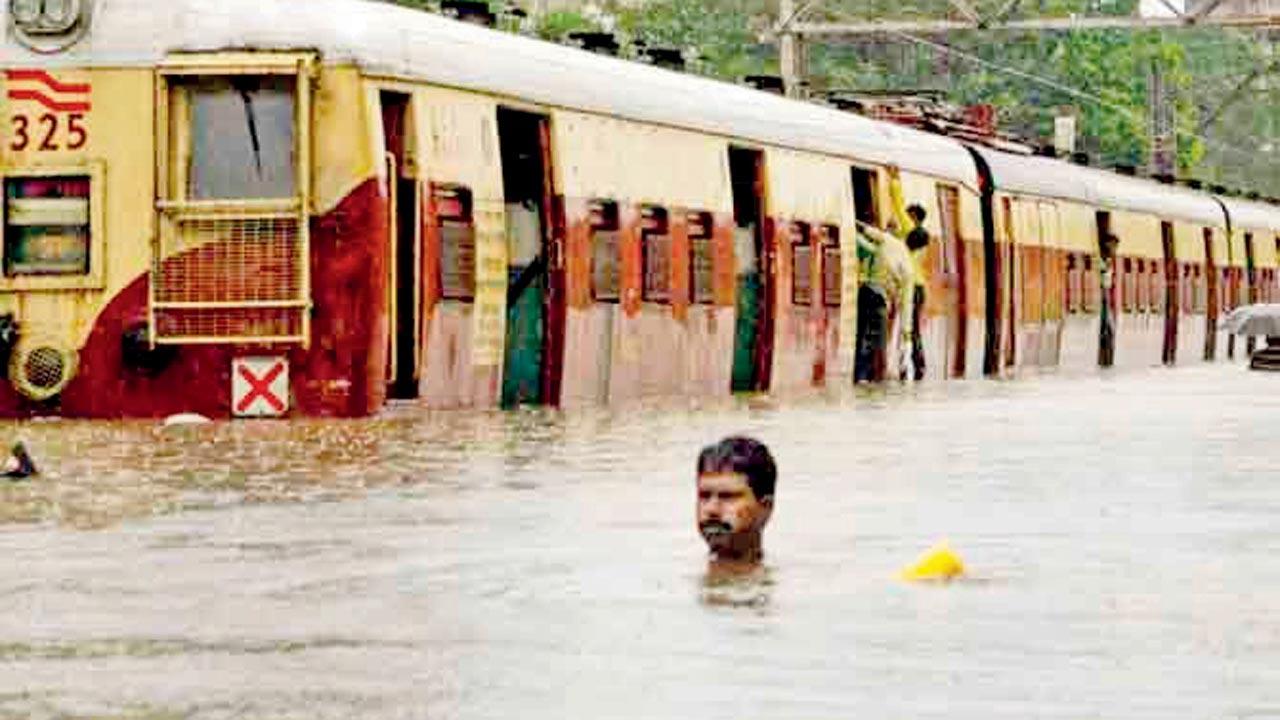

After the flood fury of July 2005

After the flood fury of July 2005

An engaging Raj Kapoor-related story sprang from Bhendi Bazar, near the Mohammed Ali Road-Mandvi junction, where Dilip Kumar had resided in his childhood, growing up next door to Farida, the mother of Tarannum Khan whom I chanced to interview. Her father, Mohammed Ilyas Khan of Bhopal, became Saira Banu’s secretary. Farida’s father, Urdu theatre doyen Dr Abdul Alim Nami, was also the Censor Board president. “Raj Kapoor visited my nana, pleading that he shouldn’t cut ‘Bol Radha Bol’ from Sangam,” Tarannum said. The 1964 song showed Kapoor woo Vyjayanthimala in a red swimming costume. Leading ladies did drape wetsuits, but this was perhaps a bold colour-era first. Retained, the Mukesh number proved one of Shankar-Jaikishan’s most widely hummed numbers.

On Queens Road it was revealed that Dilip Kumar and Meena Kumari came to Edena building to visit Dr VN Sinha, producer of the 1960 action caper Kohinoor. Depressed by repetitive Devdas-type routines, Dilip Kumar was being advised to essay lighter leads, as in this swashbuckler saga. To authenticate Naushad Ali’s composition, “Madhuban mein Radhika naache re”, the matinee idol learnt the sitar and played a solo on the instrument. Surely, his tragedy-inclined heroine must have smiled at that too.

