Having a child shouldn’t have to depend on whether one can afford expensive in vitro fertilisation. Soon it won’t, with BMC hospitals set to roll out subsidised or free treatments for all. But is the city’s health infra ready for it?

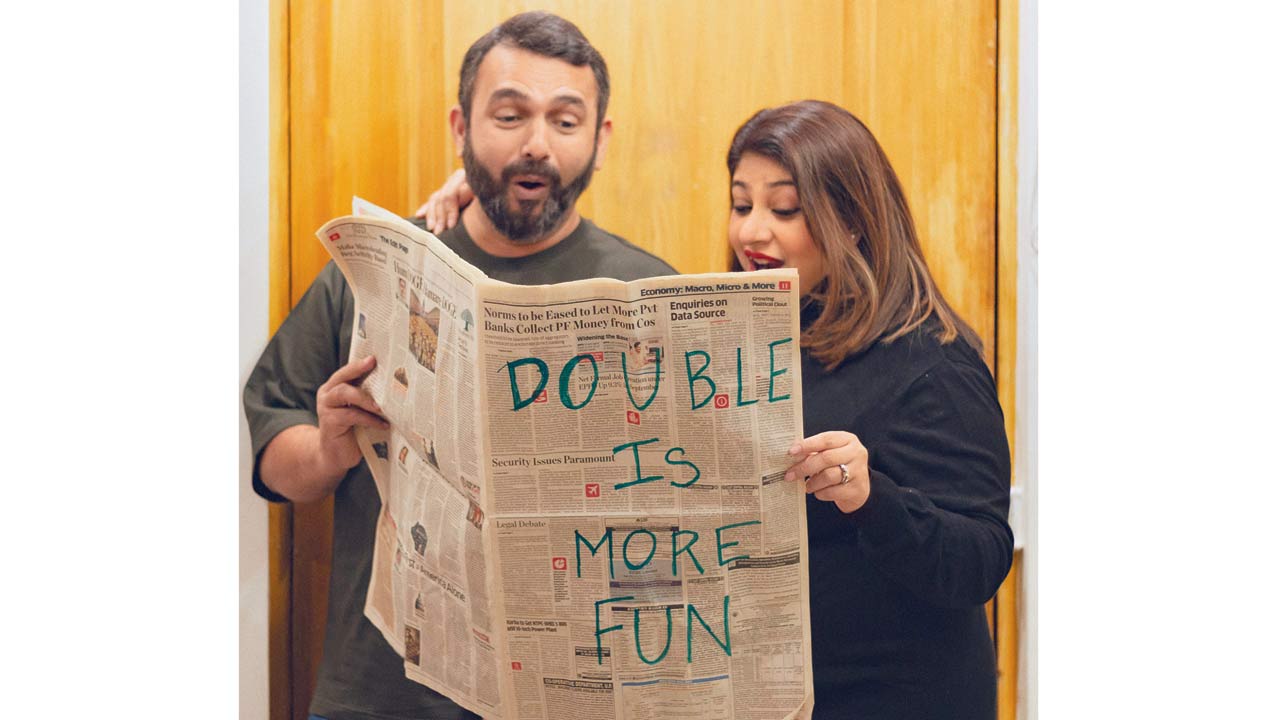

Aarti Mehra and husband, Sanjay, with their twin girls conceived via IVF. Pic/Kirti Surve Parade

Pineapples confused Aarti Mehra. Why is this fruit hailed as symbol of fertility on the Internet but Mehra was specifically told to avoid it when she started her in vitro fertilisation (IVF) treatment? In contrast, women on online infertility communities recommend consuming the fruit before their fertility doctor’s appointments to improve chances of conception, and some even wear pineapple motifs as good luck charms.

ADVERTISEMENT

Whichever advice she ended up following, the Goregaon resident is a rare success story, having conceived her twins after the very first round of IVF. “I know I am one of the lucky women. I have so many friends for whom the struggle to conceive is still on,” says Mehra.

She got lucky on another aspect—just that one round of IVF alone would have cost Mehra anywhere between R4 and R8 lakh, but as an advisor at an US bank, luckily her work insurance scheme covered the cost.

Smriti Notani

Smriti Notani

For most others, IVF can be a long, painful and expensive process. But Mumbaikars can take heart that at least one of those things is set to change—the BMC on February 4 announced a huge investment push for IVF centres at three of its hospitals to make fertility treatment more affordable for all classes. Out of a total health infrastructure budget of R7,380.44 crore, the civic body allocated Rs 2,455.89 crore to King Edward Memorial (KEM) Hospital in Parel, BYL Nair Charitable Hospital in Mumbai Central, and Lokmanya Tilak Municipal General Hospital in Sion (aka Sion hospital) to expand their health services, including IVF.

