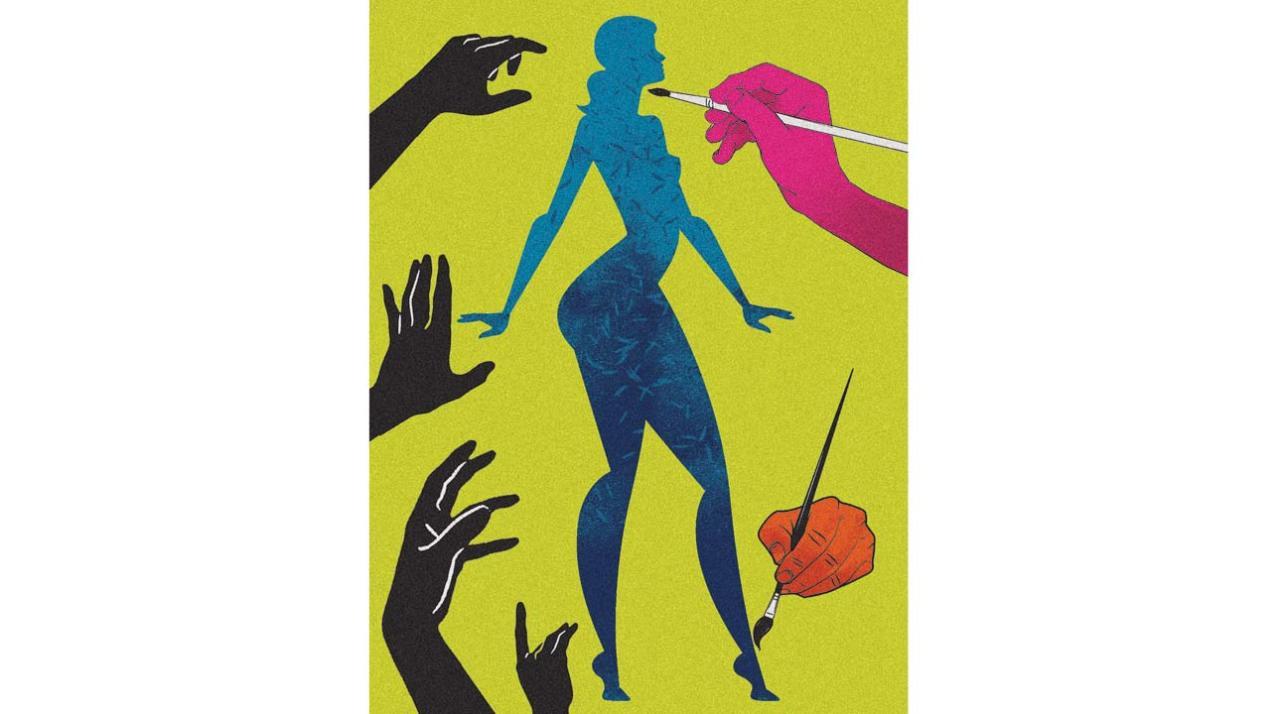

It was a powerful image, bubbling with many meanings of the body and politics. Meta decided its nudity had only one meaning and that meaning was “bad”

Illustration/Uday Mohite

![]() I have often wondered why it’s called the “Customs” Department. Recently, Bombay customs decided to clear my doubts, when they confiscated some artworks by FN Souza and Akbar Padamsee being brought from London, deeming them obscene. The paintings had the kind of names— Nude, Lovers—that give some people conniptions. No other word will do but this one which arrives shuddering, shivering Shiva Shiva and declaring, I must uphold customs and destroy these paintings.

I have often wondered why it’s called the “Customs” Department. Recently, Bombay customs decided to clear my doubts, when they confiscated some artworks by FN Souza and Akbar Padamsee being brought from London, deeming them obscene. The paintings had the kind of names— Nude, Lovers—that give some people conniptions. No other word will do but this one which arrives shuddering, shivering Shiva Shiva and declaring, I must uphold customs and destroy these paintings.

ADVERTISEMENT

Quite like that other customs department, controlling the circulation of images, not goods: social media Community Standards, with which I am intimately acquainted.

I run a platform called Agents of Ishq. It is an arts-based exploration of the worlds of sex and love, and we curate an ongoing conversation on sexuality. Part of this education, for each of us, involves understanding multiple meanings and expressions of bodies, desires and relationships. The role of art-popular or rarified, ancient or contemporary—in surfacing these many meanings is vital, because it allows us to dwell in ambiguity, to make many meanings in our own ways, without imposing any one meaning.

Social media, like authorities, abhors an ambiguity. In the ten years of our existence, its restrictions have multiplied. At first drawings of naked bodies were acceptable. Photographs were not. Later drawings of naked bodies could not be promoted because they were seen as “soliciting sex”. Then, sex-education posts (no bodies involved) were allowed as long as they don’t “promote pleasure”—just lying back and thinking of nation and patriarchy then. One day, Facebook unilaterally removed a post from my feed, deeming it obscene. It was an image by the African American artist Nona Faustine, who photographs herself naked in historic slavery sites. It was a powerful image, bubbling with many meanings of the body and politics. Meta decided its nudity had only one meaning and that meaning was “bad”.

Most of Meta’s guidelines are presented as being for women’s safety (yaniki it’s for your own good). Much like the UP Women’s Commission, which has sent guidelines to all district magistrates that men should not be hairdressers, gym trainers or tailors to women—for women’s safety. While some people may feel safer with service providers of their own gender, other mechanisms can provide this choice. This is not about women’s safety but categorising inter-gender touch outside marriage, as “bad touch”.

The Court scolded the Customs department, which is always fun. But the declaration that art is not obscenity, and experts can help decide this, leaves the idea of obscenity undisturbed. By attributing wrong-ness to the body, we deflect attention from the wrong-ness of action of the violence of a gaze. By making all touch sexual and all sexual touch wrong, we obscure the different meanings of touch, and the contextual nature of consent ( I may be ok touched by someone professionally, but not sexually)—or even the violence of not-touching aka untouchability.

What does a body mean and who decides that meaning? Who assigns your body as worth injuring, dismissing, killing? Or not worthy of desire, healing, justice? The desiring body, the labouring body, the hurting body, the dead body– the 100 meanings of the body, need a hundred ways of understanding meaning. Expressions of the body—burlesque, art, selfies, naked protests, PDA, gender expression and much else—assert this right to interpret one’s body. Without this acknowledgement, what safety can we know?

Paromita Vohra is an award-winning Mumbai-based filmmaker, writer and curator working with fiction and non-fiction. Reach her at [email protected]

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!