A Pakistani couple whose recent exhibition documents Indo-Pak’s shared pre-partition heritage, makes sense of the invisible fault lines that separate the countries

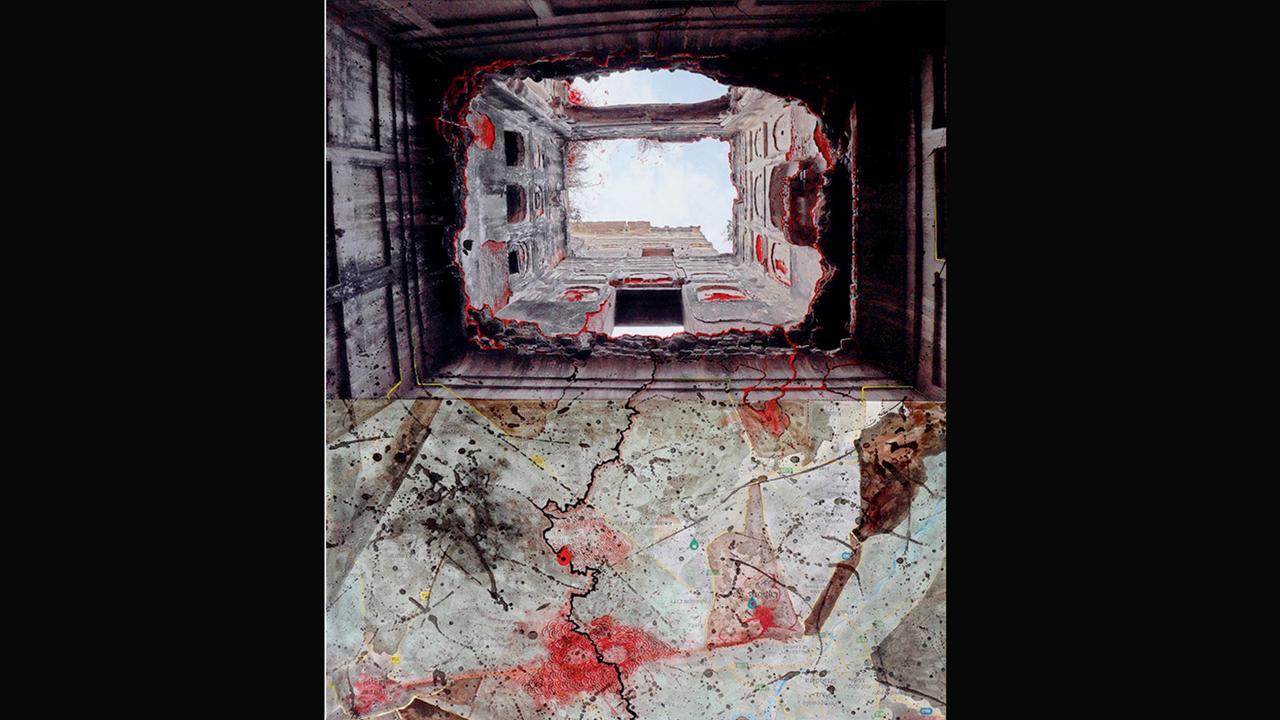

Maria’s photograph, nominated for the Sovereign Asian Art Prize 2021, shows a pre-partition haveli on the Indo-Pak border of Punjab province in Pakistan

