We may rejoice at Priya Ramani’s acquittal in the defamation case, but we are not free unless everyone oppressed is free. Our work is never done until we have arrived at a space of truly reparative justice

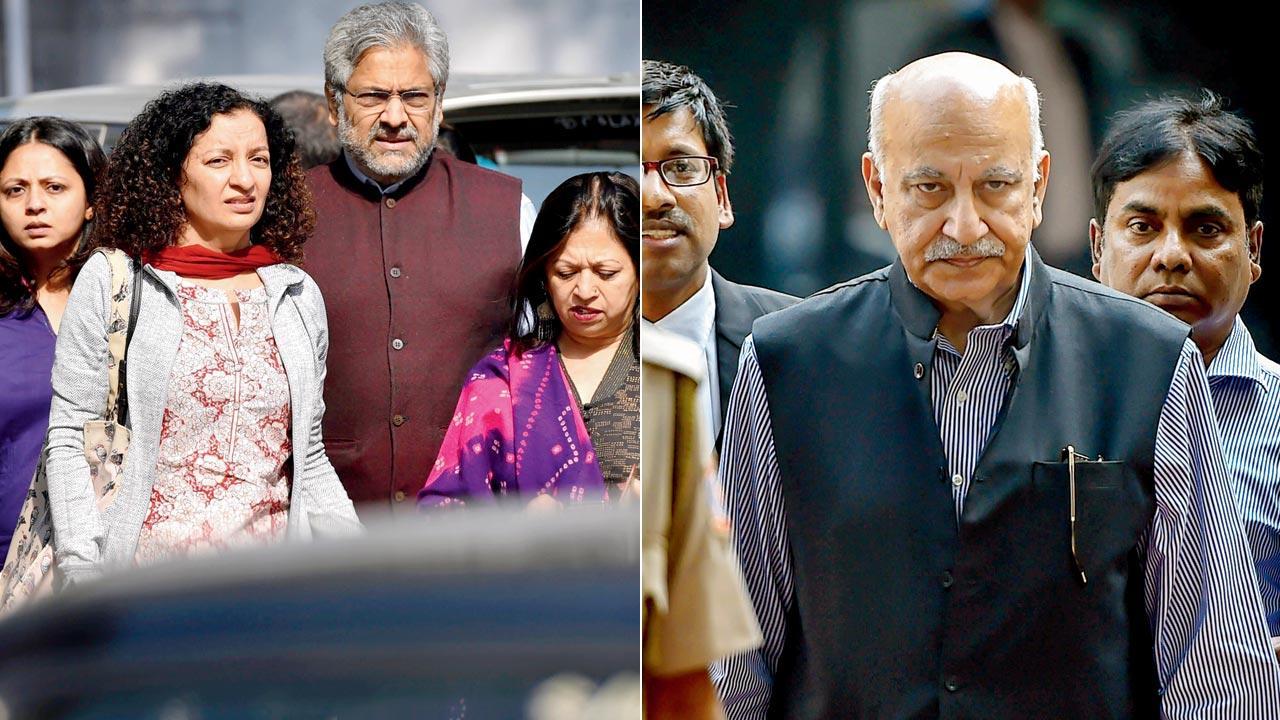

Journalist Priya Ramani was dragged to court by M J Akbar (right) in a defamation case after she accused him of sexual misconduct

In the first week of January 2021, a teacher couple from South Tyrol went missing. Whether I have wanted to or not, I have had to follow news about their disappearance regularly. It’s either on the daily broadcast or in the newspaper. There was the possibility that their bodies were thrown into the river. An elaborate search began.

ADVERTISEMENT

Weeks later, the womxn’s (*) lifeless corpse was found. The son remains under suspicion. His father’s body remains missing. There is some comfort to be drawn from the fact that authorities continue looking, that their search doesn’t seem, yet, to end. My family here tells me that according to the law here, there needs to be a body in order for a person to be convicted of murder.

I wonder sometimes what it would be like if in India there could be similar levels of attention to the unspeakable violence enacted upon womxn, trans and Dalit bodies. Given that so many of these atrocities are state-sanctioned, would the public scrutiny lead to a decreased crime rate? Sometimes I feel sure that so much of the systemic violence is enabled by a populace that has lost touch with its critical faculties. We’re like a nation of zombies; the only ones who are still alive are the people actually fighting on the streets, the farmers staging their protest against everything that is at stake, and risking it all for themselves and for the rest of the country that doesn’t seem to care enough, or is privileged enough to cast judgement.

On Wednesday, as my Facebook and Instagram wall erupted into frenetic celebration of Priya Ramani’s acquittal in the defamation suit that had been slapped against her by MJ Akbar, instead of joining in, I found myself suddenly puzzled by the whole affair. Yes, it was unarguably momentous that she was found not guilty. But given all the testimony that had been supplied by womxn he had molested, what happens to him? Is there no price that he must pay considering everything he put so many womxn through?

When one takes time off to pause and reflect on the meaning of the case and the language of the ruling, it’s hard not to feel angry. At the end of two years of fighting, is this all we achieved—the court’s recognition that a womxn has the right to speak out against an abusive act even years later, and that a man’s reputation doesn’t protect him from being called out for abuse? It really feels like something that should have been so basic, should have been a given. If anything, we should be ashamed. I’m so tired of celebrating when the ‘law’ is upheld, especially because so much of the violence against womxn and oppressed castes is sanctioned by the legal frameworks. It is often punitive towards the marginalised. I remember clearly how afraid womxn were of the defamation suit filed by a celebrated upper caste male Indian artist, and the resistance many had towards speaking out. In a way, this case sets precedent, but primarily for womxn who have the resources to take on a fight.

The premise of feminism is simple. Empowered womxn empower other womxn. This also means that we are not free unless everyone oppressed is free. It binds our personal salvation to that of womxnkind. In that sense, our work is never done until we have arrived at a space of truly reparative justice. This means that we have to be alert and critical at all times, especially in moments where we feel elated about victories. It means we need to continually keep ourselves in check, never take even our own positions for granted, and that we constantly examine our biases and our prejudices and work to do better and be better. It is exhausting, because our triumphs are often quite few, and can be easily overturned in a country full of bigoted Brahminical patriarchs.

Our battle is inter-generational. And, tragically, given the scale of atrocities against womxn’s bodies, particularly Dalit womxn’s bodies, we cannot afford to pause. We must always find ways of resisting the way the mainstream normalises caste atrocities. It is on all of us to ask for better governance, to demand it by virtue of us believing in the equality our citizenship rights affords us. The moment we look at developments more critically, the more obvious it becomes how our rights are being pitted against us. We must never allow caste and class hegemonies to divide feminist interests. We have to work harder so that our sisterhood evolves into something radically intersectional, so that our outrage or joy is not limited to the defeats or triumphs of some categories of womxn. Self-work is thus urgent and lies at the crux of feminist practice.

There is immense reward in all this critical reflection, because living a feminist life involves daring honesty, self-love, and empathy towards oneself and towards others. But the flip side is understanding that we are signing up for relentless intellectual, emotional and spiritual labour. We must learn to practice equality in what enrages us, transform this rage into a fuel, without losing sight of our joy.

* The word womxn is the most recent of several alternative political spellings of the English word woman. It is used to avoid perceived sexism in the standard spelling and to be inclusive of transgender women and nonbinary people.

Deliberating on the life and times of Everywoman, Rosalyn D’Mello is a reputable art critic and the author of A Handbook For My Lover. She tweets @RosaParx

Send your feedback to mailbag@mid-day.com

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!