Body positive, provocative, sexually unapologetic and brutally honest—four women we follow and admire talk to us ahead of Valentine’s Day about why their life’s work is dedicated to inspiring the ladies to reclaim azaadi in life and bed

Artwork/Priyanka Paul

‘I love the concept of love. It’s the only thing worth living for’

ADVERTISEMENT

Priyanka Paul

Illustrator and activist

Priyanka Paul can’t remember ever shying away from discussing sexuality. Not as a 17-year-old, when she first began drawing women and their bodies, or as the 24-year-old she is now who has spoken about everything from #MeToo to menstruation, body positivity and sex education—she wrote a sex guide at the age of 20. “I was raised by a vocal, feminist mother, and she normalised it all for me,” Paul tells us. Having been sexually violated while in her early teens, made her want to question and challenge systems that had reduced women’s worth to sexual objects.

Like gender constructs, Priyanka Paul challenges fashion trends, projecting herself with stark honesty on her Instagram page. Pic/Pradeep Dhivar

Like gender constructs, Priyanka Paul challenges fashion trends, projecting herself with stark honesty on her Instagram page. Pic/Pradeep Dhivar

Navi Mumbai-based Paul, who is a mass media graduate from St Xavier’s College, cannot be pigeon-holed into a box—one day, she sports blonde hair, another day it’s Barbie pink or peacock blue. Of late, it’s plain jet black.

One of the first set of paintings Paul brought to life was called the Goddess series, which re-imagines five goddesses from different cultures as modern women, and how they would exist on social media. “It was based on a poem by Harnidh Kaur called Pantheon,” she recalls, adding, “While it sent out this message of collective liberation, it got mad hate in India because I had drawn Goddess Kali.”

Paul describes gender as a construct. “We need to abolish gender. If it were broken, we all would be so much freer,” she feels. “Playing into these stereotypes, leads us to belittling ourselves further. We need to learn to enjoy the full spectrum of human emotions and experiences,” says Paul, who identifies as non-binary (non-binary persons may identify with more than one gender, no gender, or have a fluctuating gender identity).

Priyanka Paul’s provocative art is synonymous with strong lines. This sketch re-imagines five goddesses from different cultures as modern women, and how they would exist on social media

Priyanka Paul’s provocative art is synonymous with strong lines. This sketch re-imagines five goddesses from different cultures as modern women, and how they would exist on social media

She sketches women, because “I love them”. “I may not identify as one, but I grew up as one. For me, not identifying as a woman simply comes from the space of wanting to break the construct. If I can be myself, without being gendered, I would be happy.”

According to her, desire cannot be gendered. “The problem is that women’s desires have been curtailed for centuries, because desire symbolises female autonomy... it is power and we need to reclaim it.”

Like anyone else, Paul loves the idea of love. “I am actually making a Valentine’s Day card as an art piece, and if you open the card, it will read, ‘Valentine’s Day is a romantic, capitalist scam, but for you, I’d be scammed any day,’” she says, breaking into giggles. “I love the concept of love. It’s the only thing worth living for. I am generally hopeful, because there is nothing else left to believe in. So, I am putting all my coins there.”

Paul says she is going to keep talking about sexuality and desire through her art. “My work has always been an experiment in how honest I can be... social media is a difficult space to showcase this, because it’s really hard to be vulnerable to strangers. But it’s selfish to believe that it is not going anywhere and that

nobody cares.”

‘All our gods had consorts and our civilisation has always been about vilaas and pleasure’

Dr Alka Pande

Academic, historian, museum curator and author

Two years ago, when we first got acquainted with Delhi-based Dr Alka Pande, she had just released her book, Pha(bu)llus: A Cultural History, which was a one-of-its-kind exploration of ideas and beliefs around the phallus. We recall then, Pande revisiting a legend around Lord Shiva: Angered by the Devas, Shiva throws his lingam in the Deodhar forest, burning everything around. Brahma tells the devas and rishis to worship Uma (Parvati) because only she can make Shiva’s organ quiet. This story reminded us why the feminine force is the more controlling and dominant energy. Yet, this is not the knowledge most Indian women have grow up with.

Alka Pande standing in front of a painting titled Aalingan by Anni Kumari, which shows an allegorical intimate embrace at the ongoing India Art Fair in New Delhi. Pic/Nishad Alam

Alka Pande standing in front of a painting titled Aalingan by Anni Kumari, which shows an allegorical intimate embrace at the ongoing India Art Fair in New Delhi. Pic/Nishad Alam

Sixty six-year-old Pande admits that her own traditional upbringing impeded her understanding of sexuality and desire. “My generation of women were taught to sublimate sexuality instead of celebrating it... virginity was a big deal, and feeling desire was seen as gandi baat. But this is a natural human emotion. Women have been repressed far too long.”