Usha Uthup and Adi Pocha’s soulful ballad repurposed the 1969 hit “Bombay meri hai”, originally sung by Usha’s sister Uma Pocha. File pic

Usha Uthup and Adi Pocha’s soulful ballad repurposed the 1969 hit “Bombay meri hai”, originally sung by Usha’s sister Uma Pocha. File pic

Certain addresses exude remarkable musical energy. It was so at 27 Pedder Road, in Asha, the 8,000-square foot ancestral bungalow of filmmaker Vikas Desai, where Ganesh celebrations were traditionally monumental. From 1956, when his musician uncle Vasant Desai lived there, devotion to Bappa the Benevolent was marked by mellifluous mehfils. The ambience of the bungalow was enhanced quite differently by the feted composer. Over 200 people sat on gaddis, enchanted by the consummate artistry of Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Amir Khan, Salamat Ali and Nazakat Ali Khan, Vasantrao Deshpande and Abdul Halim Jaffer Khan. Classically committed in a chimerical industry, Vasant Desai laced lilt with soul for cinema doyens like his guru, V Shantaram. The maestro set to suspenseful music, Shaque, his nephew’s debut thriller. “From the age of five, I was present at meetings my kaka had with leading poet-lyricists,” said Vikas, whose concert duties included standing to welcome guests at the Asha gate up to 1.30 am. He remembers serving Bismillah Khan’s troupe water and tea throughout the rehearsals for Goonj Uthi Shehnai in one of Asha’s massive halls.

The rousing public reception to a composition can, no doubt, upstage any origin story. “What unparalleled cinema history was created in 1975,” declared Sanjay Vasawa, former manager of Edward Theatre in Kalbadevi. He meant the months of Jai Santoshi Maa’s reign which catapulted to superstardom a heavily adorned and adored Anita Guha essaying the eponymous role. Her idolisation, verging on worship, asserted how the belief system of the janta shaped the city’s social fabric. Clapping, crying and chorusing bhajans, repeat audiences created a dream year for Edward. Fervent fans folded hands in tearful prayer to strains of “Main toh aarti utaaru re Santoshi Mata ki”. Vasawa added, “Thousands thronged here, jumping queues and pressing noses against the ticket window. Treating the cinema hall like a local temple, Gujarati and Maharashtrian housewives removed their chappals at the threshold. Carrying puja thalis in their hands, they entered barefoot, lit diyas when Devi Maa appeared on screen, and distributed chana and jaggery to other devotees.”

Extensively photographing the last surviving single screen cinemas across the country, Hemant Chaturvedi provides an amusing aside indicative of the extent to which crazed audiences take the mania for chartbusters. Burning with film fever, members of the Stalls would often leap up, whistling and hooting while gyrating boisterously in the aisles. They also exercised a strange control, never going to the loo during a song sequence—“They believed the film flopped if anyone left to pee then. Holding it in ensured a hit!”

A bootlegger, who made a familiar figure in the maze of Khetwadi gullies, unwittingly provided the catchy notes of possibly the most fun nonsensical ditty in a Manmohan Desai flick. “It is thought my heroes are unbelievable, but so are people,” the lord of the lost-and-found formula famously said about Amar Akbar Anthony. The last was based on this real-life character who’d loudly declare, “Kya man, Desai, tum toh apun ka bhai hain”—lingo that fit Anthony Gonsalves tight as the white gloves he wore, popping nattily out of the giant Easter egg for the “My name is Anthony Gonsalves” track. Transplanted to a tonier SoBo street, Manmohan pined for his home mile and rode back to Bhajekar Lane in a lorry.

Speaking of firm-rootedness. A song not cinematically born—yet hard to ignore in these months of monsoon mayhem, pothole-induced accidents and tragic building crashes leaving hundreds homeless—is the sensitively reworked version of a peppy picnic standard. After the July 2005 deluge, the beat changed for soaring strains of “Bombay meri hai”, sung in the ’60s by Uma Pocha. Riffing off that chirrupy take on the city, her sister Usha Uthup slowly intoned: “Even when it rains, we just roll our sleeves and say/Come to Bombay, come to Bombay, Bombay meri hai.” And “People come from everywhere, from near and afar/To make a decent living or to be a superstar/They decide to stay and one day you will hear them say/Come to Bombay, come to Bombay, Bombay meri hai.” A paean to the kindness of strangers and to adaptability, the wistful soundtrack wafted over actual reportage that captured crippling floods, interspersed with visuals of policemen, dabbawalas and taxi drivers rescuing pedestrians stranded in neck-high water. The old classic filled with new meaning in this poignant rearrangement by Zubin Balaporia, the same song evoking an entire other mood. Inexplicable pride. Love for a complete melting-pot of a city. Faith in an indomitable people’s solidarity and strength.

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at [email protected]/www.meher marfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!