Architect-photographer Maria Waseem grew up on the other side of Punjab. It wasn’t India, but had remnants of it, with a shared border—the presence of which her nani spent most of her life vexing about. “She had a lot of Hindu friends who moved to India after the Partition. That loss stayed with her forever. In the later years of her life, when she was afflicted by a mental health illness, she’d only talk about India. In those days [the 1980s], Punjab [province of Pakistan] would see Doordarshan air on its television network. I remember nani watching Chitrahaar and Mahabharat. For some reason, she was stuck in pre-Partition, and never came out of it,” says Lahore-based Maria ruefully, over a telephone call. Her husband, noted miniature painter and visual artist Waseem Ahmed, who has joined us on the call, and also has roots in India, shares the story of his family. “My nana and nani lived in Ajmer before the Partition. While nani loved Pakistan, my nana never reconciled with the loss. He had to leave everything, including his home and a secure job in the railways. He was so hurt, he never went back to India. But, I grew up listening to stories about Ajmer, and it felt like I knew the place by rote. I had created a blueprint in my mind. When I visited Ajmer for this first time in 2007, it felt like I had always lived there.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Although the couple admits to not having witnessed the scars of the Partition first-hand, living with these stories has seen them make sense of the pain and wounds that run deep. Their recent exhibition, Till Death Do Us Part at the Sanat Initiative in Karachi, explores the pre-partition architectural history and landscape of both countries, and the borders that divide them. While Maria’s photographs take us through abandoned structures, religious buildings, and the shared tracts of land, valleys and blue sky, Waseem interjects his painterly marks on these images, showing foliage, splashes, streaks, lines, cracks and walls, otherwise invisible to the naked eye.

A photograph of a mustard field on the border of Punjab, painted on with dry pigment colour by Waseem, to show a translucent curtain, with a line running past it. The image was part of the recent exhibition, Till Death Do Us Part, at the Sanat Initiative in Karachi

A photograph of a mustard field on the border of Punjab, painted on with dry pigment colour by Waseem, to show a translucent curtain, with a line running past it. The image was part of the recent exhibition, Till Death Do Us Part, at the Sanat Initiative in Karachi

Both Maria and Waseem are curious explorers; they’ve travelled the length and breadth of Pakistan, discovering vanishing architectural spaces that aren’t part of mainstream conversation in their home country. Maria’s interest began while she was still a student of architecture at the National College of Arts (NCA) in Lahore, two decades ago. “While deciding on the subject of my thesis, I came across an article in a fashion magazine about vastu shastra [texts on the traditional Indian system of architecture]. It immediately got my attention, and I decided to pursue it. Some of my professors tried to dissuade me, because they weren’t familiar with vastu. I then approached my external advisor Kamil Khan Mumtaz, who is a renowned architect here, and he encouraged me,” says Maria. Since she had access to few texts to supplement her research, Maria recalls having to fight with her parents to travel to Delhi to complete her thesis. “It’s then that I developed an interest in traditional architecture.” Later, while working as architectural researcher on a book on the famed pre-partition architect Bhai Ram Singh, whose noted works include the NCA (formerly known as Mayo School of Industrial Arts) and Lahore Museum in Lahore, Governor’s House in Simla and Durbar room in Osborne House, England, she developed an interest in photographing lesser-known structures like old residential buildings, gurdwaras, and Hindu temples, many abandoned since 1947, and in ruin. Waseem was also a student of NCA, and joined her on these trips.

Recently, one of Maria’s photographs, titled The Rupture, was nominated as one of the finalists for the Sovereign Asian Art Prize Hong Kong 2021. The structure in the image was that of a pre-partition haveli in Padhana village on the Indo-Pak border of Punjab province in Pakistan. It belonged to Sardar Jawala Singh, who commandeered the Sikh Army during the reign of Maharaja Ranjit Singh and was married to the eldest sister of Rani Jind Kaur (empress of Punjab). “During the Partition, the family refused to leave their lands and instead converted to Islam. They still live in the village,” says Maria. Parts of the structure, especially the ceilings, were destroyed in the 1965 Indo-Pak war. “I took a view of the ‘partitioned/ruptured sky’ through the broken ceiling and attached an image of map of that area where the border of India and Pakistan is visible merging with cracks of the structure.” The idea was to show how the cracks in walls and division lines of countries are not very different.