Pande began acknowledging this experience, only when she pursued a doctorate degree in England in the late 1990s. “It was on the theme of Shiva and shakti called Ardhanarishvara [the composite male-female figure of the Lord Shiva together with Parvati]. The issue of gender, gayness and homosexuality were simultaneously coming up in a big way in the college where I was studying [Goldsmiths, University of London], and all of this became part of my research. I later converted the art historical document into a cultural book called Ardhanarishvara the Androgyne: Probing the Gender Within.”

Six years later, she was approached to do a book on Indian erotica. “I jumped into the idea without any knowledge about the world that was going to open up to me.” For starters, she remembers it being a tough book to do, because “how do I draw the line between pornography and the aesthetic of erotic?”. “There is a thin line,” she says. “I went back to my doctoral work, and looked at the concept of rasa and shringhar, and I realised how all our gods had consorts, and how our civilisation itself has always been about vilaas [enjoyment] and pleasure. I became acquainted with a lot of Sanskrit erotic poetry as well, which was quite a revelation.”

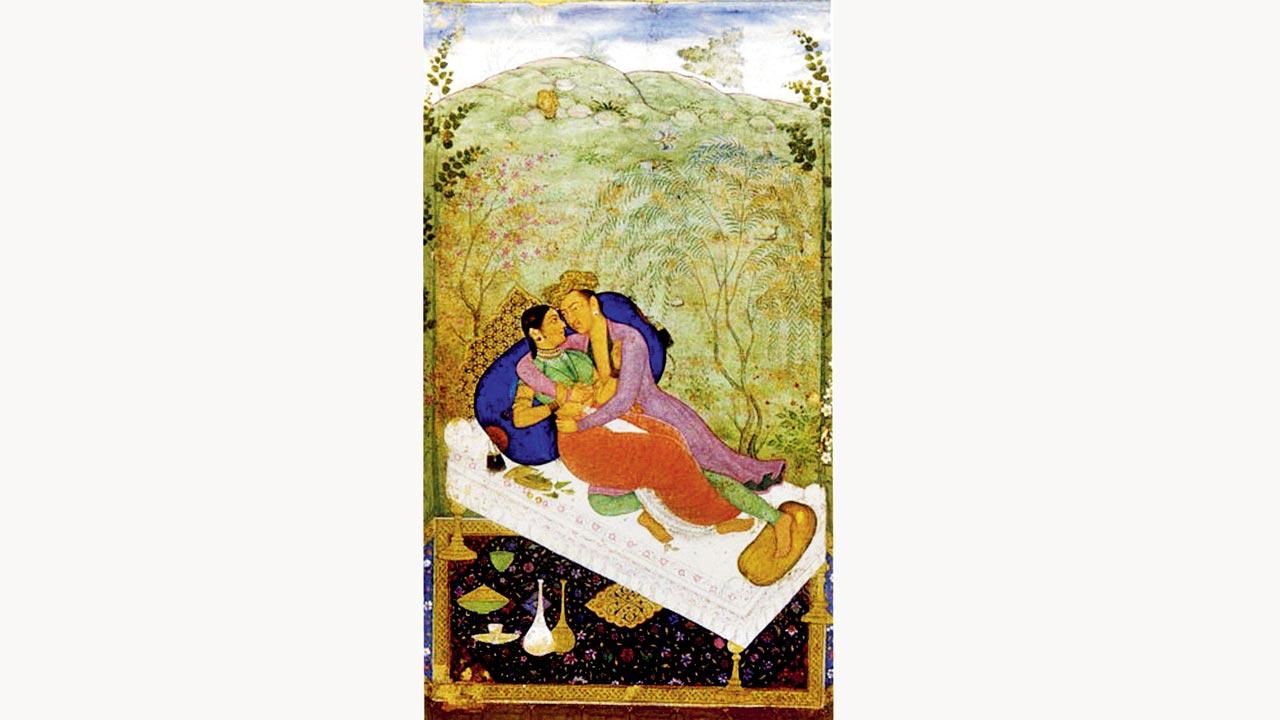

A painting of Prince Murad, son of Akbar, with his wife Mirza in a garden. Mughal School, 16th century, courtesy, Freer Gallery of Art. The painting was part of a 2022 book, Al Fresco Kama: Love Under The Open Sky, curated by Alka Pande for Speaking Tiger Books

A painting of Prince Murad, son of Akbar, with his wife Mirza in a garden. Mughal School, 16th century, courtesy, Freer Gallery of Art. The painting was part of a 2022 book, Al Fresco Kama: Love Under The Open Sky, curated by Alka Pande for Speaking Tiger Books

While the book helped her explore the lovemaking of Indian gods, and the erotic in Indian art, that work had the underpinnings of academia. “It was only in 2014, when I curated an art show on the spiritual and erotic in the Kamasutra, in Paris—by which time I had re-examined and re-read the Kamasutra in many different ways—that I found new insight into sexuality in the physical way, and not just through allegories and poetry.”

