A fascinating book produced by the Godrej Archives tells you how the chairs that India’s working population sat and worked on have evolved since 1930. P16

The Ayama chair is a modern interpretation of the charukassela, created from a collaboration between Pascal Hien and Nikita Bhate of SAR Studio. It references the unique joinery details of Sankheda chairs from Gujarat, and other Indian reclining chairs that are often low, wide, with a sling seat to adapt to various body types. Pic Courtesy/From the Frugal to the Ornate/Godrej Archives

The chair is so ubiquitous—you don’t even realise when you are sitting on one. You are using the chair unconsciously, and don’t pay attention to it—unless you are buying one, of course,” says Vrunda Pathare, head of Godrej Archives. Perhaps that’s the reason why Pathare and her team have decided to publish a whole book about the indispensible piece of furniture. From the Frugal to the Ornate is written by graphic artist and designer Sarita Sundar.

ADVERTISEMENT

“In 2009, when the typewriter factory was shutting down, we had decided to celebrate that object, which has a public recall. It was a people-centric object. Object histories are not undertaken in India; and as an archive, we want to cover different kinds of histories to raise awareness. We were already contemplating another object to explore after the typewriter and coincidentally, when Sarita mentioned her research on chair in 2017, we were like ‘Why not?’,” says Pathare.

She’s right.

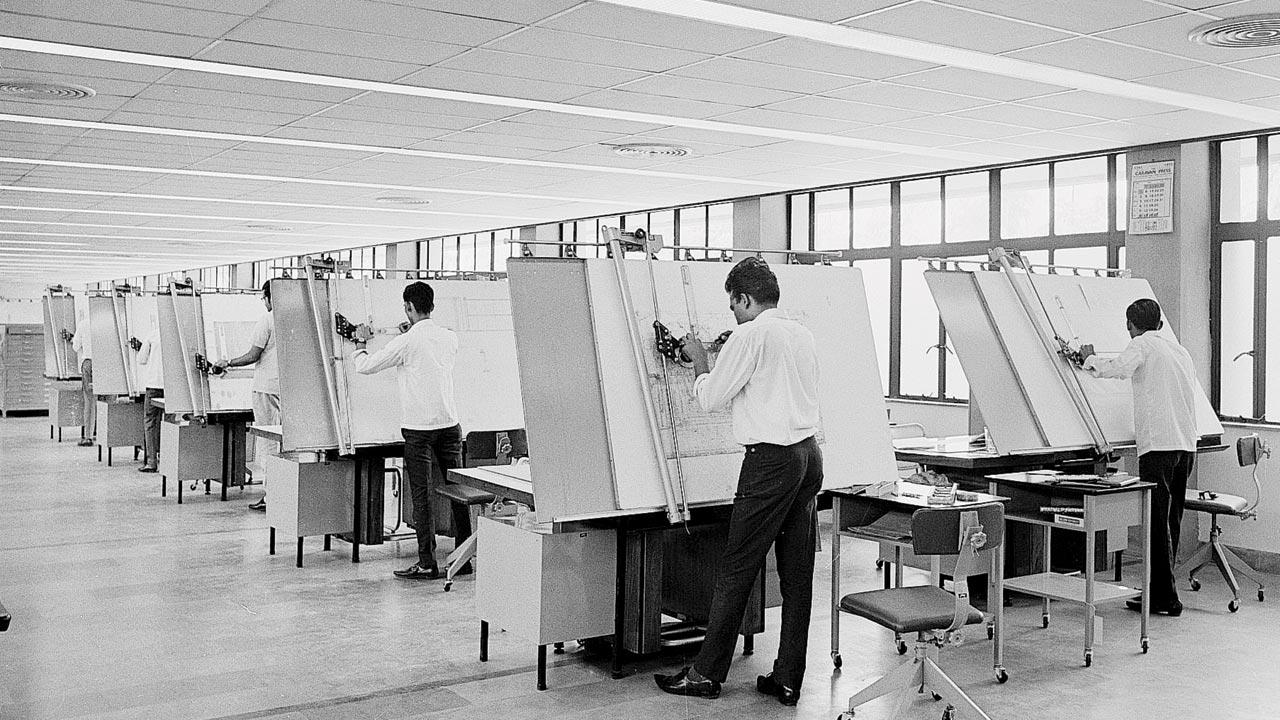

The CH-2A was a popular chair among typists and draftsmen in the 1960s and 1970s. Photographed at the Godrej Learning Centre, c. 1970

The humble chair could be the piece of furniture that occupies the least space in our head. Maybe at least until you reach middle age, and your lower back starts screaming for proper support. Godrej began that journey in 1930, when the conversation of modernity began.

“We started locks in 1897, safes in 1902, the every-home-has-one steel almirah in 1923 (which turns 100 next year), and the chair in 1930s,” says Pathare, adding, “We wanted to contextualise Godrej in the wider narrative. We look at history of Indian subcontinent through the lens of this object; at concepts like how the chair is relevant socially as well. The seat has hierarchies: Who will sit on it? Where is it placed? etc. It also gives us the opportunity to see what Godrej did with chairs.”

Sundar, the author, adds to Pathare’s view saying chairs cater to our needs, but also assign behaviours—of authority, submission, power, surrender, privilege, resignation, decorum, propriety, docility, endurance, comfort, and often, discomfort.

In 1939, the Godrej CH-8 Chair and metal desk featured in a newspaper article, and was referred to as the “ideal typist-receptionist” chair for offices. By 1939,

the company was promoting the idea of an ideal work space furnished with steel designs that were economical, space-saving, and durable. The Godrej CH-4 Chair and its variants, in particular, were a pioneering innovation.

