The portrayal of gay men in commercial cinema has gone from sissy stereotypes to bronzed specimens who are masculine without a trace of limp-wristedness

Running counter to the tyranny of recently reinstated Victorian-era laws, India’s (now illicit) gay underground continues to thrive.

ADVERTISEMENT

Jared Leto took it away with Dallas Buyers Club

The online dating scene is teeming as never before and perhaps so open and omniscient that it can no longer be considered outside the mainstream, unfettered instant access to its joys and ills being just a Google search and a few choice keywords away.

Sid Makkar in Straight, Ek Tedhi Medhi Love Story

The internet has enabled a whole generation of Indian gay men to interact, away from the squalour of dim back-alleys or the stench of men’s rooms, within new virtual systems erected specially, it would seem, for the barter and exchange of bodily fluids.

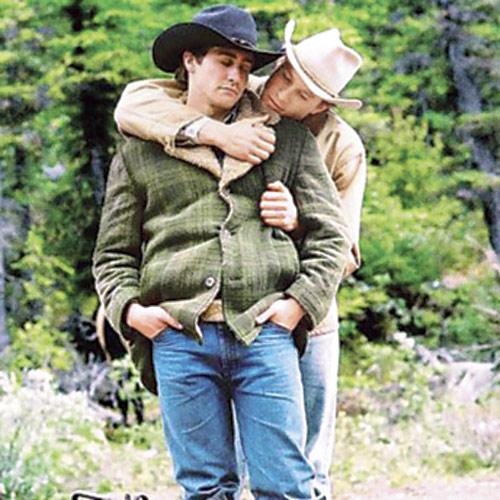

Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal in Brokeback Mountain

One such popular mobile app, Grindr, “sniffs” out men in the vicinity using GPRS coordinates for quick and snappy tech-enabled ‘one-hour stands’, so in many ways the spontaneity and randomness of public cruising hasn’t completely been obliterated.

Prithviraj Sukumaran

In the past, the shameful fumbling in local trains or public parks needed no names to be stated or wagers to be placed, but only the most superficial of attributes to present themselves in shrouded secrecy.

On a dating site, superficiality is still king, and goods for sale are propped up unabashedly with grainy thumbnails of the metrosexual man’s sculpted décolletage or taut derrière (whatever floats one’s boat) or indeed how his crown jewels fill up state-of-the-art skivvies because scoring big on the “manhood” stakes still counts for a lot.

Clued in

Several of these online ads come equipped with little 100-word (or more, for the erudite kind) descriptions which can sometimes be preciously intimate, where a man’s mind (or dare say, his feelings) is used as an object to appeal, rather than just body parts or bodily functions. It could be the terse articulation of bedroom tastes, or one’s handed-down-generations philosophy of life, or a penchant for para-sailing or orchid farming. The diversity is mind-boggling.

Taken as a whole, these epigrammatic nuggets certainly allow the attitudes of an entire gay populace, or at least a viable subset, towards a multitude of issues to bubble to the surface. More men seem clued in about who they are and what they want and how they want to go about it, unlike their bewildered predecessors, but despite this disarming self-sufficiency on display, there is still a murkier side that continues to characterise these worlds.

The spectre of entrapment looms large (the few incidents that hit the scandal pages are just the tip of an iceberg), married men lurch in the shadows still struggling to straddle two boats, good folk past the ripe old age of 35 are dismissed as “uncles, oldies or geriatrics” (less shelf life than even Bollywood heroines), but worse still is the skewed perspective of masculinity that remains the mainstay of the closet, an institution that perhaps owes its genesis to the all-encompassing patriarchy and its “men must be men” spiel.

Overcompensating

Due to centuries-old stereotyping, gay men have long been dismissed as effete, weak or impotent. The “sissies brigade” were objects of derision — good for a laugh, a few taunts, and the occasional lynching. As a result, gay men tend to overcompensate both in terms of embracing masculinity as some kind of immutable ideal, and in their own retrograde attitudes towards those who don’t conform to this Pyrrhic standard.

Taking the world of Grindr and its spin-offs as a useful microcosm, it is common to come across curt “Keep Away” signs directed at “femmes, trannies, aunties, sissies, hijdas, queens, fruits and faggots” — it is open season for cheap shots at effeminate gay men. Perhaps, for those who issue such restraining orders, there is the insecurity of being ousted by association, or the belief that the campness would rub off on them.

