The involvement of Brahmins in the betrayal of Chhatrapati Sambhaji is papered over by those who demonise the Mughal emperor, hoping new villains from history are not found as it would divide Hindus

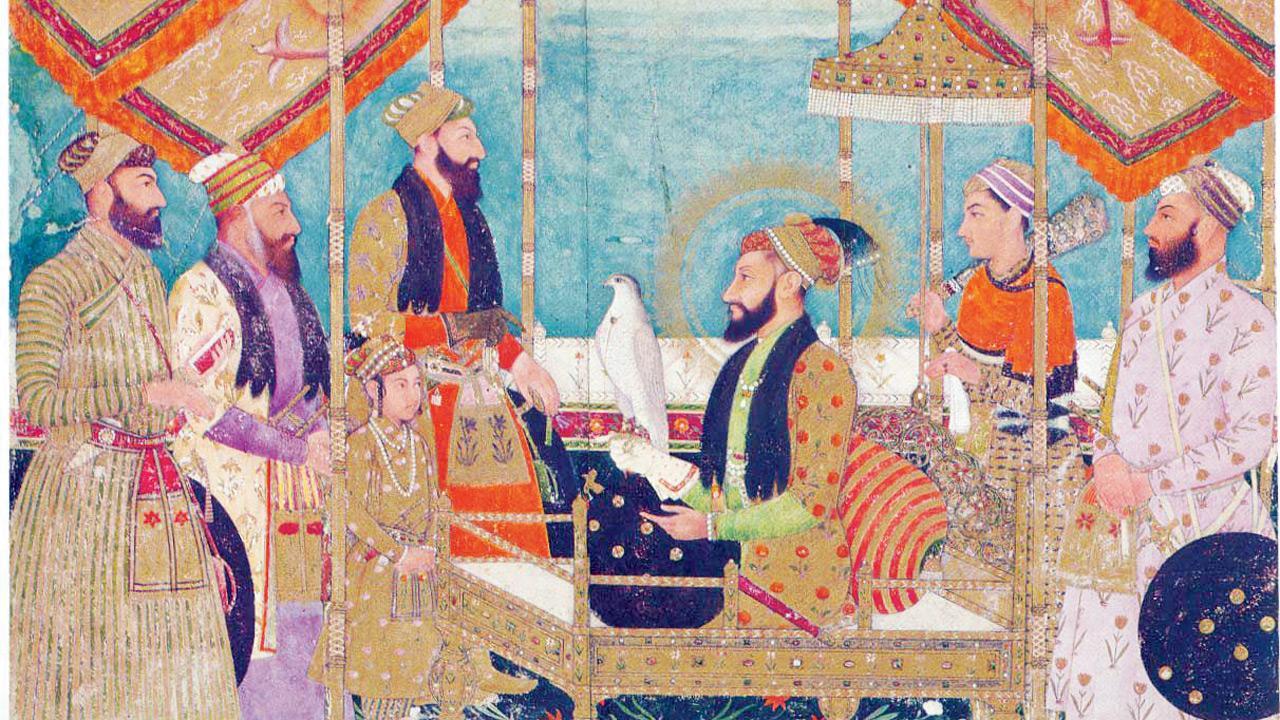

A painting of Aurangzeb seated on a golden throne. PIC/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Marathi historian Indrajit Sawant enraged quite a few in Maharashtra with his criticism of Chhaava, a biopic of Chhatrapati Sambhaji, the Maratha king who was betrayed to the Mughals at Sangameshwar, nabbed with his minister Kavi Kalash, and executed on Aurangzeb’s order, on March 15, 1689. In an interview to a YouTube channel, Sawant said Sambhaji’s hideout was disclosed to the Mughals by Brahmins, not the Shirke-Maratha clan, as Chhaava depicts.

Marathi historian Indrajit Sawant enraged quite a few in Maharashtra with his criticism of Chhaava, a biopic of Chhatrapati Sambhaji, the Maratha king who was betrayed to the Mughals at Sangameshwar, nabbed with his minister Kavi Kalash, and executed on Aurangzeb’s order, on March 15, 1689. In an interview to a YouTube channel, Sawant said Sambhaji’s hideout was disclosed to the Mughals by Brahmins, not the Shirke-Maratha clan, as Chhaava depicts.

ADVERTISEMENT

Sawant allegedly received a call from one Prashant Koratkar, who hurled casteist slurs on Sawant for implicating Brahmins in the treachery against Sambhaji. He also challenged Sawant to tell the world what academic James Laine wrote in his book Shivaji: Hindu King in Islamic India, which had created a furore in 2004. A case has been filed against Koratkar.

