I am invested in perpetuating the legacy of feminists of colour from previously colonised or colonised spaces whose advocacy disrupted the whiteness of second-wave feminism

To say ‘third world feminism’ is to situate political ideology beyond the Anglo-Saxon world and to recognise the contributions of feminists of colour. Representation pic

I didn’t think twice about qualifying myself as a third world feminist when I was recently asked to describe my approach towards an artwork I was evolving for an institution in South Tyrol. I had been enlisted to help the curator with writing the captions for certain specific works of art in an upcoming exhibition that dealt quite squarely with systemic racism, queer rights, gender violence and xenophobia. In addition to offering context to each work, the curators were keen for me to also include a perspective. I felt unsure about such an undertaking, because layering perspective within wall caption text could make the experience of reading it overly dense. I have a personal dislike for excessively long wall captions at art shows. I prefer for the texts to be snappy and offer just enough information as to make the art accessible. I feel repelled when a text tells me how to experience a sculpture, painting, or installation. I proposed recording an audio guide that could be made available via QR Code. Visitors could, therefore, choose to listen to my impressions about the exhibition either while in the gallery, or at home, or while driving… The QR Code made the piece site-specific without binding it to the location.

I didn’t think twice about qualifying myself as a third world feminist when I was recently asked to describe my approach towards an artwork I was evolving for an institution in South Tyrol. I had been enlisted to help the curator with writing the captions for certain specific works of art in an upcoming exhibition that dealt quite squarely with systemic racism, queer rights, gender violence and xenophobia. In addition to offering context to each work, the curators were keen for me to also include a perspective. I felt unsure about such an undertaking, because layering perspective within wall caption text could make the experience of reading it overly dense. I have a personal dislike for excessively long wall captions at art shows. I prefer for the texts to be snappy and offer just enough information as to make the art accessible. I feel repelled when a text tells me how to experience a sculpture, painting, or installation. I proposed recording an audio guide that could be made available via QR Code. Visitors could, therefore, choose to listen to my impressions about the exhibition either while in the gallery, or at home, or while driving… The QR Code made the piece site-specific without binding it to the location.

ADVERTISEMENT

Since I’ve been thinking about art criticism as the consequence of metabolising art, thus prioritising the body’s emotional and physiological registers, it was important for me to be transparent about my position. In fact, I believe it should be standard practice for any form of authorship. I think it is an act of consideration towards the reader or viewer, allowing for transparency. I wanted to summon the brownness of my body within the viewer’s imagination and to also suggest that I do not ‘belong’ to this context in which the work is being shown but come from elsewhere, and so observe things differently.

To mark my feminism as third world was to say that this is the lens through which I engage with the politics of the everyday. But the curators did not ‘get’ the various nuances crouched within the ‘third world’ signpost. They were justifiably worried about how it didn’t translate well into either German or Italian, the primary language of the audiences here. I was told that ‘third world’ was an outmoded descriptor. My partner agreed that the ‘first world’ no longer thought it polite to either refer to themselves or be referred as such. I could see how it might be embarrassing for someone to announce their privilege. But their discomfort seemed to me to be unable to accommodate my political desire to visibilise the distorted nature of our lived experience on account of the privileges one either enjoyed or didn’t, depending on whether one’s identity was framed by being either coloniser or colonised. For the first world to admit they remain first world would mean to acknowledge that their wealth and status have been the consequence of colonialism.

I’ve always maintained ‘third world’ as part of my biography because I am invested in perpetuating the legacy of feminists of colour whose advocacy disrupted the whiteness of second-wave feminism. To say ‘third world feminism’ is to situate political ideology beyond the Anglo-Saxon world and to recognise the immense contributions of feminists of colour who come from previously colonised or colonised spaces or even the margins of political discourse. To me, the term has always felt not only legitimate but validating and visibilising. When I encountered the curators’ reluctance, I suddenly began to doubt myself. I wondered if I had missed a memo about the term being retired and momentarily forgot that they were functioning like white feminists, oblivious to the wealth of feminist discourse across the spectrum of colour and queerness. Their intentions were not dubious in any way. They were just ignorant of the legacy I have been coding my practice within.