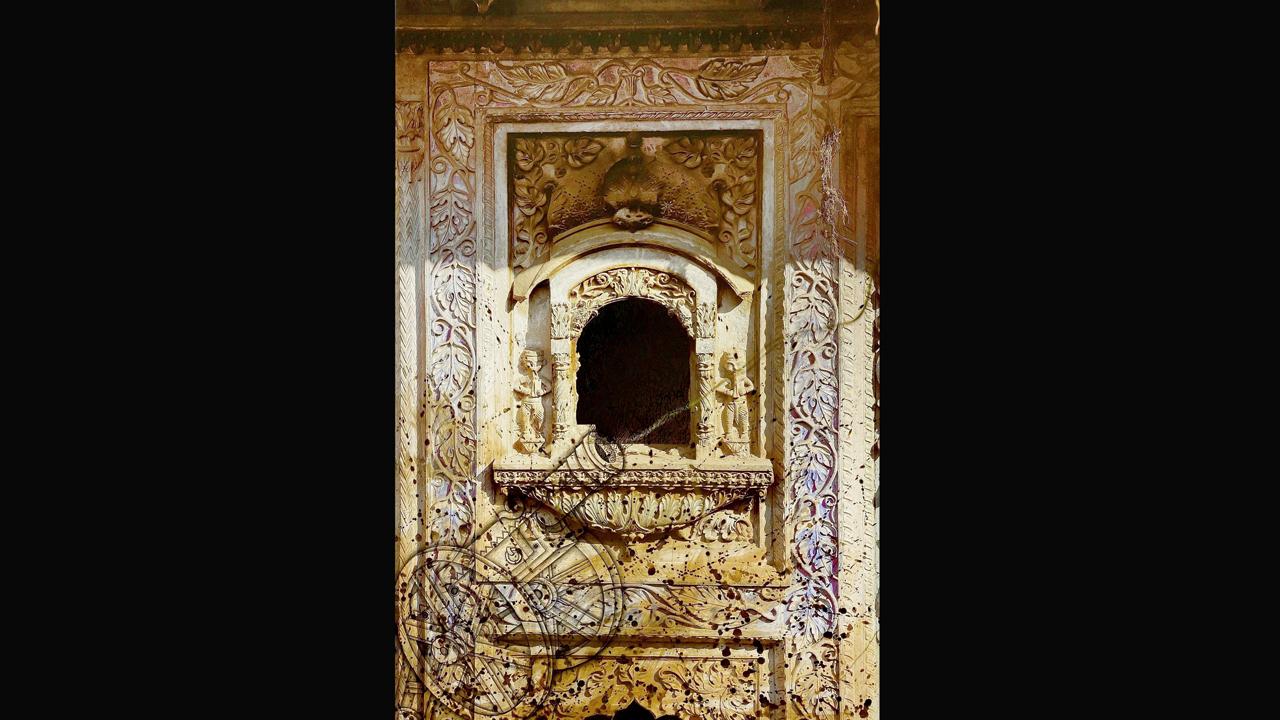

A photograph of a jali in Pranami Mandir in Punjab, Pakistan, on which Waseem has drawn a cannon, to reflect on how sometimes unintentionally or even forcefully, a structure loses its significance. “For instance, this is a Hindu temple, but is inhabited by Muslims,” says Waseem

A photograph of a jali in Pranami Mandir in Punjab, Pakistan, on which Waseem has drawn a cannon, to reflect on how sometimes unintentionally or even forcefully, a structure loses its significance. “For instance, this is a Hindu temple, but is inhabited by Muslims,” says Waseem

Waseem decided to develop this concept for the just-concluded exhibition. The duo collaborated and worked on 19 images that throw light on the indiscernible fault lines. “We wanted to express how we were feeling about what we had witnessed during our travels, through mediums that we best understood,” says Waseem, adding, “So, for instance, if there’s a dilapidated and abandoned building that Maria has photographed, I’ve shown foliage over it. I believe that nothing can really be destroyed, and something else takes its place. Plants usually come to occupy these spaces, giving them new life.”

There’s also the image of a mustard field, printed on archival paper, which has been painted on with dry pigment colour by Waseem, to show a translucent curtain, with a line running past it. “This image was taken on the border of Punjab. It’s the same soil and land that rolls into the other, but the borders are so tight that a slight misstep, and we could land into trouble,” says Maria. Another photograph shows Keran, Neelum Valley in Jammu and Kashmir. “The valley is part of India and Pakistan, and the river Neelum flows between. Here, it’s the river that represents the border,” adds Maria. “If you see it from far, you can’t make out where one land begins, and the other ends.” Waseem highlights these lines in black and red.