Pande says this process not only helped her reclaim the Kamasutra differently, it also allowed her to push the envelope each time she wrote a book or curated a show. By then, she was in her 50s, but the awareness of her sexuality, made her “fearless”. “The success I received because of my writings on desire and Kamasutra, gave me a different level of confidence. I didn’t have to prove anything to anyone, because I was so deeply invested in the subject. I understood how evolved our ancients were. It was the more Victorian prudery of the English that hemmed us in,” she argues.

Pande feels that with women becoming more economically empowered, they have started taking greater control of their bodies: “Our genders are fixed, sexuality isn’t. I think more women like to look at other women’s forms. Somehow, the feminine form is always beautiful... the curves, the beauty, I find it attractive.”

‘Self-determination is not just the right of nations and people, but of every individual’

Meena Kandasamy

Poet, writer, translator and activist

IF one had to browse through the titles that Meena Kandasamy’s near two-decade-long writing career has generated, her unapologetic resistance to casteism and patriarchy and its concomitant regressive core, would be evident. Her earliest poetry collections, Touch and Ms Militancy, bold and powerful as they were, breathed fire into her later works, The Gypsy Goddess (2014) and the more searing When I Hit You: Or, A Portrait of the Writer as a Young Wife (2017), which chronicled her protagonist’s abusive marriage.

Meena Kandasamy, known for the flamboyant sexuality in her poetry, says writers are capable of disrupting the system

Meena Kandasamy, known for the flamboyant sexuality in her poetry, says writers are capable of disrupting the system

On a weekday morning, in between handling her restive pet, Kandasamy tells mid-day over a telephone call from Puducherry that some of her earliest influences were poet Kamala Das and novelist Arundhati Roy.

“I see myself as someone following in the footsteps of these great, brilliant women who’ve walked before me.” There’s another name she adds to this carefully pruned list: Tiruvalluvar. A saint poet who, she says, is central to the lives of the Tamil people, but about whom no biographical details remain. Tiruvalluvar is credited with authoring the Tirukkural, composed somewhere in the first century BCE, and which remains one of the most vital texts of this ancient civilisation. Even over 2,000 years on, it continues to be a breathing and living entity. “Many Tamil children in school memorised the whole text or part of it... I started looking at it, and learning it by rote when I was a 16-year-old,” she says.

The 1,330 verses of the Tirukkural are divided into three sections: Morality, Materialism and Desire. Kandasamy’s just-published work, The Book of Desire, is a first-of-its-kind attempt to offer a feminist interventionist translation of the third section of Tirukkural. The erotic love poetry describes a hero’s encounter with a “deadly, intoxicating” Tamil woman. While she found it to be a “very democratic text” with more chapters dedicated to how the woman feels about her love interest, what bothered Kandaswamy, is that this “fear-inducing Tamil beauty, who holds court” in the poem, never existed outside of the book. And that’s because she was absent as a translator and commentator of the text. It was always the men. “For nearly 2,000 years, a woman had not touched [translated] the text. It really shows you the male nature of the Tamil intellectual landscape... women were never really allowed to share the same space. So, obviously, on the one hand, while the intellectual space is heavily based on caste-lines with only a certain class being seen as worthy of commenting on classical and ancient texts; it’s also very masculine, as there are no female scholars taking this up. There’s a lot of gate-keeping. As a woman, when I take up this place, [translating] as a classical scholar and intellectual, it is a disruptive act in itself,” says Kandasamy, explaining to us in simplest terms how feminism and agency work.

She remembers reading some of the earlier translations of the book, which were of course, by men, and being thrown off by the use of words like “union” and “congress” for sex. “So, how you take up this space is also important. And then change this space,” she says, “By putting women at the centre, and talking about desire and sex, when the author is actually talking about those things, without being shy about it—capturing the vibrancy, defiance, and vivaciousness [of the text], and what makes it so irresistible. In doing so, you are reclaiming the woman inside the book, instead of hiding her.”

