Who were the dynamic duo of collectors who contributed rare finds to the city’s only centre dedicated to Zoroastrian history and culture? We find out more at the re-opening of the FD Alpaiwalla Museum

Recreation of the “lifestyle room” of a wealthy Parsi merchant, with some artefacts belonging to the Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy family. Pic/Ashish Raje

Recent weeks have witnessed the city appreciate the rich socio-cultural and religious heritage of the Zoroastrians with a fine variety of celebrations. After celebrating the tricentenary of the sacred Bhikha Behram well at Churchgate, the community has reopened a beautifully designed, one of its kind centre—the FD Alpaiwalla Museum in Khareghat Colony on Hughes Road—Bombay’s sole showcase of Zoroastrian history. Set up and supported by the Bombay Parsi Punchayet (BPP), this archaeological and ethnographic museum has been the recipient of a generous grant from the Central government Ministry of Culture.

ADVERTISEMENT

A fair amount is known about the antique collector and bullion trader whose name the museum bears. Relatively less famous, however, is his erudite friend, the French-fluent scholar priest and archaeologist, Jamshed Maneck Unvala (1888-1961). Besides contributing vital finds from Susa and Yazd in Iran to this museum, he as importantly gave shape and substance to Alpaiwalla’s possessions.

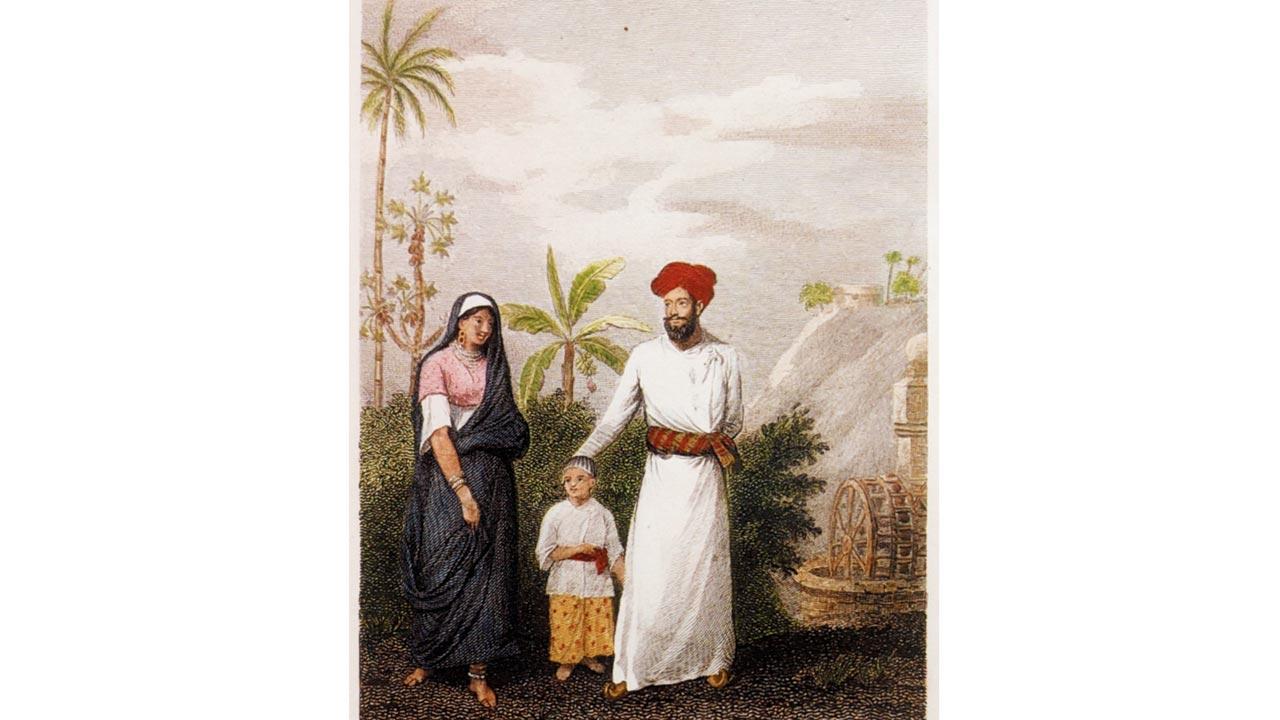

Parsees in Bombay, a celebrated engraving. Pic Courtesy/A private collection

Parsees in Bombay, a celebrated engraving. Pic Courtesy/A private collection

“Most collectors devote a percentage of their income to art collection. Alpaiwalla exercised no such self-restraint,” Nivedita Mehta, the museum’s first curator, had remarked. So completely consumed was Alpaiwalla by the passion for collecting, that the wide-ranging artefacts, arduously acquired over years, filled 11 overflowing rooms in his home. Including his bedroom. The merchant was compelled to sleep in his kitchen until the opportunity to donate the collection presented itself.

Eager to share his pieces with an appreciative public, Alpaiwalla began preparing detailed catalogues. The Khareghat Memorial Building with the Ranji Wing for the museum was built and the foundation stone laid in 1951.

Sadly, though, he died before the museum was inaugurated the following year.

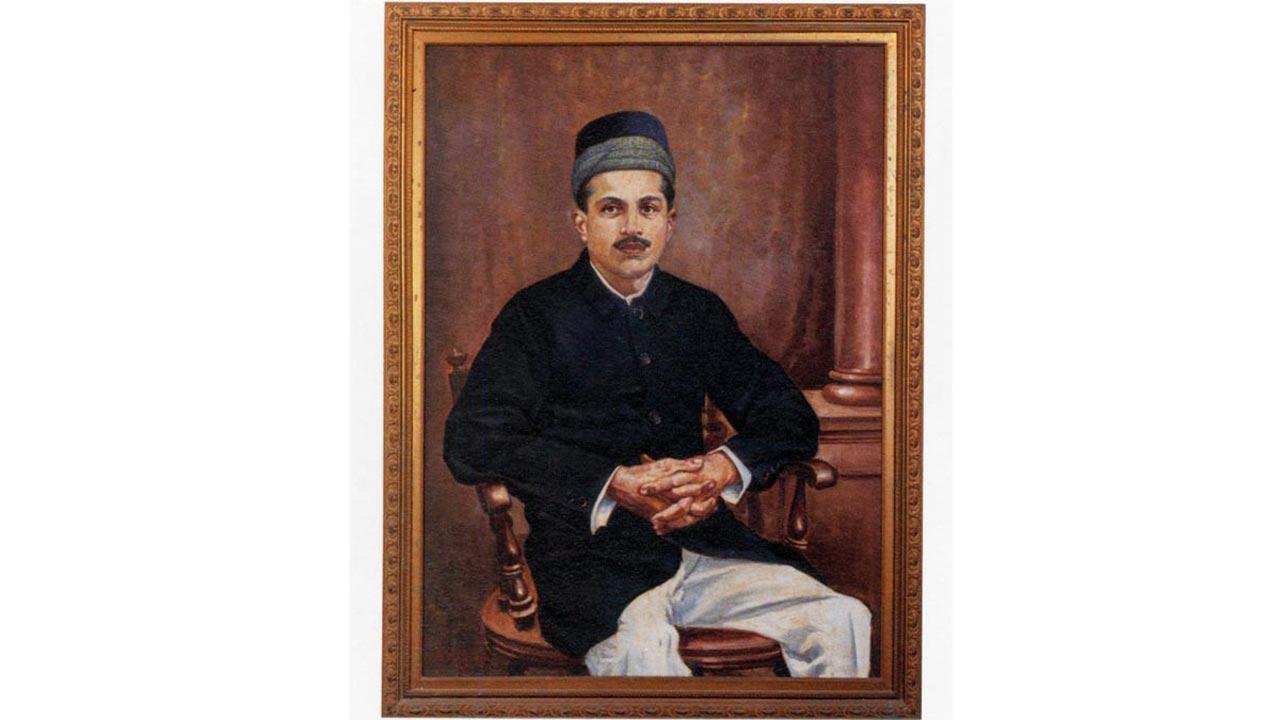

Framji Dadabhoy Alpaiwalla, founder of the museum. Pics courtesy/FD Alpaiwalla Museum