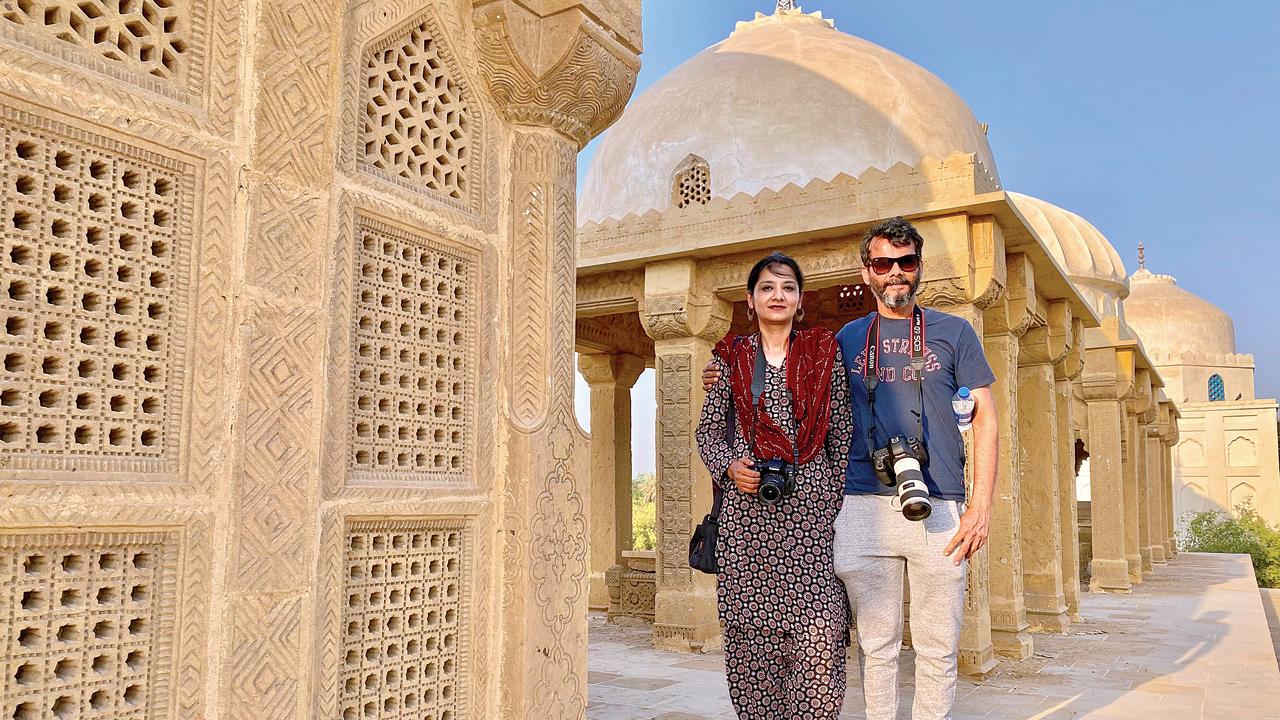

Architect and photographer Maria Waseem with husband Waseem Ahmed, a miniature painter and visual artist

Architect and photographer Maria Waseem with husband Waseem Ahmed, a miniature painter and visual artist

Maria, who updates her Twitter and Instagram feed with these discoveries, hopes she strikes a chord with the people of India. “Architecture is a silent storyteller, but these stories need to be seen and heard,” she feels. Some years ago, when she shared a picture of a crumbling temple in Sialkot on social media, it drew the attention of the authorities, who then began work on its protection. Sometimes, even locals do their bit, and unknowingly. “There’s this temple in Lahore’s Anarkali Bazaar called Bansidhar. An old woman who lives in this temple showed me a fresco of Lord Shiva, which she cleans every day. She asked me if I could get someone to preserve it. That moved me. This is not about religion. It’s about people, and their attachment to the past. There is still a lot of pain and these structures reflect it.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!