This is a sizeable investment by the civic body, accounting for over 33 per cent of its health budget, but it remains unclear how much of the outlay will go towards IVF. Amid unprecedented infertility rates, IVF centres mushrooming overnight, and the sheer number of desperate couples who are trying to conceive, the BMC’s move feels like the first step to acknowledging growing infertility among city’s residents—men and women. It’s also anticipated to destigmatise IVF and conversations around infertility among economically weak sections.

The National Family Health Survey 2019-21 (NFHS) documented a fall in the national total fertility rate (TFR) to 2.0, or two children per woman. In urban areas, this number is even lower—1.6. While these statistics might sound like a women’s fertility issue, it’s important to note that they also include increasing infertility among men—a problem that remains taboo in India.

Goregaon resident Aarti Mehra struggled getting pregnant through IVF treatment. Pic/Kirti Surve Parade

Goregaon resident Aarti Mehra struggled getting pregnant through IVF treatment. Pic/Kirti Surve Parade

In 2024, ResearchAndMarkets.com released a 70-page report on the Indian IVF industry, value it at $1.6 billion or Rs 14,000 crore in 2023. The report forecasted that this figure would grow to $1.82 billion or Rs 15,000 crore by 2030. It makes sense then that both global and national healthcare chains want a slice of the pie.

At eight months of pregnancy, Smriti Notani admits she is “ready to pop” as she speaks to us over the phone. Due for delivery next month, Notani is grateful that IVF worked out for her in the first round, but her treatment was not covered by her employer-provided insurance policy.

“I was lucky that it was successful in the first go. So many women go through multiple rounds, which leaves them drained—not just emotionally and physically, but also financially,” says Notani, a Khar resident.

Apart from the lakhs spent on each IVF cycle, most fertility clinics also charge a lump sum of R80,000 annually to store the patient’s eggs or embryos. This is hardly the kind of money that most working class families can afford. But the BMC’s push to make IVF more affordable could now make the dream of having a child possible for many such couples.

While Sion currently already offers free fertility assistance to underprivileged couples, the eventual goal is to also offer subsidised IVF treatment for R25,000 to R30,000 per cycle, with KEM Hospital serving as a model for other hospitals to follow. One cycle takes about two to three months, from medical tests and hormonal injections to transferring the fertilised embryos into the uterus.

“Fertility treatment consists of two primary procedures: IUI (intrauterine insemination) and IVF. When couples visit us, we first assess the underlying issue, whether it lies with the woman or the man, and proceed with the appropriate treatment accordingly,” says Dr Mohan Joshi, dean of Sion Hospital.

Smriti Notani is due to deliver her twins in March

Smriti Notani is due to deliver her twins in March

“We initially explore natural methods to facilitate pregnancy before moving to medical interventions. The first step is IUI, which a relatively less invasive procedure. If IUI fails, we conduct further studies and, if necessary, opt for IVF. IVF is a more complex process involving egg retrieval, fertilisation in a laboratory, and embryo transfer,” he adds.

Discussing the financial aspect of IVF treatment, Dr Joshi says, “In private hospitals, IVF treatment costs several lakhs per cycle, which can go even higher at high-end hospitals. However, at Sion Hospital, we provide this treatment completely free of cost. Offering IVF services in civic-run hospitals will greatly benefit couples, particularly those from lower-income groups.”

It’s free, but will it be effective? BMC hospitals are often resource-challenged, but Sion hospital has been making waves with its IVF success rate having more than tripled since its IVF centre’s launch last year. “Our success rate has significantly improved, increasing from 23 successful cases initially, to approximately 70-80 now,” Joshi says with pride.

KEM hospital will provide mandatory counselling to couples who visit for fertility treatment

KEM hospital will provide mandatory counselling to couples who visit for fertility treatment

Over at KEM Hospital, the IVF centre is in its initial phase. The hospital currently offers counselling services and an outpatient department (OPD), while civil work for the next phase is underway.

Dr Sangeeta Rawat, Dean of KEM Hospital and GS Medical College, confirmed that all logistical preparations are in place for phase two, including the availability of an embryologist. “The treatment will be provided based on a financial assessment by our medical social workers. Depending on the couple’s economic condition, treatment will be either subsidised, or completely free in genuine cases,” she explains.

However, despite excitement bubbling among both patients and the hospital management, government action seems to be slow. Both KEM and Sion hospitals are yet to receive phase one approval from the government despite applying six months ago, reveals Dr Sangeeta Rawat.

Anjali Jha With Son Ivaan, And Husband, Kumar Shekhar

Anjali Jha With Son Ivaan, And Husband, Kumar Shekhar

Dr Niranjan Maydeo, Head of the Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department at KEM, noted that while the plan has been commissioned and inspected, state government approval is still pending. Meanwhile, preparations for the second phase, including laboratory and operation theatre setup, are ongoing.