That’s why she describes her translation as interventionist. “Sometimes, a book is not just a book; it’s a statement, it’s a political act... one that changes minds.”

Kandasamy, whose activism has been the bedrock of her writing, admits that the current environment needs women to take control of their narratives. “We are now living in a society where lovers are being punished with death if they love outside their caste, women are told not to fall in love—much of the discourse is against love and it is coming from regressive, political forces. There is a lot of moral policing, repression and shaming. That’s not our culture.”

Writers, she says, are capable of disrupting such a system, and working against inequality. “You can speak about your desires; normalise divorce, friendship,

same-sex relationships, and sexuality. We are living at such an interesting time, and there’s so much we have to say—and it’s being said of course.”

Kandasamy says her newest translation is only an extension of her work, and “the very flamboyant sexuality in my poetry”. In 2012, she wrote about her own brief and violent marriage, which explained the urgency to address the issue in her later works. “Self-determination, right to choose for oneself, is not just the right of nations and people, but of every individual. This is why I think in a patriarchal, caste-controlled society like ours, women have to embrace the necessary defiance to make their own choices in order to take control of their bodies, their sexuality and desires.”

Longing for sex

Not wine but it is sex that gives sheer delight at thought and such pleasure at sight.

No, not even a little-millet pout—total non-sulking is essential when sexual desire overflows and stands as tall as a palmyra.

He does not care for me, he does just as he pleases; yet my eyes know no peace, not having seen my man.

Petulant, I went to pick a fight, dear girlfriend – but my heart forgot that, and ran after him for sex.

Like eyes that cannot see a kohl-liner while it defines them, I do not see my lover’s faults when he is in front of me.

When he is with me, I see no faults at all. When we are apart, I see nothing but faults.

Like those who dive, aware they will be dragged away, I learnt the futility of anger by fighting with my lover.

Like drink, that reduces the drunk to objects of ridicule, so does the chest of this charmer.

Softer than flowers is making love…Few obtain its elegance.

Her eyes held tears as she sulked—we hugged, trembling with desire;her haste surpassed mine.

‘Nudity isn’t wrong. Being fully clothed isn’t wrong’

Roshini Kumar

Photographer, activist and model

IT was Roshini Kumar’s battle with cancer at 14 years—Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Stage IV—that made her look at life through the lens of a camera. Having dealt with body image issues as a child, the camera became a tool to understand herself, her body and her struggles. That’s when her journey with body positivity began. “I remember as part of the final project at the photography school where I was studying [back in 2015], I decided to do a nude shoot of myself, where I showcased my insecurities and how they had decreased. It was meant to be a personal accomplishment, as much as it was an art piece,” remembers the 30-year-old Mumbai resident. “But, I also felt that I needed to put it out there, because if I still cared about what people thought of me, it meant that I had not reached my goal of being comfortable in my own skin.”

Mumbai-based Roshni Kumar practices body positivity activism through photography. Pic/M Fahim

Mumbai-based Roshni Kumar practices body positivity activism through photography. Pic/M Fahim

When she shared the photograph in the nude on her social media, she remembers being a bit worried. “Nobody was doing these things then. Much to my surprise, I received great reviews. So many wrote to me, saying that they felt seen. This motivated me to do more of it.” That’s how Kumar’s body positivity activism began.

Kumar says that patriarchy, capitalism and misogyny can be particularly hard on women and queer persons. “They are shamed for looking good, wearing clothes they want to, for feeling sexy, and experiencing pleasure. I’ve seen so many of my friends struggle with this.”

In 2018, she launched the “bare series” to tear down the bias and discrimination, and “see bodies as bodies”. “The second time I did the series, I invited my followers on social media to come and be part of it. I picked a random set of 30 people, whom I then shot at my home. I asked my subjects what about their body made them insecure, and I tried shooting that aspect to remind them that they actually looked good, and that there was nothing wrong with their physical selves. A lot of them went back feeling wholesome and full, they said, and that’s the purpose of my work—to change skewed perspectives and challenge beauty standards.”