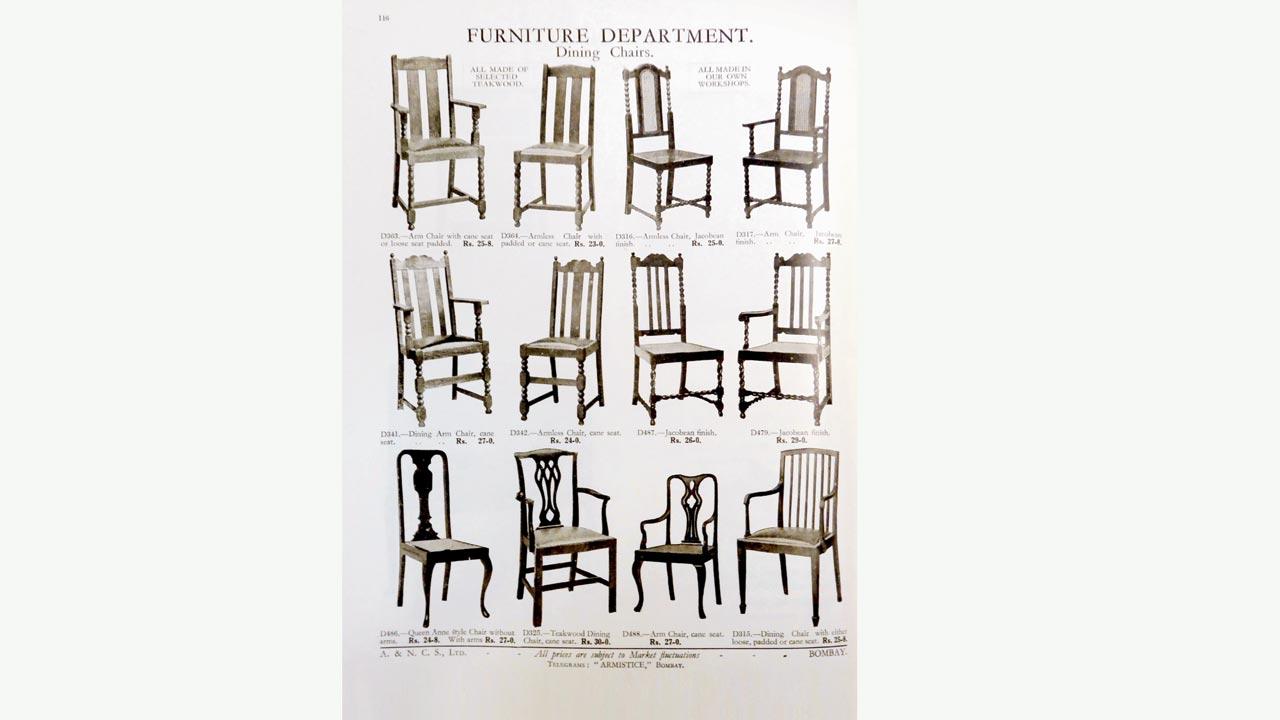

Army and Navy Stores, one of Bombay’s largest department stores in the late colonial period, offered customers dining chairs in a range of styles. This page from the 1933 catalogue illustrated some of the choices (Queen Anne, Jacobean, etc), seating materials (cane, added, loose cushions), and the option to add arms. Pics Courtesy/From The Frugal To The Ornate

“The cantilevered, stainless steel frames, when most chairs had four legs and were made of wood, transformed old offices with heavy wooden furniture into modern spaces,” says Sundar. “With its woven seat and backrest, it was hailed as being perfect for mass production. In all likelihood, it was inspired by the 1925 Wassily Chair and the 1928 Thonet Cesca Chair by the Bauhaus designer Marcel Breuer.”

Pathare and Sundar both credit the Art Deco movement and the office culture that became a part of working India’s life post the 1940s, an important factor for the evolution of the chair.

“NID [National Institute of Design] came up with their designs, and then there were the Chandigarh Chairs—everyone was figuring out their modern take on it. It was a massy product—government offices and banks, all offices needed it. And since it was made of steel, it could be made and used anywhere,” explains Pathare.

Vrunda Pathare and Sarita Sunder

Sundar informs that in the pre- and post-colonial periods, classical English, Dutch, and Portuguese styles influenced the structure. Distinct traces of applied ornamentation with Indian influences—often inspired by Mughal or Hindu architecture—or the Indo-Saracenic style, set these pieces apart from their European counterparts.

“So the frames and the joinery details came from European designs, while surface ornamentation and form followed Indian influences. A Chippendale-style chair made in India could incorporate the typical ball-and-claw foot, with a gentle curve of a Queen Anne’s, style or a Gajasimha’s trunk would be used to create that curve—you’ll see this in some blackwood pieces. At the same time, an acanthus leaf motif would blend into a makara’s jaw on the chair frame or leg. During the mid 20th Century, there were Art Deco influences, and later the Bauhausian aesthetic as simpler forms and mass production techniques transformed chairs into a modernist idiom,” she says.

The point of the book, in the end, for Pathare is that Indians learn how to look at an object through different perspectives; and through the object, look at history in different ways. “Maybe it will inspire architects and designers, who want to give it a new spin,” she says.

For Sundar, the chair is not just a chair. “The seat—through history and across the globe—operates as an instrument of manipulation: To elevate people, to keep others in their place, to grant distinction, deny prerogative or a means to differentiate. The denial of a chair is social exclusion sanctioned in feudal societies, penalisation in prison cells, or deliberate austerity in yoga retreats. In the politics of prominence between men and women, young and old, master and servant, boss and employee, the seat assumes agency—and is no longer a chair meant for seating!”

Phew. Grab a chair.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!