Framji Dadabhoy Alpaiwalla, founder of the museum. Pics courtesy/FD Alpaiwalla Museum

In stepped Unvala to realise Alpaiwalla’s dream, with the Bombay Parsi Punchayet (BPP) choosing him to curate and categorise the vast accumulation of items and organise them to be optimally displayed.

Describing the initial stage that bequeathed this enduring legacy, Cyrus Guzder, chief guest at the museum reopening, said, “When Alpaiwalla set up his museum, it was probably just a storehouse of this great clutter of items he collected. Unvala tried to bring order to the chaos. Now, many years after, the way we look at museums has changed in favour of objects made easily accessible, framed in a context and labelled for visitors to understand them.”

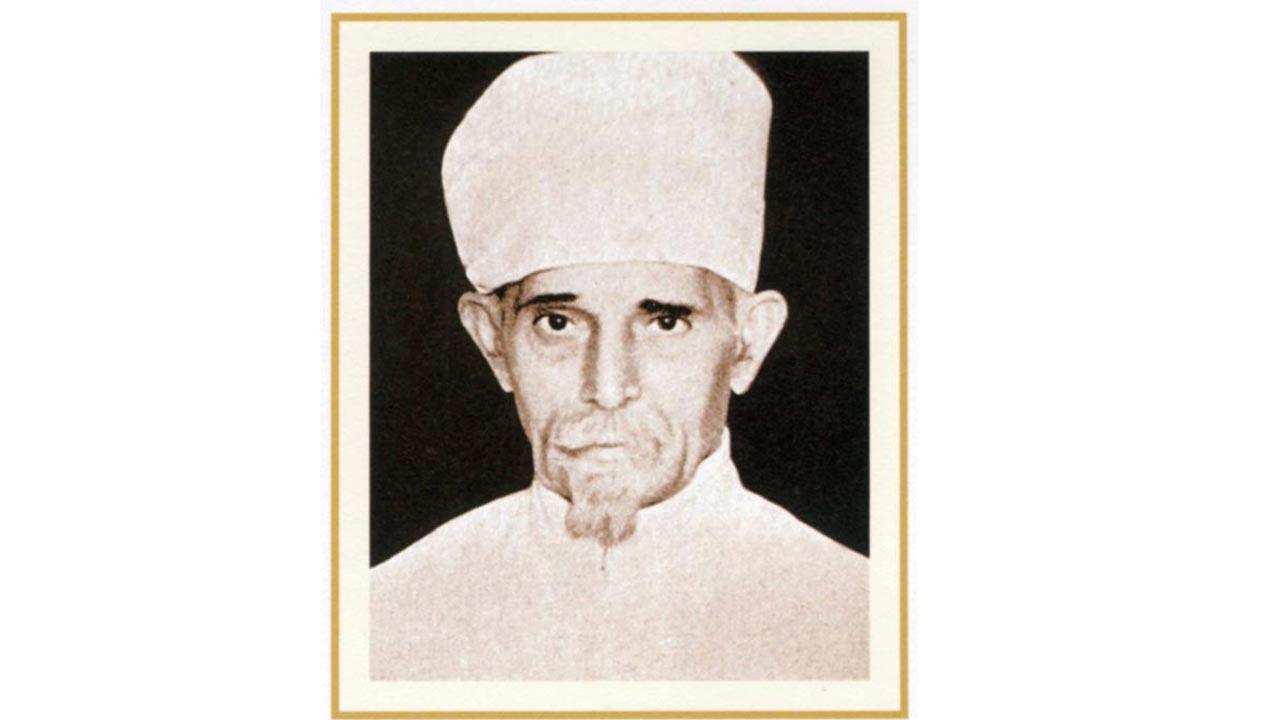

Jamshed Maneck Unvala, scholar-priest and archaeologist

Jamshed Maneck Unvala, scholar-priest and archaeologist

Piecing together a unique trajectory, defined by determination and discipline, Guzder pronounced Unvala an “intriguing” character. Born in a poor family in Navsari, while training to be a mobed who could perform priestly duties, Unvala developed great enough interest in the holy scriptures to wish to undergo further studies in Germany. A decision his penurious parents opposed but he took head-on at a difficult time—the start of World War I. Persevering, he stayed on till 1918, when he obtained his PhD from the University of Heidelberg, before leaving for Munich to lecture in Avesta Pahlavi and Sanskrit. From 1919 to 1921 he worked at Cambridge and Paris as a Government of India research scholar.

Unvala’s next stop was the SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies) in the UK, steeping himself in ancient Iranian and Indo-German philology. His keen grasp of languages, especially German and French, was soon to stand him in excellent stead.

On hearing that the French were conducting significant digs at the provincial town of Susa, he joined them. Artefacts from that very early site, dating approximately 4000 to 3800 BCE, are on display at the museum. Unvala’s knowledge of French enabling the translation of inscriptions, he collaborated with Roland de Mecquenem for 12 years, from 1927 to 1939. Returning to India, he was invited to helm the Department of Avesta Pahlavi in St Xavier’s College and prominent community institutions like the Sir JJ and Mulla Feroze Madressas, as well as the KR Cama Oriental Institute which he served as joint honorary secretary.