Or, considering how gay men have the whole whittling down of prospective suitors down to a fine art, they are creating their own parameters for desirability, as they’re quite entitled to. Whatever be the reason, the words remind us of the language of hate that bullies use in playgrounds or locker-rooms, and their ubiquity in avenues meant for romantic expression between men, that are proclaimed as safe spaces for the community, is disquieting if not outright homophobic.

Gender implication

The internalised hatred demonises not the gaze that makes an effete man an object of such ridicule, but the man himself. It is a self-loathing that rears its head in the bedroom as well.

The man who refuses to kiss because he is not a “fruit” (never mind the mid-afternoon sex soirée), or the man who believes that sexual agency only lies with the partner who penetrates, or the man happy to receive oral pleasure but unwilling to reciprocate.

Every quirk of behaviour seems to have a gender implication, and men, gay or bisexual or otherwise, try to align themselves along such rigid lines because that is what they feel makes them who they really are. Not the labels, but the construct.

The irony is that the battles of the movement have been fought by queer activists who have not allowed these didactic notions of masculinity to define who they are. While they are out sloganeering and fighting court battles, the other kind party in hyper-masculine environs with entry clauses that state, “Drags not allowed”.

No middle ground

The past year has seen a marked shift in the portrayal of gay men in commercial cinema. In place of the sissies have arrived bronzed specimens — from marquee names like Randeep Hooda and Saqib Saleem in the Karan Johar segment of Bombay Talkies, to Prithviraj Sukumaran in his Malayalam potboiler, Mumbai Police — who are all masculine without a trace of queer.

If you scratch the surface, you will find a man who has killed his best friend to preclude a public outing, or a man seducing the husband of the woman who took him under her fold, or a gay man trapped in a marriage that is a lie perpetrated by himself.

The film-makers may have created these disturbing (and almost pathologised) characterisations in order to react to the closed society in which we live, that maims gay men and makes them less whole. What is surprising, is that these roles have been given a clean chit by gay audiences and embraced as fully representative, ostensibly because none of these men were effeminate.

So, it would appear that the proverbial chip on the shoulder has always been celluloid limp-wristedness, the message being, “Portray us as killers, liars and cads, but not as queens.” The same audiences would find it hard-pressed to display similar enthusiasm for Jared Leto’s lacerating turn in Dallas Buyers Club, as a transsexual man dying of AIDS.

Here we have someone who has struggled to embrace his feminine side, but even in his drug-induced torpor, there is a striking humanity that raises him outside the realm of being merely a cipher for a community — a person in his own right who only really wants to look beautiful when he dies.

Early in March, Leto won an Oscar at a ceremony presided over by arguably the world’s most famous lesbian, Ellen DeGeneres. It’s hard to think that our films could ever have such irrevocably real people inhabit them. The middle ground that gay men (and indeed all men) occupy is lost.

This is the space between the screechiness of a tasselled Bobby Darling and the bolstered masculinity of a uniformed Prithvi — although here is an actor, who was completely in his element as a pinup catering to a female (and by extension, the gay male) gaze in Aiyya, made by playwright Sachin Kundalkar, who has operated often within the queer idiom.

Personal struggle

What puts things in perspective is the kind of personal struggle that was wonderfully staged at the International Theatre Festival of Kerala earlier this year by the Czech performer, Mirenka Cechova. Her solo performance, S/He is Nancy Joe, was a poignant take on the transitioning of a female-to-male transsexual, Joe.

There are illusory moments in the piece — Joe headed to the ladies’ room, but drawn inexorably to the men’s loo, as scores of little cherub-like penises swarm over him, their wings fluttering to the steady trickle of urine being passed from the ‘standing-up position’ so easily summoned by men.

Scissors loom large, as the spectre of corrective surgery raises itself. The sapping hormonal therapy (with its unending pill cycles) that accompanies surgery is illustrated to touching effect. At one point the backdrop is splattered with paint the peeling off of dried paint evocative of the intense moulting Joe has to undergo.

A red frock becomes the motif of oppression. Here, unlike the baggage carried by gay men, masculinity is stripped away from boorishness and swagger and privilege, being instead the underlying motivation in the quest of simply becoming a man, just that much and nothing more.

The writer is a playwright who runs the theatre appreciation website, Stage Impressions, and frequently writes on queer issues

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!