Nonetheless, I did a quick search online to re-examine whether I needed to update my definition of the term. I came across an abstract of a paper by Ipshita Chanda that echoed my intuition about what the term encompasses: ‘The ‘Third World’ is defined in relation to colonialism and postcolonial world systems, keeping in view the common bases of gendered exploitation and oppression as well as the specificities of diverse histories, pre-colonial structures, and colonial policies.’ Another description on the Amherst College website resonated with me: Third World feminism posits that women’s activisms in the Third World do not originate from the ideologies of the First World and specifically centres Third World women’s radicalism in their local/national contexts and struggles.

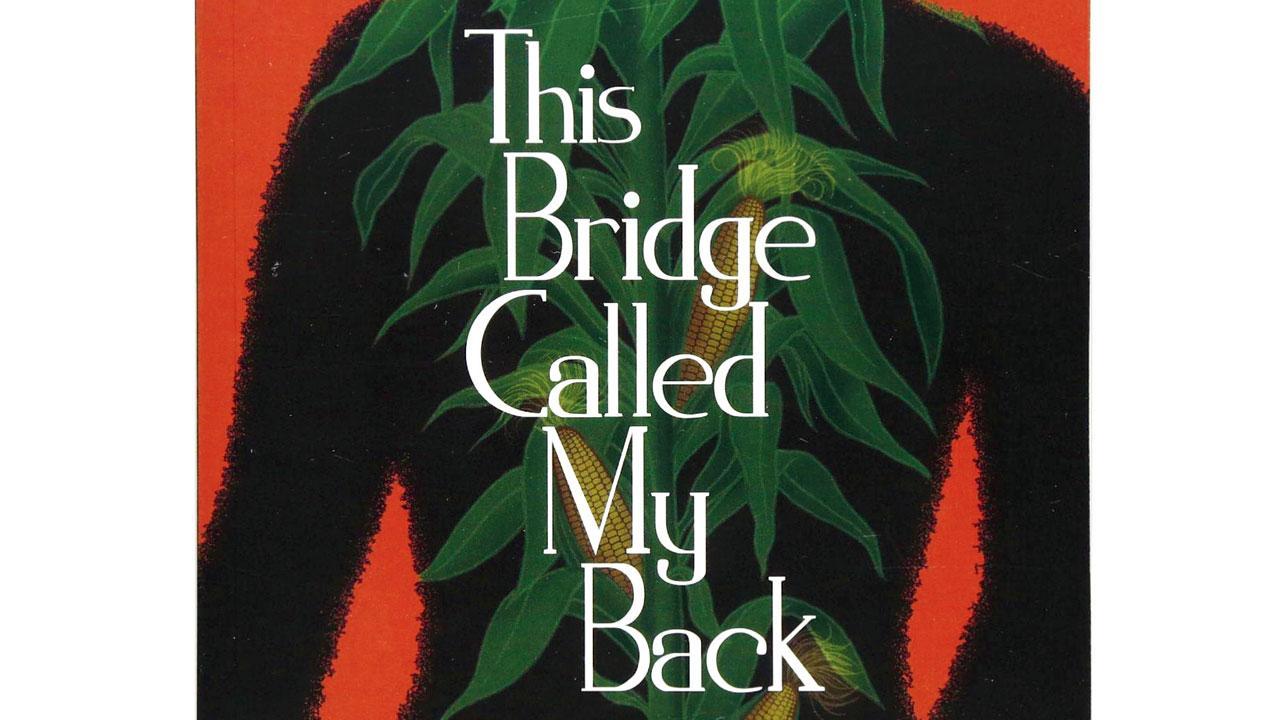

At the time I was so absorbed between childcare, full-time work commitments, recovering from COVID and trying to be functional that I couldn’t find in me the energy to challenge their reservations. I would have liked to have referred them to the historic anthology This Bridge Called My Back that celebrates this position, and particularly to Gloria Anzaldua’s Speaking in Tongues: A Letter to 3rd World Women Writers, which for sure must have been translated into multiple languages. Instead, I tried to negotiate. I first proposed ‘feminist of colour’ but felt dissatisfied with the term because it didn’t sufficiently pin down my recent immigrant status. I wanted it to be known that I come from a different context. Finally, the curator proposed ‘feminist from India’. I agreed to this compromise, too weak-willed from COVID.

Since then, I’ve been thinking about what it means to be offered a platform but to have someone still dictate the parameters of your identity. It is a form of discursive violence, too familiar to third world feminists like me.

Deliberating on the life and times of Everywoman, Rosalyn D’Mello is a reputable art critic and the author of A Handbook For My Lover. She tweets @RosaParx

Send your feedback to [email protected]

The views expressed in this column are the individual’s and don’t represent those of the paper.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!