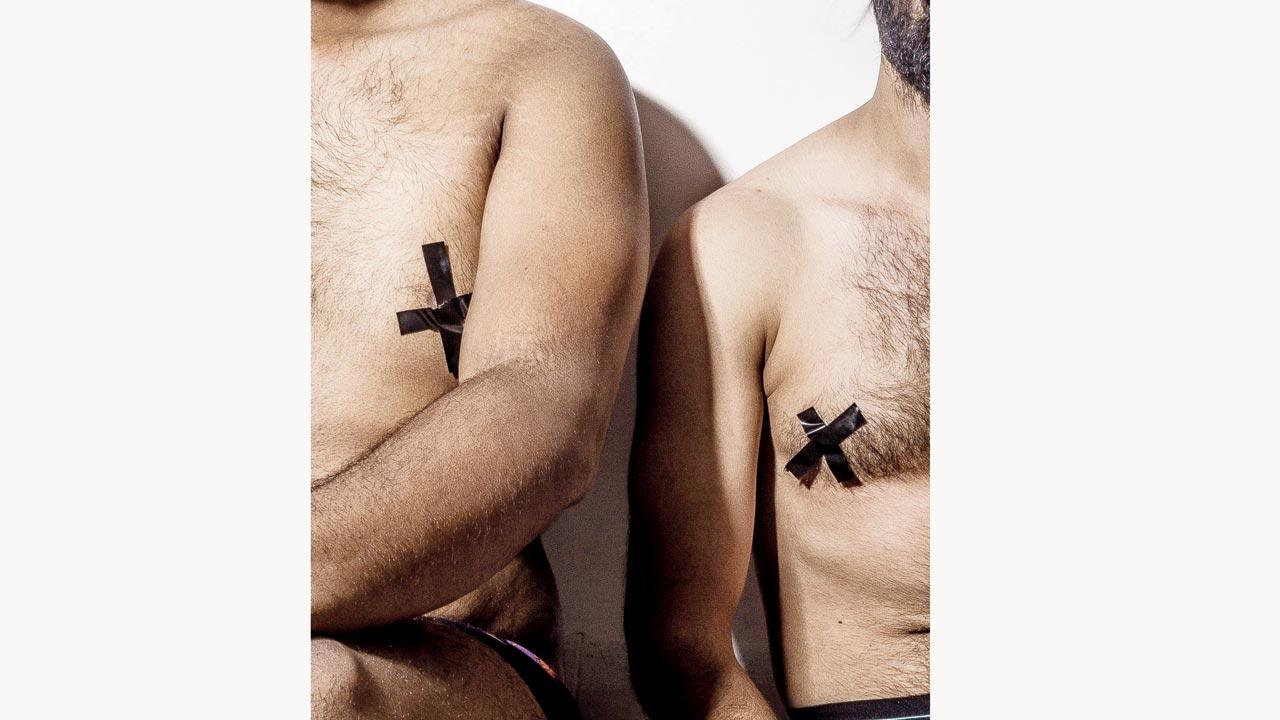

From Roshini Kumar’s series Bare, 2018. “I invited people from my social media followers who were ready to get vulnerable in front of the camera. These two lovely people came from different cities and let me photograph what they thought were their insecurities,” she says

From Roshini Kumar’s series Bare, 2018. “I invited people from my social media followers who were ready to get vulnerable in front of the camera. These two lovely people came from different cities and let me photograph what they thought were their insecurities,” she says

According to Kumar, body positivity and sexuality are inter-linked. “I identify as queer, but for a long time, I suppressed this, because society looks down at queerness as being different. When I started getting to know my body more and loving it more, I realised I had been hiding this side of me. That’s when I began shedding the inhibitions and exploring my sexuality.”

On her Instagram page, Kumar strips down to bare minimum—sometimes flaunting her curves in an animal-print bikini, or sitting comfortably at home in undies and sports bra. “Nudity isn’t wrong. Being fully clothed isn’t wrong,” she captions one of her posts. “I see people getting triggered every now and then by my posts. It doesn’t bother me, no. It only bothers me that they have been taught that this mindset is right. It shouldn’t bother anyone that someone is comfortable in their body enough to not care about standards... And constantly being sexualised because of ‘nudity’ isn’t even what I want. Y’all are projecting your own ideals onto this. I will happily sexualise myself when I wish to. I ain’t here to comfort you. I’m here to make you see perspectives you’ve never seen before,”

she writes.

Feeling pleasure, Kumar tells us now, helped her know what she wanted from herself and others, and the kind of energy she would allow into her life. “Desire and sexuality are so normal and natural that they don’t require a definition. It comes with just being; it’s as simple as nature. Until a few centuries ago, we celebrated sexuality. I remember researching for an article and learnt that the oldest known sex toy [32,000 years old] is older than the institution of religion and marriage. Colonisation messed us up, and it took our own culture away. We are still feeling the effects of it.”

Also Read: Valentine's Day 2023: Jay Shetty on fairytale romance, and what makes love last

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!