Indeed, the controversy over Hindutva groups’ demand to demolish Aurangzeb’s grave at Khuldabad serves the purpose of papering over the conflicting Brahmin-Maratha claims about who betrayed Sambhaji. I dive deep into Maratha history to unravel the plot against Aurangzeb, so to speak.

Sawant’s claim that Brahmins betrayed Sambhaji is based on Memoirs of Francois Martin, [French] Founder of Pondicherry, extracts of which are in Jadunath Sarkar’s House of Shivaji. Martin notes that Brahmin ministers secretly asked the Mughals to position troops at a spot in Sangameshwar, where Sambhaji was enticed to go on a hunt. He was ambushed and captured.

Yet, surprisingly, Sarkar, in The History of Aurangzib, Volume IV (1930), names the Shirkes for organising the “ambuscade,” without explaining why he set aside the version of Martin, a contemporary of Sambhaji. Sarkar, nevertheless, writes of repeated attempts of Sambhaji’s ministers to overthrow him. Martin identifies these ministers to be largely Brahmin, who considered Sambhaji as their “declared enemy” and opposed his accession to the throne, in July 1681.

A month later, there was an attempt to kill Sambhaji. Sarkar narrates the story: A boy fed his servant and a dog from a dish of fish prepared for Sambhaji. Both of them died. The boy’s warning saved Sambhaji, who found that the plot to poison him was masterminded by Annaji Datto, a Brahmin minister, who had been granted clemency weeks ago.

Annaji acted in tandem with 20 other officials and seemingly enjoyed the consent of Soyra Bai, Sambhaji’s stepmother. Not all the conspirators were Brahmin, but with Annaji playing the lead role, the plot to assassinate Sambhaji was and is still viewed as Brahminical.

Sambhaji had most of the conspirators bound in chains and trampled upon by elephants. Yet the conspiracies against Sambhaji didn’t abate. This was why, in October 1684, Gangadhar Pant, Vasudev Pandit, Sahuji Somnath—Brahmins, all—and Manoji More, whose caste identity is ambiguous, were “confined until death.” In 1689, Sambhaji arrested Prahlad Niraji, a Brahmin, for instigating the Shirkes to rebel. After crushing the rebellion, Sambhaji retired to Sangameshwar.

Martin writes that to some of Sambhaji’s leading Brahmin officers, a secret compact with the Mughal emperor’s officers “appeared less criminal than carrying out of the murder themselves.” Perhaps they feared alienating the Maratha populace. This was how the seeds of hatred were sown against Aurangzeb, now in full bloom.

All contemporary accounts agree that Sambhaji was brutally executed on Aurangzeb’s order, but differ in their explanation for his decision. Saqi Mustaid Khan in Maasir-i-Alamgiri, completed three years after Aurangzeb’s death in 1707, says Sambhaji was blinded because he had escaped with Shivaji, in 1666, from Mughal custody. And then again, in 1678, Sambhaji crossed over to Mughal general Diler Khan, only to return to Chhatrapati Shivaji later. Aurangzeb presumably didn’t want the intrepid Sambhaji to escape again. He and Kavi Kalash were subsequently “executed by the sword,” Saqi says.

The story becomes ghastlier with time, testifying to historical narratives being constantly rewritten. Ishwar Das Nagar’s Fatuhat-i-Alamgiri, written four decades after Saqi’s magnum opus, says Aurangzeb became miffed with Sambhaji because of his refusal to disclose where his wealth was concealed and the identity of Mughal officers with whom he would secretly correspond. Instead, Nagar writes “that haughty man opened his mouth in shameful and vain words about his majesty.” Aurangzeb, in pique, ordered Sambhaji to be blinded by driving “nails into his two eyes.”

Thereupon, Sambhaji refused to take food. On hearing about his defiance, Aurangzeb ordered Sambhaji’s limbs to be hacked one after another. His “severed head was publicly exposed” in the Deccan and “taken to Delhi and hung on the gate of that city,” Nagar writes. Martin, too, notes that he heard Sambhaji’s head had been publicly displayed at Golconda.

There’s another backstory: After Prince Akbar rebelled against his father Aurangzeb, he took refuge with Sambhaji, inviting the Mughal’s wrath. The brutality of Aurangzeb’s vengeance against Sambhaji differed only in degrees from that the latter administered to Annaji Datto. For an era in which no quarter was given to rivals, would it make sense today for Hindutva groups to demonise Brahmins for betraying Sambhaji? Or for them to decry the king who cruelly killed Brahmin ministers centuries ago? But hating Aurangzeb makes sense, for, otherwise, new villains might be unearthed from history—and their communities loathed, thus undermining Hindutva’s Hindu unity project.

The writer is a senior journalist and author of Bhima Koregaon: Challenging Caste

Send your feedback to mailbag@mid-day.com

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!