Earning a reputation for extraordinary learning and strong credentials in the fields of Persian and Zoroastrian archaeology, Unvala brought back from excavations marvellous examples of glazed bricks, Proto-Elamite tablets, toys and mother goddess figurines. The buff-coloured terracotta pottery from Susa, which was gifted to the Alpaiwalla Museum, forms part of Unvala’s collection.

Tracing his pioneering contributions in the Dr JM Unvala Memorial Volume, Dinshah Kapadia has written: “Laudable were his efforts for examination, from an archaeological point of view, the long forsaken dakhmas [Towers of Silence] at Tena [Surat in India] and Yezd [South Iran].” The tribute essay later notes: “He took an active part in the bi-annual All India Oriental Conferences and at nearly every session submitted a paper quite original, full of new information and ideas.”

The museum’s diverse exhibits span a sweeping timeline, stretching across eras from prehistory, to Susa and Persepolis, to other cities of the Achaemenid and Sasanian empires, right up to Zoroastrian life in 19th and 20th-century India. Occupying pride of place with an original 1618-issued firman (land grant) from Emperor Jahangir and the calling card of Dadabhai Naoroji when elected to the British House of Commons between 1892 and 1895, are 1900 books, rare manuscripts, carved furniture, embroidered textiles, coins, striking portraiture and porcelain. Along with the wonderful recreation of a Parsi merchant’s drawing room, with some artefacts from the Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy family, a must-see is the replica of the interiors of a fire temple. This model proves a welcome feature for non-Zoroastrian visitors curious to see the inside of an agiary.

“On the one hand, this passion for collecting represents the feeling of wanting to hold on to vanishing values. On the other, to give something that has value and is permanent,” added Guzder, “A museum basically has as its language its objects. But objects in and of themselves are dead. The challenge is to bring them to life, make each tell a story. Objects have many lives. They should immediately speak to an audience, narrating accounts about themselves or the context from which they come. This is how—exquisitely crammed in so short a space—Pheroza Godrej and Firoza Punthakey Mistree have reimagined the Alpaiwalla Museum for us. Between them and the BPP, the city is gifted a real treasure house of the history of our community.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!