KEM’s IVF centre has been funded by infertility expert-turned-angel investor Dr Aniruddh Malpani, under whose initiative the first 100 IVF cycles at the clinic will be provided free of cost on a first-come-first-serve basis. “As the centre expands, we will explore ways to sustain and grow the initiative,” adds Dr Maydeo.

While the hopes of countless couples ride on the BMC’s IVF programme, it remains to be seen how effective it really is on the ground. But we can look to a similar scheme in Delhi for an indication of potential problems.

When freelance journalist Anjali Jha moved from Mumbai to the national capital seven years ago, she explored the Delhi government’s fertility treatment options but found them wanting. “After one very painful miscarriage and no success in natural conception, I went to a goverment hospital to get some initial tests done. Since my husband is a central government employee, we knew our treatment would be subsidised and extremely affordable. But I did not go ahead with my IVF there because we realised that there were too many patients waiting for treatment, and there was a huge delay in getting appointments,” she recalls.

“In December 2022, my husband was asked to get some tests done, but when we tried to schedule an appointment, the only slot available was in February 2023,” she tells us. One can only imagine how many more months it would take to jump the rest of the hoops before their IVF procedure could even begin.

They switched to a private centre and “by February, I was already mid-IVF”, says Jha, adding that she skipped IUI treatment altogether because she considered it “a waste of time and money”, apart from also being “brutal on the body”. Not all women have the same kind of health literacy or financial power to make a similar decision though.

“At the government hospital, I realised women from economically weaker sections had been doing IUI for two years or more. They were either not aware or being told to move forward to IVF. It was heartbreaking to watch these women go month after month to get the IUI treatment,” she adds.

Jha also observes that there was little to no counselling provided to the women, who were often accompanied by their mothers-in-law. This is a worrying gap that Mumbai’s administration would do well to prevent, especially when it comes to a sensitive topic such as infertility issues.

Goregaon-resident Mehra recalls how, while she was undergoing multiple rounds of IUI in early 2021, she felt shame for her body “not doing the most natural thing it was supposed to do—conceive”.In 2022, she switched to IVF and went on to conceive and deliver her twin daughters in December that year.

“You have to go through a lot of fertility tests that involve poking and prodding in your vagina. It is very difficult physically and emotionally. Your mind is filled with anxious thoughts like ‘What if I can’t conceive because there’s something wrong with me’,” Mehra recalls.

She faced another mental health crisis when halfway through the course of hormone injections, she suffered a dog bite and had to take the anti-rabies vaccine. “It was a freak accident. Since I was more than halfway through the hormone injections I decided that I would take both injections [hormone and anti-rabies] but couldn’t take anything for the pain because it would have risked my IVF treatment. But no one tells you it gets this difficult,” adds Mehra.

A freelance content writer Notani, has always been a big proponent of therapy, but it took on even greater significance during her IVF therapy. “I was constantly in touch with my therapist. But I also understand that this is a privilege and I was lucky to have it. I do think that this is a vital tool to have in your arsenal as well,” she says.

Fortunately, this is something our civic hospitals are prepared for. Couples that opt for IVF treatment at KEM will also be provided pre-treatment counselling at the hospital’s psychiatry department, says Dr Maydeo, adding, “It is crucial for patients to understand that IVF does not guarantee success, and counselling helps them prepare for potential challenges.”

At Sion hospital, counselling and mental health support will be provided throughout treatment, all the way until the child’s birth, says Dr Joshi.

There are plenty of issues to iron out, and it remains to be seen how the BMC will tackle infertility stigma among the economically weaker sections, as well as handle the huge caseload that is expected once the scheme is formally launched. But for now, we have hope.

Mehra, on learning about BMC’s IVF initiative, says, “My domestic worker’s daughter has been having problems conceiving. I will tell her to go and enquire at BMC hospitals. I think everyone who wants a baby should have a fair chance to have one, no matter what their financial standing might be. This is really good news…”

Rs 4-8 lakh

Cost of each IVF round at private centres

Rs 80K

Annual charge for pvt storage of eggs or embryos

Rs 0-35K

Promised cost of each round at BMC hospitals

More agency for women

For some, IVF can serve as a sure-shot way to time their pregnancy to fit the timeline they want, giving women more agency over their bodies. Swati Babel, 38, a financial analyst, opted for IVF after during the pandemic, when she was working from home in Navi Mumbai.

“I had no pressure to have kids and both my husband and I had no fertility issues, but we knew we had only until the pandemic ended for me to have a child and be able to take care of them, since we were all working from home,” she tells us over the phone from Dubai, where she has since moved. Babel’s strategy worked, and she delivered twin girls in 2022.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!